Yeah, um, actually he was a Consitutional law professor at the University of Chicago for like twelve years.

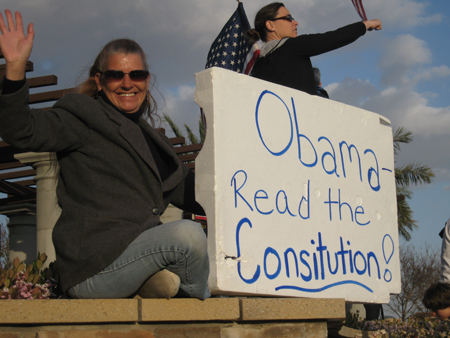

I’m not saying that one political position in America is currently smarter than the other, but the Senate health care reform package involves death panels, the President of the United States is not an American citizen, and the swine flu vaccine might be a trick. Also, this lady. When high school graduate Glenn Beck claims that Nelson Rockefeller was a communist because of a mural he commissioned from Diego Rivera—a mural whose depiction of Lenin angered Rockefeller so much that it touched off the century’s greatest controversy in public art—it’s tempting to conclude that his position is influenced by, well, ignorance. As we all know, “ignorant” is a polite way of saying another word that we have been trained never, ever to use in the context of responsible political debate. You can’t get anything done by disparaging people’s intelligence. To do so is, at best, to commit the ad hominem fallacy, and at worst to provide your opponent with a weapon that they will use against you later. We don’t argue about who’s smarter in America. Anyone who does winds up looking stupid.

Still, in our moments of great frustration—when, say, someone holds up a picture of the nation’s first black President dressed as Hitler—we wonder. It’s a truism these days that America’s college campuses are a hotbed of liberalism, particularly among the professoriat. What do college professors have in common? It isn’t that they reject Darwin’s theory of species differentiation through natural selection in favor of something they leaned in Sunday school. If you ask your orthopedic surgeon, your favorite math teacher, the guy who screwed up your roofing contract and Steven Hawking to decide whether gay dudes can get married, the vote will probably be three to one. Smarter people—or at least better-educated people—tend to be more liberal. It’s a completely unprovable fact.

Or it was until early this year, when Lazar Stankov published “Conservatism and Cognitive Ability” in the peer-reviewd scientific journal Intelligence. I subscribe to Good Looks and Bullshit, so I wasn’t aware of Stankov’s work until I read Jason Richwine’s partial refutation of it in The American, which is the journal of conservative think tank The American Enterprise Institute. If you have time to read only one peer-reviewd scientific study today, read “Conservatism and Cognitive Ability,” but if you don’t you can probably just read Richwine.*  Stankov’s essential contention is that, lo and behold, conservative political viewpoints correlate inversely with intelligence. It’s important to note that he defines “conservative” in its historical incarnation: Stankov’s conservative is a person who “attaches particular importance to the respect of tradition, humility, devoutness and moderation; as well as to obedience, self-discipline and politeness, social order, family, and national security; and has a sense of belonging to and a pride in a group with which he or she identifies. A Conservative person also subscribes to conventional religious beliefs and accepts the mystical, including paranormal, experiences.” Stankov is describing a social conservative, not the kind of free-market ideologues who think Social Security is morally wrong. He’s also basing his research on a group of students, half of whom come from foreign countries, so the applicability of his conclusions to American politics is debatable. Still, Stankov’s kind of conservative—religious, hawkish, family-focused and proud to be something or other—increasingly forms the backbone of the Republican Party. At least according to one scientific study, such people are statistically dumber.

Stankov’s essential contention is that, lo and behold, conservative political viewpoints correlate inversely with intelligence. It’s important to note that he defines “conservative” in its historical incarnation: Stankov’s conservative is a person who “attaches particular importance to the respect of tradition, humility, devoutness and moderation; as well as to obedience, self-discipline and politeness, social order, family, and national security; and has a sense of belonging to and a pride in a group with which he or she identifies. A Conservative person also subscribes to conventional religious beliefs and accepts the mystical, including paranormal, experiences.” Stankov is describing a social conservative, not the kind of free-market ideologues who think Social Security is morally wrong. He’s also basing his research on a group of students, half of whom come from foreign countries, so the applicability of his conclusions to American politics is debatable. Still, Stankov’s kind of conservative—religious, hawkish, family-focused and proud to be something or other—increasingly forms the backbone of the Republican Party. At least according to one scientific study, such people are statistically dumber.

The implications of such a discovery are, once they stop being fun, fairly troubling. Representative democracy is predicated on, if not the assumption, at least the agreement that all advocates of whatever position are equally valuable, and therefore to be removed from consideration in political debate. Once you start comparing people instead of ideas, you have an aristocracy. What are we to do with evidence that one end of the ideological spectrum is consistently favored by dumber people? Richwine’s answer, in part, is to point out that smarter people do not always make better decisions. That’s true on a logical level, but it’s hardly comforting. If we’re not talking about an overall pattern of poor decision-making and the inability to fully grasp complex situations and ideas, what exactly do we mean when we say dumb? As one of my former clients famously remarked, “He’s very smart—he just has a hard time acquiring new concepts, and applying the ones he’s already learned.” Once we start denying that being smart has something to do with being right, we’re just talking about whether or not we like you.

Richwine’s second point—that being politically liberal entails a certain amount of iconoclasm, and to be an iconoclast requires the intelligence that pushes one toward critical thinking—is more convincing. Liberals, particularly in Stankov’s construction, are people who have come to question the value system in which they were raised. To do so requires a certain degree of intelligence, but being intelligent doesn’t require being liberal. Richwine argues that political progressivism is like the NBA: almost everyone playing pro basketball is tall, but that doesn’t mean the majority of tall people play pro basketball. Again, his argument is logically sound, but it becomes less compelling when applied to the practical world of American politics. I’m going to host a lightbulb-changing and high shelf-reaching contest at my apartment—do you want to be on the team of people who love to play basketball, or the team of people who hate it?

The intelligence question is especially vexing given the tenor of contemporary politics. When Sarah Palin speaks of “elitists” versus “real America” or Glenn Beck makes a cardinal virtue of “common sense,” it’s not hard to understand what they’re talking about. If the United States isn’t an anti-intellectual country—Bush vs. Gore 2000, Bush vs. Kerry 2004, Adlai Stevenson lifetime—the GOP has certainly made itself an anti-intellectual party. The proper response to being called an elitist should probably be to say, “And you’re not?” and sip archly from one’s old-fashioned. Instead, progressives—particularly progressive politicians—have trained themselves to downplay their academic and policy credentials, and adopt the just-folks attitude the American people apparently embrace. Where do you think Barack Obama got that vaguely southern accent—as an undergrad at Columbia University or as a lecturer at Chicago Law? Come to think of it, where did George W. Bush?

Both positions—Republicans’ anti-intellectual posturing and Democrats’ ersatz folksiness—are symptomatic of a political class that thinks very little of its constituents. Richwine, in perhaps the most perceptive statement of his entire article, points out that “It is nearly impossible to rise to the top of the American political scene without some real smarts. Party leaders are rarely geniuses, but it is almost inconceivable that they could have below average IQs.” When the unstated assumption of both parties is that a candidate who seems too smart can’t get elected, what does it say about us? Every time Sarah Palin said “gosh” in a nationally televised vice presidential debate, it was a pronouncement on our intelligence. The most interesting implication of Stankov’s study is not that liberals, on the whole, tend to be more intelligent than conservatives. It’s that no American Democrat in his right mind would ever bring that up.

“I’m not a doctor, but I play one on tv.”

“I grew up in Kennebunkport, but I play a cowboy at election time.”

Rush Limbaugh may be surrounded by and cultivate the fealty of “dittoheads”; but he is a

broadcast genius, despite having come from Cape Girardeau, Mo.

If progressives are people who look forward, social conservatives are people who look at the uneducated and wonder how they can exploit them. It remains to be seen, over time, which group is smarter.

Great essay today.