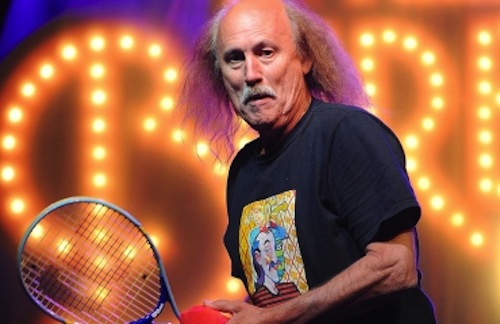

If I asked you what you thought of the prop comedian Gallagher, best known for making audiences sit through an hour of visual puns before his famous sledge-o-matic routine, you would probably say something mean. When I was ten, I loved the sledge-o-matic. I distinctly remember walking more than a mile to the video store to rent Gallagher videos with my brother. Twenty-five years later, that video store is a Subway and I am not laughing uproariously at the gag, “You want that cheeseburger to go? [Crushes cheeseburger with mallet.] It’s gone!” Yet Gallagher is doing the exact same thing. There he is in the photo above, making some sort of racket joke and wearing a t-shirt with a picture of himself on it. He is clearly an object of derision. Also, he just emerged from a medically-induced coma after his second heart attack. Now who’s an asshole?

In the same way that the sledgehammer turned out to be the missing ingredient of young Leo Anthony Gallagher’s standup act sometime in the late seventies, the key element in his late career turns out to be impending death. Here the Daily News bears quoting at length:

“Surprise, I’m still here!” the comedian, whose full name is Leo Anthony Gallagher, told a TMZ cameraman as he left the Lewiston, Tex., hospital Wednesday afternoon. “But in Texas, you get a deal: You get the heart transplant and the hair transplant,” he deadpanned, before pulling up his umbrella and showing off a piece of artificial grass he had stuck to the top of his head.

Picture Gallagher trying to focus his eyes as he emerges from a coma, lying for probably days in that hospital room and remembering his loved ones, his childhood in Texas, suing his brother, all of the things that make a life. Okay, he thinks, how can I make this funny? Then he calls his distraught family into the room and tells them to get a piece of astroturf and some glue.

Somewhere in there is the essence of tragedy. You have to dig through a lot of stuff to find it, though. The case of Gallagher is an instructive one, since he continues to do the same thing at all points in his life. In 1982, he is wearing a hat with a handle on it and smashing food on Showtime. In 2011, he collapsed on stage doing the sledge-o-matic in Minnesota. Gallagher’s act therefore serves as a sort of consistent function in the question of how we feel about him. The independent variable is how close he is to death.

When he was thirty or forty, his insistence on working the same gimmick night after night for the small subset of people who found it hilarious made him a stupid hack. This phenomenon was intensified by his public disdain for more successful comedians he considered less talented, including Robin Williams and David Letterman. It was totally okay to hate Gallagher, because he was making money doing bad work while simultaneously criticizing better comedians, along with “China people and queers.” When he is walking out of the hospital, however, the same hackery takes on a strange poignancy.

There’s an obvious reason for that: you should pity people who are about to die. Yet Gallagher, who in interviews and his general public persona strikes one as a person especially likely to pity himself, does not play the sympathy card at all. He just makes another idiotic ploy for cheap laughs. It is impossible to hate Gallagher in that moment. His desperate attempts to get attention by any means available—so dumb that they led him to disdain the people who rewarded them, so craven when he was healthy—become brave when he is going to die.

I submit that this phenomenon reveals a fallacy in our thinking. The fallacy does not lie in sympathizing with Gallagher now, however, but in deriding him when he was younger. We are all going to die. That doesn’t make it any funnier to stick grass to our heads, nor does it make it more dignified. But it does make it forgivable.

Gallagher is a comedian who has been lambasted for hitting on something that worked and doing it for the rest of his life. From a comedy standpoint, that is unforgivable, but from a human standpoint it is oddly brave. At least he is doing something, right? He could have just slowly made his way out of the hospital and lowered himself into the car to go home and cry with his family. Instead, he took the opportunity to work in one more gag. There is dignity in doing comedy in the face of death, even though it is terrible comedy, even though you are scared. In his obstinate, thirty-year sameness, Gallagher just got scared way before the rest of us.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AgPMDuEciWw

Did Dave Chapelle ever return to comedy? Maybe as ‘Black Gallagher’ he was enlightened to the true comedic genius of smashing food with a sledgehammer, which only he and the real Gallagher ever truly understood. Gallagher, upon discovering the sledgehammer bit is the final plateau of comedic enterprise, simply decided the best course was to continue doing it as much as possible until he dies. ‘Black Gallagher’, however, saw all future comedic effort as futile, and retired.

“We are all going to die. That doesn’t make it any funnier to stick grass to our heads, nor does it make it more dignified. But it does make it forgivable.”

Loved this, Dan.