Now that school is starting up again, it’s time for children across America to return to claiming to read books. Of course, it’s vitally important that no person—child or adult—read a book for real, lest they become a nerd. Yet knowing things continues to have value. The trick is to get other people to read books and then explain the good parts to you. In this way did I learn an amazing fact from Slate’s Osita Nwanevu via Twitter, about the origins of the word “kidnap.” Nwanevu is reading The American Slave Coast by Ned and Constance Sublette, from which he excerpts this passage:

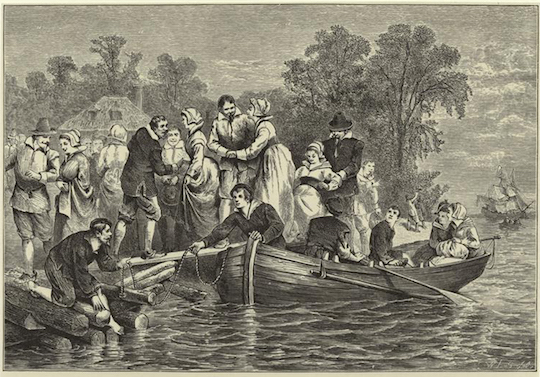

When the new “partners” of the Virginia Company arrived in America, they found to their dismay that they were conscripts, coerced into gang labor under martial law. Everything they produced was to belong to the company, so they had no incentive to work. Half or more of them died shortly after arrival. As word got out that Virginia was a death trap, agents, popularly known as “spirits,” went combing the street for potential indentured servants for the colony—a process that included abducting children, bringing the phrase “spirited away” into popular usage, as well as the word “kidnap.”

Now there’s a robust argument for privatization. Never forget that the United States began as a for-profit venture, and that for the first couple of centuries, more Americans were descended from abductees than from yeoman farmers. Also, the period the Sublettes describe roughly coincided with the writing of Shakespeare’s last plays.

If you want to understand early American history, the thing to remember is that it was the English Renaissance without the learning. The urban poor who composed the bulk of early colonial immigration were not much more than medieval. Particularly in the Chesapeake Bay area, where the Company emphasized profit above all else, they were woefully unsuited to life in a rural environment. The first rounds of settlers failed to plant crops or otherwise provide for the coming winter, in many cases just wandering off into the woods to search for gold.

In Jamestown, the death rate during the winter of 1607—known as the “starving time”—reached 68 percent. Better planning and a continual influx of willing immigrants, abducted English, European servants and African slaves kept the Chesapeake Bay colonies going for the next three decades, but the mortality rate hovered around 28 percent. Virginia was an investment for the Company and an abattoir for almost everyone else. Even as the introduction of tobacco farming gave the colony a sustainable economy and, eventually, a modicum of decent living, the distinction between rich and poor shaped everything.

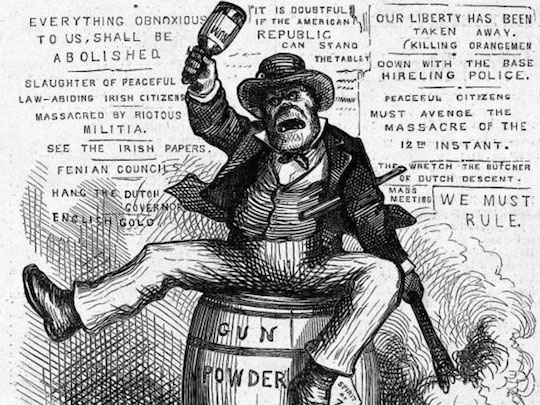

Consider Bacon’s Rebellion. By 1676, Jamestown had a robust tobacco industry that continually moved settlement west. Tobacco quickly depletes the soil, and this depletion combined with increasing land prices near the coast to push newly freed members of Virginia’s growing servant class into Indian territory. Westward expansion led to conflict with the Doeg, causing poor planters along the frontier to complain that governor William Berkeley wasn’t doing enough to protect them. Led by Berkeley’s rival Nathaniel Bacon, several hundred of these frontiersmen took up arms against the colonial government, driving Berkeley from Jamestown and burning the capitol.

Historians cite Bacon’s Rebellion as a turning point in America’s development as a slave society. Realizing that their reliance on indentured servants kept renewing the class of disenfranchised whites, the wealthy landowners of Chesapeake Bay turned to slaves, who offered the same benefits but never had to be freed. The creation of a new caste of Virginian below the white indentured servant also replaced class conflict with race conflict. Poor farmers and laborers who saw the governing class of Virginia as their enemies now saw them as their fellow whites. The shift from indentured servitude to slave labor was a deliberate effort by the ruling class of Chesapeake Bay to reduce political instability.

Anyway, the colonists came to America looking for freedom, which didn’t exist in England, and were helped by friendly Indians, who definitely taught them to plant crops and love nature instead of groping for gold in the woods until they cannibalized one another to survive. The middle-school version of colonial history is not accurate, but it’s easy to remember. The other, more complete version is useful to remember when you hear some Tea Party type appeal to constitutional values and the spirit of early American “patriots,” whose loyalty to country more strongly resembled a psychotic commitment to profit during for the first couple centuries. The old way worked, in the sense that here we are today, but it was not anything a modern person would call good. The colonies we imagine we remember are mostly an Eden: useful as a metaphor for our failure to live up to our present ideals, but not something that actually existed.