Patrick Young, Esq. is one of several to report that a high school student has disproven University of Illinois professor’s Richard Jensen’s claim that signs reading “no Irish need apply” were a historical myth. Originally published in the Journal of Social History in December 2002, Jensen’s “‘No Irish Need Apply’: A Myth of Victimization” argues that the signs forbidding employment to Irish immigrants in the 19th century were “an enhancement of political solidarity against a hostile Other; and a way to insulate a preindustrial non-individualistic group-oriented work culture from the individualism rampant in American culture.” That’s kind of a bigoted thesis, bro. Unfortunately, Rebecca Fried’s article—which is extremely commendable and impressive for a high school student—doesn’t seem to disprove it.

I say “seem” because I am not paying $39.99 to access the article for one day, as the Journal of Social History suggests. Way to erect a barrier to non-institutional scholarship, Oxford. Because I have not read Fried’s article, you should probably disregard everything I say in the rest of this post. People who have not read the primary sources do not get to participate in discussion. Still, at the risk of tarnishing Combat! blog’s academic reputation, I’m going to engage with Young’s secondary reading.

Young writes that Fried “proved Jensen wrong” by finding numerous examples of want ads that specify “no Irish need apply.” In noting a few from the Brooklyn Eagle, he even snarkily chastises Jensen, saying “I guess Professor Jensen did not look through Walt Whitman’s old newspaper.” But it appears that Jensen did. In paragraph three of “No Irish Need Apply,” he writes:

Apart from want ads for personal household workers, the NINA slogan has not turned up in the newspapers. The myth focuses on public NINA signs which deliberately marginalized and humiliated Irish male job applicants.

Again, Fried’s research is awesome, and she turned up many more ads for household workers specifying NINA than the “few” Jensen concedes. But he specifically exempts want ads for domestics from his claim, and want ads for domestics seem to be the counterexamples Fried found.

So the story that a high school student disproved a history professor in the same journal where he denied an iconic expression of anti-Irish prejudice is, while immensely pleasing, probably not right. It’s fantastic and interesting that Fried did original research to dispute the problematic claims of a historian. But I am also interested in why this story is so popular.

Virtually every white person in America claims some Irish ancestry. I submit that historical prejudice against the Irish is important to white people, because it vaguely feels like it takes the edge off what white people did to everyone else. Every nonwhite ethnic group has been persecuted at some point in American history, with the possible exception of aboriginal Australians. To argue that the Irish were persecuted, too, implies that discrimination is a bad thing that happens to people, rather than a bad thing white people do to everyone else.

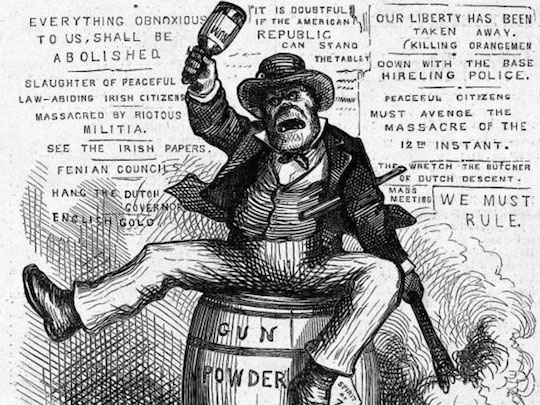

That’s probably true, but while Irish people were the subject of mean cartoons, black people and Indians were being systematically exterminated. Anti-Irish bigotry is virtually absent from the 21st-century United States, whereas prejudice against other, nonwhite ethnic groups remains very real. At the risk of comparing sufferings, the period when it sucked to be Irish in the United States was ephemeral relative to, say, 200 years of slavery.

For more on the Irish diaspora in America, check out Noel Ignatiev’s How the Irish Became White. For more on how the white became Irish, talk to any drunk on St. Patrick’s Day. While you’re “listening,” consider how Martin Luther King Day is not a boozy party in the streets, and what that might say about the role ethnicity plays in different American lives.

For white people, Irish ethnicity is a tri-cornered hat: a fun way to engage with history that can be taken off when the time for screwing around is over. Historical prejudice is different for other ethnic groups. As problematic as is Jensen’s claim that “the use of systematic violence to achieve Irish communal goals might be considered a ‘premodern’ trait”—imagine a historian writing that about Geronimo—it’s nothing compared to, say, the ongoing belief that black men are likely to possess supernatural powers. During the 19th century, Irish immigrants were the victims of widespread prejudice. The difference between the Irish and virtually every other nonwhite ethnic group is that eventually, that prejudice stopped.

My posts have been eaten two days in a row!