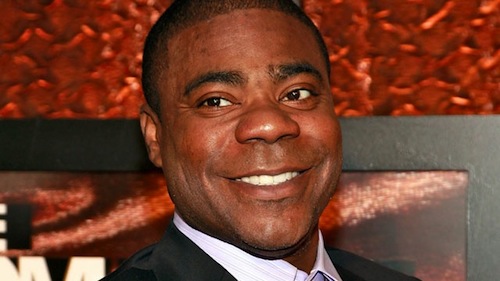

I’m a big fan of Tracy Morgan, so I was chagrined to hear that he said a bunch of crazy homophobic stuff onstage in Tennessee last week. Now Tracy Morgan is bad, at least for a couple of months or until some other comedian does three minutes about loving poon and stabbing his hypothetical gay son. I have not seen video of the act in question, so I can’t say whether it was funny. Initial reports suggest it wasn’t, but who knows? Morgan is not exactly a comedian who works well in precis. The moral reprehensibility, on the other hand, is visible from a distance. While Funny is ephemeral and contingent, Immoral—along with its mumbling cousin, Wrong—is easy to discern. This presents a problem, however. Had what Morgan said been hilarious—like when he threatened to get various Chicago citizens pregnant in 2007—everything would have been cool, or at least arguably cool. It would appear, as Ann Power argued in 1997, that aesthetic standards can either damn or redeem transgressive art, whereas morality is unequipped to make such distinctions. As a result, moral standards are invariably an instrument of condemnation.

First, it should be noted that the 1997 examples of offensive popular art that Powers invokes are totally hilarious. The article addresses pre-Oscar Trent Reznor, pre-Law & Order Ice-T, pre-America Online commercial Snoop, and several other people whom American society no longer considers threatening. Ice Cube*![]() is not mentioned, but he’s pretty much all that’s missing. The point is not that these one-time bugbears are no longer even remotely transgressive, though, or even that they were ever good. The point is that, according to Powers, the purpose of Nasty Art is not to help society by addressing taboo issues or giving voice to the oppressed. The purpose of Nasty Art is to be nasty.

is not mentioned, but he’s pretty much all that’s missing. The point is not that these one-time bugbears are no longer even remotely transgressive, though, or even that they were ever good. The point is that, according to Powers, the purpose of Nasty Art is not to help society by addressing taboo issues or giving voice to the oppressed. The purpose of Nasty Art is to be nasty.

“I’m not talking about recovered memory, hippie liberation, or good old catharsis,” Powers says, after describing her fascination with an underage lesbian fisting comic. “Just the compelling realization that, past the edge of whatever I don’t want to think about, there’s more.” Here is the argument for transgressive art as experience rather than instrument. It’s also the argument that the moral approach—which address content separate from context to focus on the art’s likely effect on its audience—does not consider.

The problem with the moral rubric is that it does not distinguish between good transgressive art and bad. At best, it argues for free speech as a positive good, but even there it cannot distinguish between the freedom of Lolita and that of Barely Legal. The problem with the moral position is that it collapses Tracy Morgan trying to dig himself out of a silence with ever-more shocking comments about his imaginary son and, say, Eddie Murphy arguing against property rights for divorcées. From an instrumental standpoint, they’re the same thing. One is much funnier than the other, but that hardly matters: being gay is not a choice and women are entitled to half of jointly-owned assets in a divorce.

The problem, of course, is that one of these works of art is worthwhile and the other one probably sucks. “Not all art that claims to be transgressive is worth caring about,” Powers writes. “But you can’t tell the bullshit from the real by setting moral standards. You have to set artistic ones.” Tracy Morgan ranting about how he doesn’t get gay dudes is likely not useful transgressive art, because it isn’t enjoyable. Inglorious Basterds, on the other hand, is great. It’s not like beating a man to death with a baseball bat is cool because he’s a Nazi, which is about the only explanation the moral argument is equipped to furnish. It’s that Inglorious Basterds is good art—that is, affecting art. It pushes us into an experiential space where the transgression of moral boundaries becomes visceral, sensory. We are forced not just to recognize the boundary, but to cross it.

In the same way that one can travel to Canada without advocating the dissolution of the northern border of the United States, one can enjoy Nasty Art without wanting to erase the line between nasty and okay. First, though, you have to enjoy it. This question—was it cool?—is the one that the moral argument ignores. This omission invariably leads to the phrase I find most infuriating in this context: that was uncalled-for. There’s no reason for Tracy to have said that stuff in Nashville. There’s also no reason for Nabokov to have written Lolita, or for Ghostface to have recorded “Shakey Dog”—no moral one, at least. The moral position is well-equipped to identify the consequences of art, but it has no tools for measuring experience. Maybe that’s why it invariably decides in favor of silence.

I haven’t watched Inglorious Basterds in its entirety (I got bored) but I’m guessing there wasn’t anything you really found that objectionable (skull-bashing? please!). Personally, I, at least, would find that maybe gross but not wrong. Anyway, good liberals tend to think depictions of sex are great and moral, and good dramatists know we often need to visualize dramatic conflict (violence). So what I’m saying is, some of us don’t really have that much of a moral issue with the things that others tend to object to.

But we should all still maintain an absolute moral sense about the contents of our art/entertainment, regardless of whether or not it is good art. If you stab an audience member in the hand, or sexually assault someone in your performance art piece, or subtly incite people to homophobia or genocide or just to inert brain-dead complacency, it is an absolute moral wrong, whether your art is good or bad.