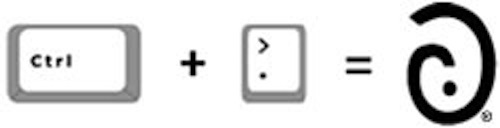

The sarc mark, which indicates sarcasm and itself contains the registered trademark mark. This picture will irreparably damage your eyes.

The good people at the Michigan-based company Sarcasm, Inc. have invented something called the “sarc mark,” a punctuation mark that indicates sarcasm in written correspondence. For only $1.99, you can download the sarc mark and use it in your emails, text messages and Facebook status updates, so that people will finally stop thinking you’re so glad your flight got delayed. The problem of conveying irony in text can be especially vexing, as anyone whose girlfriend has an attachment disorder will attest. We have a tendency, when we are hastily tapping out half-funny text messages at red lights, to simply transcribe what we would say in speech, and our sarcastic speech is augmented by tone of voice, rolling eyes, the jerkoff motion and other flourishes that keyboards don’t have. That being said, a punctuation mark that indicates sarcasm is an awful idea. At best, it will point out at the end of each sentence what dicks we all are. At worst, it will gradually destroy our ability to think. Normally I’m happy to pay $1.99 for that service (episode of Jersey Shore on iTunes) but dammit, some things are sacred, and the western tradition of written irony is one of them.

Before we get any further with this, let me say that if the sarc mark makes no other contribution to society, it has at least quickly exposed what hacks internet writers are. Virtually every article addressing the sarc mark begins the same way, by asserting that it’s a great idea, that Sarcasm, Inc. is a well-known, respectable company, and that before the sarc mark there was never any way to tell if people were being ironic or not. Do you see what they did there? That’s the kind of genius idea you can only come up with by very briefly trying to think of an idea, executed with a subtlety born of deep fear for your reader’s intelligence. That fear, of course, is precisely what led someone to come up with the sarc mark in the first place, and it’s one of the few things that makes sarcasm fun. When you say that the new Black Eyed Peas album is terrific, it seems possible that some dumb bastard somewhere might think you actually mean it. It’s the same sort of cheap thrill you get from a Dead Kennedys t-shirt or a Harley Davidson. Even though pretty much everyone understands and remains completely unthreatened by sarcasm, you can still indulge the fantasy that you are rebelling a little—that you are in some small way freaking out the squares.

That’s probably why sarcasm is so popular with dumb people as a means of simulating wit. Whether you’re writing a children’s movie or in line at the DMV, saying “Well, this is just great,” is a good way to convey your recognition that a joke probably belongs there, without incurring the obligation to actually come up with one. Oscar Wilde—whose last words were “Either these curtains go, or I do”—is generally credited with pointing out that sarcasm is the lowest form of wit. As usual, “lowest” means “most widespread.” In contemporary America, sarcasm has become the Crocs of rhetoric—everywhere, and always near someone you wish you couldn’t see. Those of you who are so ironically lonely that you ironically begin reading Craigslist personal ads know that “sarcastic” has become shorthand for “ostensibly funny, but mainly just unpleasant.” The popularity of sarcasm as a tool of the angry-yet-boring—who comprise, nowadays, like sixty percent of the population—has resulted in significant definition creep. “Sarcastic,” like “literally” and “ironic,” has come to indicate a mood more than an actual thing, as evidenced by this commercial for the sarc mark, which suggests that the people at Sarcasm, Inc. are disturbingly unsure about what the name of their company might mean:

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WlwCCWGYOGg&feature=player_embedded

When Sarc Mark Man says, “Come on, one more lap, tubby,” to a female jogger—who, by the way, does not seem to be running around anything circular—and then stamps her on the ass with the sarc mark, we are forced to assume that sarcasm is now any form of A) cruelty or B) sexual harassment. It isn’t. Sarcasm is an especially straightforward type of irony, in which the figurative meaning of your statement is the diametric opposite of its literal meaning. “I’m not bored at all,” is a sarcastic thing to say at the poetry reading. “Nice sweater, pussy,” is just regular mean. If we take the second, increasingly popular sense of the term as the actual definition of “sarcastic,” as the people at Sarcasm, Inc. evidently do, then the stated purpose of the sarc mark is patently dishonest. “Never again be misunderstood!” says the sarc mark homepage. “Never again waste a good sarcastic line on someone who doesn’t get it!” The problem, when you run up to a jogging woman and call her tubby, is not that you’ve been misunderstood; it’s that you’ve been understood perfectly well, and you’re about to be held responsible for your actions. The real purpose of the sarc mark seems to be to somehow excuse yourself for being a jerk, the way you say “Sorry—I’m really tired,” when you notice that your spouse is about to cry. We really settled for each other, didn’t we, honey? Sarc mark!

The use of the sarc mark in this context—as an excuse for some combination of resentment and laziness—threatens to rob us of sarcasm’s few pleasures. Consider Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal,” perhaps the greatest work of sustained sarcasm in western literature. It is the rare high school English student who reads it and then writes his three-page essay passionately arguing against the consumption of Irish children as a means of population control, but when he comes along, what a wonderful gift he is. Employing sarcasm with no clear indication that you are doing so requires a certain amount of confidence—that your sentences are well-constructed, that your ideas are of evident value, that your reputation as a person who is not a well-known idiot is still intact. It is the tiny thrill of closing your refrigerator with a spinning hook kick: most of the time it will work, and a very small percentage of the time you will knock your teeth out on the counter and fall into a pile of broken salad dressing bottles. That’s what makes it fun.

Of course, the other thing that makes sarcasm fun is the social contract—the assumption that your reader is smart enough to get it, too. It is the lack of faith in this contract that makes the sarc mark so sadly ironic; it seems to have been invented by a bunch of people too stupid to construct sarcasm, for the express purpose of dealing with people who are too stupid to understand it. With any luck it will become insanely popular, and Facebook feeds and text messages and Fox News crawls will be festooned with sarc marks. When that happens, the sarc mark will finally serve its intended purpose and replace the true function of sarcasm, by providing a handy way to quickly identify stupid people. On that fine day, the rest of us can return to speaking in earnest, and leave sarcasm to the entrepreneurs.

“A sarcasm detector. That’s a REALLY useful invention!” — Comic Book Guy.

I laughed out loud at every paragraph, beginning of course with the girlfriend with an attachment disorder. Winky smiley face for you, bud.

It’s interesting how you detest the idiocy of blunt sarcasm while enjoying the guileless, dim student who argues against Swift. I have no idea what that could mean.

Sarxmark is the best idea ever.

Great entry. Really funny and great investigation of how satire should work.

The description of Swift’s work as sustained sarcasm strikes me as wrong, somehow, though. Is satire just extended sarcasm? Certainly sarcasm is usually a shorter, one-off thing. But satire also has deeper parodic and critical elements, I think.