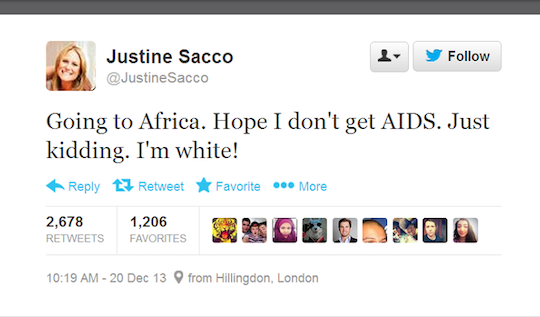

You should follow Willy Staley on Twitter, not just because he is responsible for the best thing that happened to my career in 2014, but also because he has coined the phrase “digital Manichaeism.” He was referring, in part, to this amazing story about Justine Sacco in the New York Times. Flying to South Africa to visit family for the holidays, she tweeted the above ill-considered joke to her 170 followers before she got on the plane. By the time she landed, she had been fired from her job and was the number-one trending topic on Twitter. Sacco became the focus of social media’s robust shaming culture, and it blew up her life.

Before we run afoul of that culture ourselves, I should point out that I don’t think Sacco’s joke is funny. I also don’t think it’s racist, exactly. A charitable reading that allows for irony sees this joke as satire of white privilege: Sacco facetiously asserts that AIDS is an African problem when it is obviously a concern for everybody. Only an idiot would think white people can’t get AIDS, but that is the unspoken assumption on which privileged Americans sometimes operate.

That’s too much nuance for Twitter. There are a lot of reasons Sacco shouldn’t have made this joke, including but not limited to the rule that white people indicting white privilege does not trenchant commentary make. But the main reason, in retrospect, is Staley’s Principle of digital Manichaeism. Particularly when it relates to social justice, any single unit of speech on the internet is either all good or all bad.

Also it is almost never good. The internet thrives on outrage and righteous indignation, as Sam Biddle suggests in his retrospective piece Justine Sacco Is Good at Her Job, and How I Came To Peace With Her.1 Biddle is the Gawker writer who saw Sacco’s tweet and retweeted in to his 15,000 followers. He also wrote a short piece about it on Valleywag—the Gawker subproperty about the tech industry—that was itself basically a retweet.

That’s how Sacco’s bad joke went from an audience of 170 people to an audience of thousands—possibly millions. Here’s Biddle’s narrative:

As soon as I saw the tweet, I posted it. I barely needed to write anything to go with it…Twitter disasters are the quickest source of outrage, and outrage is traffic…The tweet was a bad tweet, and seeing it would make people feel good and angry—a simple social and emotional transaction that had happened before and would happen again and again.

“Feel good and angry” should probably be the official motto of Twitter. Biddle hits on a foundational paradox of internet shaming culture: when other people do awful things, we feel better about ourselves. That’s the appeal of Manichaeism. If something you hate is completely bad, it follows that you are good.

Note that it does not work the other way around. If something you like is great, it doesn’t necessarily make you feel good. One suspects that’s why internet culture seems distinctly censorious. I now feel kind of embarrassed by my enthusiasm for Yes, You’re Racist, in part because it fell to retweeting the n-word screeds of people with six followers. But mostly I am bummed that there is no corresponding feed for praising good speech—a Yes! You’re Thoughtful or something.

That’s in some ways a false dichotomy; pretty much the whole non-shaming internet is a machine for promoting expression people think is good. But for the non-famous, at least, public censure seems far more common than public praise. As Biddle’s nose for news reminds us, “look at this jerk who is worse than you” sells better than “look at this great idea.”

You can see this bias at work in the response to Sacco’s tweet. In the Everett interpretation of the universe, there is an internet somewhere that retweeted her joke as a praiseworthy acknowledgment of first-world narcissism. That is not our internet. Our internet looks for reasons why any given remark is bad, and when those reasons are easily found—as they certainly were in Sacco’s tweet— it enumerates them gleefully.

That’s not a crisis, exactly, but it kind of sucks. It discourages risk-taking in idea and expression, which is probably not what we want from our ultra-democratic global communications medium. After an irreverent tweet about bullying, Biddle suffered his own internet shaming. The advice Sacco gave him captures what’s wrong with our presently censorious culture:

Without any discussion, she knew the only divine truth of the internet: Do nothing. Never tweet. Never apologize. Never say anything at all. Be an inert bundle of molecules and let the world tear itself apart around you.

The problem with populist morality, with righteous indignation and pious orthodoxy, is that it makes doing nothing the only safe position. That’s not what the internet was designed to do.

I would like to kindly refer readers to Colin Quinn on fake shock, referenced here in the Combat! blog outrage archive comments.

http://combatblog.net/?p=4718

I agree that the internet is rife with righteous indignation, and that, generally speaking, this isn’t a good thing. But I just ran across an argument on reddit’s r/changemyview that has, appropriately enough, changed my view on the matter, and I’m curious as to what you think. The argument is that the righteous indignation directed at Martin Shkreli helped bring him down. It drew attention to him, and maybe also to the larger systemic problem of which he is a prime example. This attention and the possibility of reform is a good thing, and would not have occurred (so the argument goes) without internet rage. Shkreli is, like many targets of internet rage, an easy target (about as easy as Sacco). But maybe, at least in some cases, righteous indignation yields positive results (David Sterling also comes to mind). So, do you agree that this is the case? And if so, how do we tell the difference between justifiable righteous anger (Shkreli) and non-justifiable righteous anger (Sacco)? Also, does any of this even matter? Are we just engaging in a pointless parlor game by spending time debating this? Won’t the internet just march along and get pissed off at everybody in a non-discriminant way?