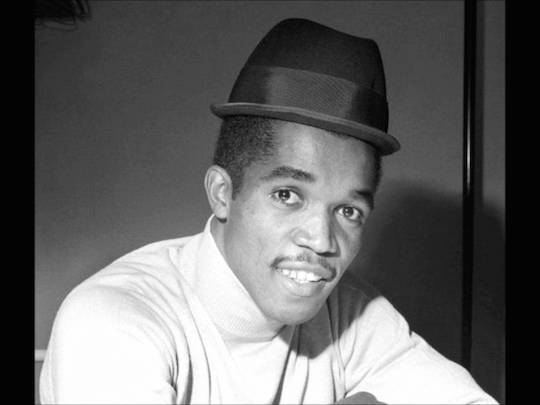

By the time you read this, I’ll be famous. I assume that everyone else on the internet also spent the last few weeks listening to Prince Buster, and this blog post about his influence on The Specials will go viral instantly. Probably, the Combat! blog server has already crashed, and this essay is now hosted by NASA. In case you live in Iraq or something and don’t know the central elements of western culture: Prince Buster was a musician during the first wave of Jamaican ska in the 1960s. The Specials were a band during the 2-Tone ska revival in late-seventies London. They relate to each other much as the individual relates to the culture he or she inherits, echoing Ortega y Gasset’s construction of modernity. Video after the jump.

Many people who hear Prince Buster for the first time wonder what the fudge is going on. In this song, a stern Ethiopian judge sentences rude boys to hundreds of years’ imprisonment for various crimes, including but not limited to “aggravation.” Clearly, this song is the product of a particular culture and moment, but what?

Ska music developed around the same time that Jamaica became independent from the United Kingdom, in 1962. Although Jamaica experienced robust growth and rising incomes from 1945-1959, most of the profits went to the upper class. Growth tanked in 1962, and young men who came to the city looking for jobs were forced to live in growing shantytowns.

As the music industry became more lucrative, these young men found work as “rude boys,” paid by dance hall owners and artists to disrupt the performances of rivals. “Rude boy” became a catchall term for any young man engaged in petty crime in Jamaica’s cities. Ska performers took to addressing these rude boys directly, urging them not to crash up the dance hall and, generally, abandon their wicked ways.

Ska’s attitude toward rude boys remains complex; songs like “Judge Dread” seem to simultaneously condemn rude boys’ behavior and celebrate their culture. That’s probably because the audiences at ska showscame from the same social stratum as the rude boys trying to disrupt them. Often, they were the same people: disenfranchised young music lovers living in the city without much money.

In late-1970s London, similar conditions obtained. The Jamaican diaspora had brought first-wave ska to England in the 1960s, where it influenced mod and skinhead cultures. By 1978, a generation of ethnically diverse lower-class men who grew up listening to Prince Buster and his contemporaries found themselves jobless in a struggling city, not unlike the rude boys of yore. Enter The Specials:

Obviously, “Stupid Marriage” owes much to “Judge Dread.” Both songs are structured around a judge sentencing rude boys, but The Specials use that premise as a framing device for another narrative: jealous of her new marriage, the rude boy has crashed up his ex-girlfriend’s apartment rather than the dance hall.1 The song still ends with his being ordered away, but “Stupid Marriage” builds to an ebullient chorus that suggests the rude boys have taken over the courtroom. In Prince Buster’s original, Judge Dread retains control.

Still, these songs are striking for their similarity more than for their differences. References to Prince Buster’s greatest hits are all over The Specials’ debut album. Frontman Jerry Dammers first heard Prince Buster when he was ten years old, along with Desmond Dekker and other artists popular among the Jamaicans who immigrated to the suburbs of London during his youth.

The sixty-dollar question: Did Dammers understand the socioeconomic forces in the years after Jamaican independence that led Prince Buster to sentence rude boys as Judge Dread? Or did he simply associate ska—the music he would amalgamate with new wave to endear himself to generations of uncool college students—with judges lecturing young men from the bench?

Here we encounter Jose Ortega y Gasset’s construction of modernity: using vertiginously complex technology without knowing how to make it yourself. Culture works the same way, in that it is the end of a long and tortuous story which we take for a beginning—a premise. It is by definition immersive, so totalizing that we mistake the condition of living in a particular culture for the condition of being alive. We stand on the shoulders of giants, but we think we are on the ground.

this is a nice piece of fiction.

everybody knows that Madness invented ska

Greg, do you even know how to use wikipedia? I always thought your crap was pilfered from there.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ska

Fuck this.