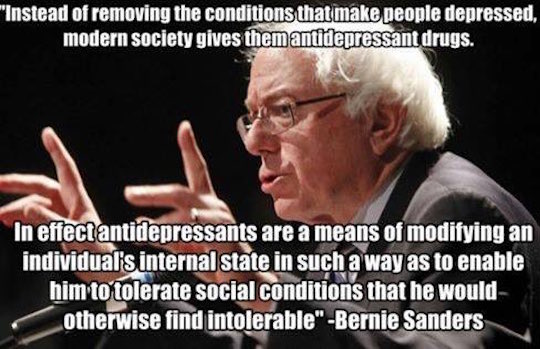

The quote on the picture above is not from Bernie Sanders. It’s from a manifesto by Ted Kaczynski, better known as the Unabomber. I ran across it on Twitter, where Anne Thériault observes with inscrutable emoji that it has been shared 11,000 times on Facebook. But just because the Unabomber said it, is it wrong? The Unabomber is definitely wrong in his position on mailing bombs to people. But his position on antidepressants, at least in this quote, echoes an idea from Sartre, who argued that depression is the only sane response to modern life. It’s worth thinking about the fact that millions of Americans must consume drugs to tolerate daily life. On the other hand, context matters. If the next sentence after this one in the Unabomber manifesto is “that’s why depressed people should be allowed to die,” we should probably withdraw our tentative concession that the murdering Luddite has a point. I was going to look it up, but then I realized that if I type “Unabomber manifesto full text” into Google, I’ll probably end up on a list.

That’s a problem. But is it a big deal? There are two tricky concepts at work in this BernieBomber meme.

One is the idea of forbidden arguers: people who are so awful that quoting them or locating merit in something they’ve said is wrong. I reject this idea. It’s tempting in a lot of situations, such as when an erratic billionaire presidential candidate starts saying stuff that resembles stuff said by Adolf Hitler.1 It’s efficient to dismiss an argument by saying, “That’s what Hitler said, too.” But Hitler was bad because his ideas were wrong. His ideas were not wrong because Hitler was bad. It’s a fine distinction, but I believe it’s critically important to productive, rational discourse.

The second tricky concept at work in my Google flinch is forbidden arguments. The United States government, without telling us about it but totally legally since we found out, tracks our internet searches. When someone Googles ISIS videos or the Unabomber manifesto, the Department of Homeland Security takes note. The reasoning is that certain people are attracted to certain subjects, and the person who uses the internet to research terrorists and murderers is more likely to commit terror or murder than your aunt, who uses it to look up cookie recipes.2 But the effect is that certain arguments become forbidden, so that the act of reading them—not agreeing with them or even just repeating them, but merely encountering them—becomes wrong.

I wanted to know how this quote from the Unabomber manifesto went, in context, but I was afraid to use the internet to find out. Is one Combat! blog post really worth being on a list that, ten years from now, might get me in trouble when I accidentally bring a quart of water through security at the airport? It is not. Explaining to the US government why I wanted to read The Collected Unabomber for totally innocuous, even vaguely patriotic reasons is just too potentially difficult, especially when they might skip my explanation and throw me directly in jail. It’s very, very unlikely that they would. But they could.

Maybe this country has always had forbidden arguments. But I can’t think of a time in US history when looking them up was as concretely dangerous as it is now. Perhaps that makes us safer from terrorists. But it also makes me feel a little less safe from my own government. Is that what we want for the home of the brave?

How people respond to an image macros like this is a great litmus test for their biases. When I found out it was a Kaczynski quote, I admit, I was a little happy. Part of me, despite my self-assurances, is biased against Sanders supporters, and that part very easily commits the logical fallacy you describe, seeing them as bad people because they agree with the idea of a bad person. Meanwhile, the 10k people liking the quote probably stop exhaling through their mouths just long enough to chortle after reading it, because anything vaguely critical of America’s institutions is right when it comes from B.Sanders. Likewise, this is a fallacy of thinking an idea good because it comes from a good person. If these 10k armchair philosophers came across the quote without attribution they would be much less inclined to like or share it. In conclusion, we should stop sharing image macros.