I can has cheezburger?

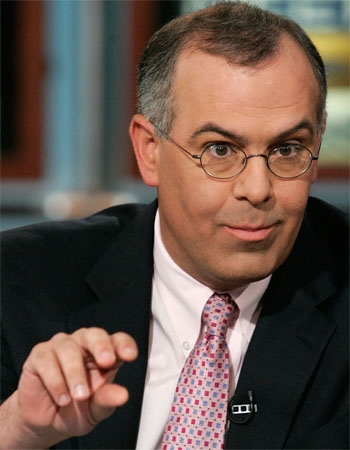

David Brooks has a pretty great column in the Times today, in which he compares the nation’s somber celebration of V-J Day in 1945 to the spectacular displays of personal aggrandizement accompanying virtually any achievement in 2009. Props to The Cure for the heads-up; I do not normally read David Brooks, as I find his foppish postures unbefitting the otherwise prestigious Brooks name. Brooks asserts that humility was the defining quality of America’s response to its victory in World War II, and any celebration of the defeat of fascism was dampened by a sense of the mind-boggling human suffering that achievement necessitated. He quotes the war correspondent Ernie Pyle: “We won this war because our men are brave and because of many things — because of Russia, England and China and the passage of time and the gift of nature’s material. We did not win it because destiny created us better than all other peoples. I hope that in victory we are more grateful than we are proud.”

That’s a far cry from Mission Accomplished and the nation that declared war in the Middle East on a mandate from god. Ask Tom Brokaw or any prep school history tutor and he’ll tell you that the United States was probably at its peak when it won World War II, and yet—at least according to Brooks’s perspective—our national touchdown celebration was more humble than most, um, local touchdown celebrations. Such assessments are risky, but I think we can safely say that we’ve become a more self-aggrandizing people than we were in 1945. The question is, what changed?

To be fair, the scope of events in 1945 encouraged feelings of individual insignificance. Brooks points out that the war produced “such rivers of blood, that the individual ego seemed petty in comparison.” The man just cannot get through one column without using the phrase “rivers of blood,” can he? He’s like Ezekiel, but I digress. When you’ve seen the sum industrial economies of Europe devote themselves to producing as many tanks, guns and uniforms as possible, then watched those tanks, guns and uniforms slam into one another in France for five years straight, it’s hard to get excited about the time you personally shot a Bulgarian dude out of a tree. The massive clashes and unrelenting horror of World War II occurred on a scale that dwarfed the individual, which probably made celebratory breast-beating feel petty. It’s like if Chad Ochocinco had to play in outer space during a meteor shower.

Still, the modern world is arguably more monstrous and epic than ever before, with no shortage of titanic forces, and that hasn’t rendered the individual ego extinct. You don’t have to be a crotchety grandfather to get the impression that people today are more self-regarding and arrogant than ever, which is pretty amazing when you consider that our sense of “how things used to be” comes from history, a place populated almost entirely by famous people. When you look at pictures from 1893, no one is wearing a shirt that says “Sexy” on it in rhinestones.* Throughout most of American history, those who nominated themselves as exceptional human beings were the object of ridicule, not admiration. One can argue that they still are, but whatever deterrent force kept people from doing it en masse seems to have been overcome.

Brooks suggests that the tipping point came in the late sixties, when a new ethos of personal freedom—what sociologists have dubbed “expressive individualism”—urged people to pursue greatness by looking within. Where previous generations had sought to aggrandize themselves by connecting to larger movements and institutions—an impulse that arguably contributed to the rise of European fascism and the outbreak of WWII in the first place—the postwar counterculture saw achievement as a process of distinguishing oneself from the crowd. Regular Combat! readers know that I am partial to any explanation that blames the sixties, but Brooks’s theory seems more appealing than true. Maybe the World War II generation were particularly inclined to see greatness as following from humble participation in great endeavors, but the Baby Boomers can’t have been the first cadre of Americans to regard self-aggrandizement as a life’s pursuit. There is, for example, Pennsylvania.

A more likely culprit is the self-esteem movement. It seems entirely possible that ours is the first generation of Americans to regard high self-esteem not as an occupational hazard of success, but success’s cause. I am a product of those years of public education during which low self-esteem was blamed for everything from poor study skills to teen pregnancy to bullying, and came of age amid a blizzard of posters, pamphlets and presentations that urged me to feel good about myself. It turns out that bullies tend to have inordinately high self-esteem, and creating a national philosophy that considers everyone special regardless of whether they have achieved anything beyond t-shirt ownership might actually have some cultural ramifications.

David Brooks cites Kanye West’s recent explosion of self-importance at the Video Music Awards as evidence that ours is a culture of expressive individualism run amok, and his commenters point out that Shoutin’ Joe Wilson is of the same ilk. Those are certainly two sad examples of men who overestimate their own importance, but it’s also worth noting that they are a multi-platinum recording artists and a United States Congressman, respectively. Kanye may be a bag of water and vinegar designed for hygiene, but at least he record “Golddigger.” For my money, the most hideous examples of self-esteem culture this summer appeared not on stages or the Senate floor but at town hall meetings. The legions of utterly misinformed Americans who get their news from chain emails and talk radio but still feel more qualified than their senators to run the U.S. government—here is the real and damaging legacy of a generation of expressive individualism. David Brooks is right: this country has an ego problem. He is looking, however, at the wrong end of the achievement scale.

* Probably I’ve trained you not to click on links by now, but did you read the product description for that shirt? And I quote: “This teen tee shirt makes a great gift and says you are one thing, sexy.” Je-sus Christ. If there’s one thing I want my child to be…

Americans are more individualistic than 60 years ago? Really? This thesis is backed up by a quote from a single war correspondent and the (probably true) supposition that folks back then didn’t sport a glittering “sexy” across their chests. Oh wait, that last example was your evidence for American’s total lack of obnoxious self-love in the 1890s.

You can put together a sentence with far more flair than anyone at the Times, but your conclusions are just as impossible to back up as the bullshit trend pieces you decry. It’s sleepy time for Mose in Paris, post-a couple glasses of pinot noir, so excuse me if I get cranky.

Americans have always been extremely self-obsessed, that’s how we invented hip hop, capitalism, and the telephone. (Yes, we invented none of those things, but more importantly we claim to have done so.) When I read the Catcher in the Rye or Hemmingway I’m reassured that our psyche is about as charmingly screwed in on itself as it always has been.

Navy Day, 1945. Los Angeles Coliseum: A massive crowd gathered to watch a re-enactment of the Atomic assault on Japan, complete with imitation mushroom cloud. I wasn’t there, but I don’t think it was a somber occasion. And today, the phrase Ground Zero has nothing to do with its atomic antecedent, but everything to do with what was done to us. Anyway, food for thought and all that.

Hi Dan! I like your blog. Keep it up.

Yo Dan, I’m really happy for you, I’ll let you finish…

Egotism seems more omnipresent today than it was [insert number] years ago? I’d say that egotism is merely more ~apparent~ given the accessibility and prevalence of means of communication. Your “more qualified than their U.S. senators” link is an example. While 54 years ago this would have been an opinion shared at the townie bar or barber shop amongst a small group of generally disinterested acquaintances, today it can be plastered up on a wall of bytes and disseminated anywhere, and anyone who cares to read it can opine in turn. I’d go so far as to argue that the impersonal nature of digital media leads to a general lack of the self-censorship that one would exercise when discussing strong opinions (informed or otherwise) in person, and THAT, in fact, is what is changing the tenor of political communication. Politics and religion are taboo to broach at the dinner table, but when one doesn’t know or care about the people across a virtual table devoid of social context, one is more apt to just blurt out whatever notions one may have.

I remember a study done in the 50’s (?) where a psychologist handed a test subject a button that when pressed would trigger an actor on the other side of a screen to scream bloody murder. The test subject was told they were administering electric shocks in ever-increasing voltages. I wonder if that same study, performed today, would elicit the same response from the test subject?

Brooks makes a similar point about how individualism took over in a column he wrote in January (http://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/27/opinion/27brooks.html?_r=1&scp=1&sq=hugh%20heclo&st=cse). While I think the new article more directly points out how celebrities are dickheads, he emphasizes the importance of institutions and that the rise of the individual has made people think that working in a group or dealing with the old guard is never a way to shine. The book he references, On Thinking Institutionally, also discusses that this is why congress has been at its most ineffectual in the last decade or 2 and how New York City prep schoolers think being educated in groups of 15 people in a school established 100 years ago is for pussies so they torture truly excellent but aimless 20- (or 30-, you’re old, dude) somethings to make sure they are able to get into a 300 year old college where they will be educated in groups of 100 or so. But I digress. What I’m getting at is that Brooks clearly believes (as do I) that conformity differs from agreement with the majority. Many institutions are institutions because of merit and adapting to work within this merit can benefit us all, even if that means that for part of your day, and part of your goal, you are using unoriginal thoughts.