On Friday night, Gloria Steinem criticized young women who support Bernie Sanders in, uh, problematic terms. “When you’re young, you’re thinking, ‘where are the boys?'” she told Bill Maher. “The boys are with Bernie.” That’s a bad argument, mostly because it implies that young women care less about politics than catching a man, but also because there’s a much more satisfying generalization right next door. When you’re young, you’re thinking, “where are the young people?” Eighty-five percent of voters under age 30 broke for Sanders in the Iowa caucuses, and he led Hillary by 21 points among voters 30-44. There may be some force at work here other than the overwhelming desire for boys. But if Steinem is a feminist, how can she say something sexist?

That question ought to be rhetorical. The sexism of a statement lies in what is said, not who said it. But the contours of sexism can be hard to make out. Whether a statement is sexist is usually a matter of opinion, and if the internet has taught us anything, it’s that matters of opinion are impossible to resolve. If you’re trying to decide whether an argument, image or criticism is sexist, it’s easier to just look at what side the woman is on.

Rebecca Traister offered an example of this principle in her November piece for New York Magazine, The Bernie Bros vs. the Hillarybots.1 Discussing a portrait of Clinton in terms of the woman and “Hillary superfan” who painted it, she calls the image “a hilariously kitschy take on an ambitious, tenacious politician long bedeviled by an American reluctance to admire tenacity and ambition in women.”

Not sexist, in other words. But in the context of Doug Henwood’s anti-Hillary book My Turn, which uses the same image on its cover, the portrait becomes sexist. Traister writes:

But since the book is far from an ode to Clinton’s moxie, the image takes on a different cast, conveying the grotesque degree to which a competent professional woman, history-making presidential candidate, policy nerd, and grandmother can be so intimidating that her menace is best portrayed as violent threat.

What we have here is a claim that Sarah Sole’s painting is not sexist when it supports Hillary, but it is sexist when it criticizes her. The salient difference in its attitude toward women is the painter/author’s attitude toward Clinton.

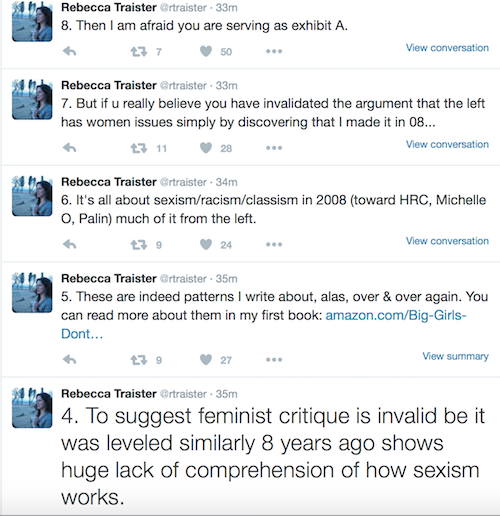

I mention Traister because this morning, Matt Taibbi and Glenn Greenwald tweeted links to an article she wrote in 2008 headlined Hey, Obama boys: Back off already!. It is remarkably similar to the Bernie Bro narrative she espouses in 2016. But this criticism is itself sexist, as Traister explained in a series of tweets this morning. Don’t forget to read from the bottom:

First of all, no one is suggesting that the feminist critique is invalid. Greenwald and now, I guess, Taibbi are suspicious of the Bernie bro narrative because Traister advanced the same argument about people who voted against Clinton in 2008. The idea of the Bernie bro relates to feminism, for sure, but it is not itself a feminist critique. It is a claim about the demographics of a political campaign. But what’s most unsettling about Traister’s reasoning is its conclusion: to cast doubt on a claim of sexism is itself sexist.

If you weren’t sexist, she implies, you would agree with me when I say these other people are. But what if the flaw lay in Traister’s reasoning and not the principles of feminism itself? As with Sole’s portrait, the factor that determines sexism here seems not to be what is said, but whom it supports or criticizes. It’s sexist to say a woman’s claim of sexism is mistaken. It’s “hilariously kitschy” to paint a scary portrait of Hillary, but that portrait becomes sexist if you use it against her.

That’s a dangerous way to think. It reduces centuries of feminism to the benighted place we started: do you like the man or the woman? There has to be some reason that isn’t sexist to prefer a male candidate to Hillary Clinton, or the whole critique collapses into a different hierarchy of genders.

Understanding and applying the feminist critique is hard. It’s much easier to decide what’s sexist by looking at who’s speaking. But that approach turns feminism into the caricature presented by Rush Limbaugh and Phyllis Schlafly. There is more to feminism than backing the woman. Hillary Clinton is an opportunity to put a woman in the White House, and that would be a milestone. But is it worth it to get there by convincing people feminism means agreeing with the woman?

You raised my curiosity so I actually watched the Steinhem clip. She is talking about how women get more radicalized as they get older, as they lose power (contrasting with men who gain power and become more conservative). Also she starts the conversation by mentioning how she’s impressed with how feminist young women are. It seems disingenuous to rip one comment from that conversation that comes across as not feminist. And in this case, seems relevant to the question ‘if Steinhem is a feminist, can she say something sexist?’