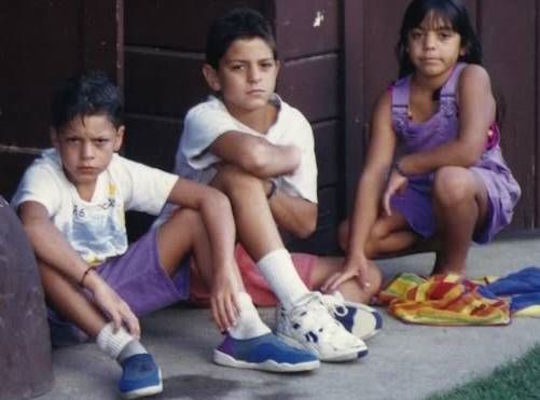

Nick Diaz submits Takanori Gomi via gogoplata in 2007. His win would be overturned following a failed drug test.

Yesterday, the Nevada State Athletic Commission suspended Nick Diaz for five years and fined him $150,000 for failing a drug test after his January bout against Anderson Silva. Diaz tested positive for marijuana metabolites. His opponent tested positive for anabolic steroids and was suspended one year. The asymmetry between these punishments is not as clear as it may seem: Diaz has tested positive for marijuana twice before, in 2007 and 2012. That might be because he has a medical card in California, where he lives, but whatever the reason, Diaz smokes a lot of weed. As of yesterday afternoon, that seems to be the central problem in his life.

Diaz is 32, so this five-year suspension will likely end his career as a mixed martial artist. That seems somewhat harsh for a drug generally agreed not to be performance-enhancing, especially when you consider that this is the longest suspension ever handed down by the NSAC. Amendments to the commission’s code that go into effect later this year prescribe a three-year suspension for a third marijuana offense. But although Diaz is a fan favorite, he is not well-liked among promoters and regulators.

He is notorious for missing media events. In 2011, days before he was set to challenge Georges St.-Pierre for the welterweight title, he failed to appear at a press conference and was removed from the fight by the UFC. Ben al-Fowlkes once traveled to Stockton to interview Diaz and never saw him. He is notoriously sullen and hostile with the press, and routinely taunts his opponents in the cage, even into the second and third rounds.

Diaz brought his combative belligerent pugnacious fighting attitude with him to the NSAC hearing yesterday. He also brought an attorney, Lucas Middlebrook, who aggressively challenged the validity of Diaz’s positive test. Diaz provided three samples on the day of his fight with Silva. Two were analyzed by World Anti-Doping Agency-approved laboratories and came back negative. One was analyzed by the non-WADA-approved Quest Diagnostics and came back positive. This positive result was the basis for the commission’s decision to suspend. Middlebrook challenged the validity of this process in strong terms:

There is simply no medically plausible explanation for the Quest result of 733 ng/ml—none whatsoever. Yet in arbitrary and capricious fashion, this commission has filed a disciplinary complaint against Mr. Diaz in a situation where two tests results from a WADA-approved lab produced negative results: negative results that bookend the erroneous result within a matter of hours, yet the complaint makes absolutely no mention of those two negative tests. None whatsoever. At best, this is an ostrich-like head-in-the-sand mistake. At worst, this is a gross and blatant misrepresentation of the facts.

No less an authority than Ben al-Fowlkes has suggested that the harshness of Diaz’s punishment resulted from the vigor of his defense. “Because while these hearings might at times mimic the look and feel of a court proceeding,” he writes, “that’s just a facade. It’s a game, really. The worst thing the accused can do is actually try to win that game, since it only makes the punishment worse in the end.”

Of course, the other striking aspect of Diaz’s defense was that everybody knows he smokes weed. He has a prescription, for Pete’s sake. Pretty much every video produced by his camp that does not feature actual fighting features a bong. During the hearing, he refused to say whether he smoked the day of the fight. It would be crazy if he did, considering he was slated to fight the most dangerous striker in the history of the sport that evening. But anyone who has followed his career considers it plausible.

Diaz is a professional athlete who competes in triathlons as a hobby, but he keeps smoking weed. He keeps smoking weed even though it has undone some of the biggest wins of his career, including his beautiful upset of Takanori Gomi in 2007. He could have saved himself five years and $150,000 by not smoking weed for maybe six weeks before he fought Silva, but he kept doing it.1

That’s probably because he is a deeply damaged human being. I urge you to read the entire interview Diaz gave Ariel Helwani after the hearing, but here’s a taste:

I’m the only one who’s invested in a fight life. That’s why none of these other guys can ever say shit. They’re too worried about what their families and their wives and the people around them will think, so they’re too scared to speak up. That’s why I invested everything in my fight life. That’s why I come off the way I do and always have.

Every other fighter has a life on the side. I’ve never had another job. I didn’t graduate eighth grade. I could have, but I got into too many fights in middle school.

My mom and dad taught me nothing but ABCs. I was moved from school to school, put on drugs and made fun of by classmates because after being disruptive in class the teachers would always tell the other kids I was on meds and sometimes don’t take them.

He goes on to describe the suicide of his girlfriend on the night before his first professional fight. It’s a harrowing, rambling and often self-pitying monologue. What comes through most, though—besides his sense that the world is against him, and his questionable belief that he’s the best fighter in it—is how little Diaz has besides fighting. He loves his brother. He loves jiu jitsu. Otherwise, pretty much everything disgusts him. He is a middle-school dropout who is incredibly good at fighting and has almost no other skills.

Because of the suspension, he can’t corner his brother in his upcoming fight against Michael Johnson. Nick has always been a guiding figure in Nate’s life, and the older Diaz feels responsible for his brother’s decision to take up fighting as a career:

But in the end, I’m just upset I can’t be there for my brother right now since he’s gonna be fighting soon. It’s my bad he even got into this sport and he gets his face kicked in and they don’t even pay him. I got us in this, and if I don’t make any money, I don’t have any way to get us out.

Maybe they were right to do it, but the NSAC hurt Nick Diaz yesterday. One of the most frustrating and fascinating athletes in the sport has been effectively kicked out of it, and now he genuinely has nothing. One suspects he will keep smoking weed. Unless his appeal is successful, though, he will stop fighting. An unhappy kid from Stockton has lost the greatest source of meaning in his life, and fight fans have lost a favorite. I guess that’s justice, but it doesn’t feel good.