The classic example of political satire is Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal,” in which the Irish author, writing ironically,1 suggests that the poor families of Ireland might ease their burden and contribute to society by selling their children as food for English aristocrats. This was in 1729, after which England immediately began treating the Irish well. Either that, or right-thinking people agreed Swift was a genius and went on treating poor people like dirt for the next three centuries. I mention this gap between reception and effect on the occasion of this hilarious McSweeney’s piece by Jeff Loveness, titled This is the Political Satire That Finally Stops Trump. A taste:

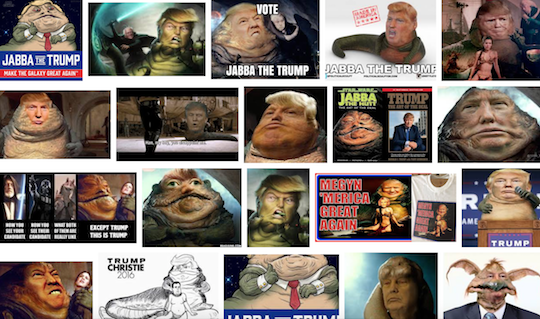

I tweet my “Jabba the Trump” meme for the world to see. The knife of satire twists deep. In a moment, I am flooded by dozens of retweets, ranging from friends who share my political opinions to strangers on the internet who also share my political opinions—the chorus of America itself. My tweet lights the spark, and the fires of rebellion burn bright.

You think it’s going to be one-note, and it kind of is, but the crescendo is so strong that we don’t miss the melody. It also makes an uncomfortable point: Now that Trump has ascended to power through sheer absence of shame, what can mockery and ridicule accomplish?

Much has been said about how Trump is somehow beyond satire or has, by expedients such as Kellyanne Conway’s “alternative facts,” rendered satire obsolete. I reject this claim. In his combination of crowing arrogance and refusal to prepare, Trump is satire ready-made. Not only is he a confident idiot—perhaps the funniest archetype in comedy—but he also comes with recognizable speech patterns and a ridiculous appearance. These qualities are, of course, the crux of the argument: Trump obviates satire because he is a satirical character come to life. But if I gave you an afternoon to write something funny about the president, would you rather work with him or Hillary Clinton? Trump is not beyond satire. If anything, he makes satire too easy.

Here lies the problem. By being so eminently satirize-able, Trump demonstrates the limitations of the form. If you set out to satirize Hillary, you might get a tepid result and conclude that you didn’t think hard enough. When you set out to satirize Trump, you’re much more likely to knock it out of the park. It’s like batting off a tee. But because he is so readily mocked, the many satires of Trump that did not derail his candidacy or halt his relentless dicketry cannot be said to have failed artistically. They failed politically.

That’s weird, because recent events have shown Trump to have one main weakness: vanity. The Women’s March on Washington, for example, threw him into a tailspin. It encouraged him to embarrass himself by insisting the inauguration crowd was huge, lured him into the unforced errors that were Sean Spicer’s first press conference and Kellyanne Conway’s instant-classic “alternative facts,” and turned his first weekend in office into a 48-hour public relations disaster. If you want Trump to unravel, suggest that he is unpopular.

So why doesn’t the public mockery of satire drag him down? The problem, I suspect, lies with satire’s knowing quality. It is especially prominent in Juvenalian satire like Swift or The Onion, which relies on irony or sarcasm to send a subtextual message that contradicts what is explicitly says. But it’s also a generic hallmark of Horatian satire, which is less straight-faced but still relies on its audience to recognize humor subtly presented. This knowing air is poison for Democrats right now.

Trump succeeded with an anti-elitist narrative—despite his status as a billionaire who appointed a bunch of other billionaires to his cabinet—because the right has successfully painted liberals and leftists as smug. A knowing laugh at other people’s folly enrages the Trump voter. Right-wing memes don’t satirize Democrats; they just explicitly call liberals pussies. The knowing attitude by which the satirist invites the audience into conspiracy against popular hypocrisy is precisely the attitude Trump ran against. His pitch is that knowing people will never laugh at you again, because if you accidentally contradict yourself or say one thing and do another, majority strength will back you up. The single biggest demographic difference between Trump voters and Clinton voters was education. He is taking this country back from the kind of people who get jokes.

This is the paradox of satire and its fundamental weakness: its purpose is to change minds, but its tactic is to speak to the wise few. I don’t want to overstate this point; you don’t have to be a exceptional wit to get South Park. But satire invites you to think of yourself that way, to see through conventional wisdom and so-called “common sense” to something smarter, if less popular. Trump’s promise to America is that common sense is all you need. He invites us to be dumb with him, and with the ostensible majority of people who can’t see through his act or don’t want to. The corrective is not to invite these people to join our smug minority.