During a flashback in the episode of The Simpsons where Homer and Grandpa enjoy brief success selling a homemade aphrodisiac, child Homer says he hopes to someday be President. “Son,” his father says, “this is the greatest country in the world. They’ve got a whole system to prevent people like you from becoming President.” We are now in the first presidential election year since Citizens United v. FEC, and the richest man ever to run for that office has been goaded into releasing his tax returns. In 2010, Mitt Romney received an adjusted gross income of $26 million—approximately 500 times what I made. He paid a federal income tax rate of 13.9%, around four points lower than what I paid. In Romney’s defense, almost all of his income came from investments and his inheritance, whereas my income came from wage work, which is taxed at a higher rate. In my defense, fuck Mitt Romney and the federal corporatocracy he hopes to captain.

In most cases, identifying a problem with a noun evinces shoddy thinking. The American political system of 2012 is beset by one particular hobgoblin, however, and that is money. How else to explain why our representative government has applied one of the lowest tax rates to a kind of income that overwhelmingly goes to the richest people? Fifty percent of capital gains in the United States go to the wealthiest .1% of Americans. Federal income tax on capital gains dropped from 35% in 1978 to 25% under Reagan and Clinton, and then to 15% under Bush II. Why a generation of elected officials would do so much work on behalf of such a small portion of the electorate is unclear. Whoever those .1% of Americans are, they must be extraordinarily good at organizing voters.

Either that or they have a lot of money. While one unemployed man who made $21 million last year campaigns on a platform of more jobs, another gazillionaire has donated another $5 million to defeat him. Miriam Adelson, the wife of Sheldon Adelson, has brought her household’s total contribution to the Gingrich Super PAC to a total of $10 million. That money will likely be used to purchase radio and television advertising in Florida, where Republican voters will make an informed decision about which candidate best represents their interests based on healthy debate among themselves. Or they will watch hours of television, as did the voters in South Carolina, and the candidate who suddenly has several extra million dollars to spend will come from behind and win.

Probably, Newt Gingrich was going to win South Carolina anyway. Probably, one old man who made a fortune building casinos did not personally alter the course of the 2012 election, just as his wife will not personally alter same by spending the same amount of money. But regardless of whether $5 million will buy a substantial percentage of the vote, we must acknowledge that for 99% of Americans, the question is academic. Although I gave a larger share of my income to the federal government last year, I cannot spend millions of dollars to advance my personal choice for President. I just get to vote.

In this context, the American democratic republic is not a two-tiered system, in which the people select who will operate their government. In 2012, when anonymous donors can spend unlimited money to support or attack candidates, the people function as a sort of audience. We can applaud or boo particular candidates come November, but we have little power to determine who appears onstage and how often. The millionaires do that. And the millionaires have put forth two millionaires for our consideration.

Sure, there’s still the crazy doctor and the church guy, either of whom has maybe put together enough money to make it to November. But practically the 2012 Republican nomination is a contest between the guy who wants to lower his own income tax by 40% and the guy who wants to eliminate it entirely. A tax cut for the middle class? To paraphrase John Boehner, that one is dead on arrival.

Consider the following question: why, in pursuit of one of the more hotly-contested nominations in recent memory, has neither candidate proposed big, expensive cuts to taxes on earned income? The vast majority of voters work for their money, at a ratio well above five votes to one. One would think that a dollar spent spreading the message of reduced taxes for people with jobs would win more votes than a dollar spent arguing that you’re even friendlier toward investment income than the other guy. But in 2012, the votes don’t matter as much as the dollars. We’re Americans, so we each get one vote. How much money do you have?

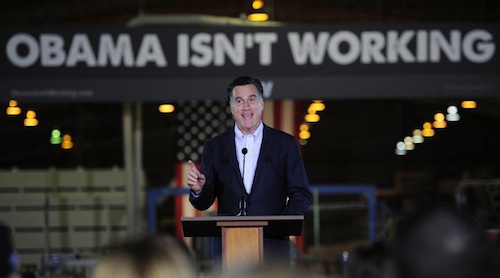

This photo is good, but I’m pulling for a surge of Gingrich because you’ve been doing wonders with Gingrich photos and captions.

On the other hand, “campaign spending isn’t nearly as influential in elections as the conventional wisdom holds.”

http://www.freakonomics.com/2012/01/17/how-much-does-campaign-spending-influence-the-election-a-freakonomics-quorum/

Even if the assumptions made in that freakonomics article are correct, it doesn’t matter. The candidates sure seem to think the money is important, or why would they devote so much effort to fundraising? When they reach office they create policy that ensures their corporate funding doesn’t dry up, again because they believe it is necessary.

regarding the difference money makes in campaigns, see Thomas Ferguson’s “The Investment Theory of Politics.” As theories go in political science, his has amazing predictive power: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Investment_theory_of_party_competition