You can advance two broad arguments in favor of democracy. The first is that it is morally right, either because people naturally deserve a say in what their governments do or because God likes it. The founders made such arguments in the Declaration of Independence and elsewhere. The other argument is that democracy is the best way to solve problems. Sooner or later, this argument goes, aristocracy or a dictatorship will run into competence problems. With no mechanism to hold them accountable, aristocrats and despots will do a bad job.

I find both these arguments convincing, but the second one is probably more useful. The first one requires us to agree on values—either a supreme being that has ordained democracy as the best system of government, or a compassionate humanism that makes the rights of individuals inalienable. Those values can break down. The idea that we all face collective problems, and that the collective wisdom of the American people can solve them, seems more robust.

But in order for this construction of democracy to work, we have to agree on facts. We can argue about the best way to structure the tax code, but we have to agree that the government needs money and can collect it from people. Some people might argue that the government has no right to tax people at all, but they still agree that taxation is real. Its possibility is a kind of fact. Such agreements often seem so obvious that they are tacit, but it’s also possible for them to break down. Take climate change, for example.

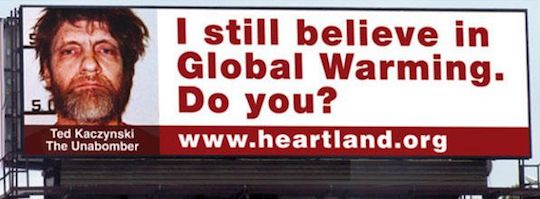

The New York Times published a fascinating story Sunday about the difficulties of teaching biology at a high school in Ohio, where many students regard not believing in climate change as an element of their identiy. Although they don’t know much about many subjects, they know that people like them say global warming isn’t real. As a result, rejecting classroom teaching about how carbon works or what scientists agree on has become an expression of their identities. This poses a problem, not just in high school but in American society.

In order to participate in the democratic approach to solving problems, we have to agree on certain facts, e.g. our behavior is changing the climate. But agreeing with that premise makes some people feel like their democratic agency is being denied. Denying it has become their way of asserting themselves as free citizens.

That’s Republicans’ fault. The GOP has made itself the brand of cultural refusers. Even though it advocates for traditional social values and the economic agenda of the rich, it has come to represent defiance of the mainstream. It’s a reversal of the countercultural politics of the late sixties, and it probably came about because of them. Liberals won the culture war so completely that they made conservatism cool, at least among the people who buy into it. For that bloc, right-wing politics is defiance, and any act of defiance can be right-wing politics.

Call it the politicization of identity. Gun ownership is a political statement. Driving a big truck is a political statement. Working outside or having a goatee is a political statement. In the same way that capitalism steadily commodified the 19th century, turning previously homemade products like clothes and food into consumer goods, democracy has politicized the 21st century. This process is bad, because it’s a force for reification. It makes our problems more difficult to solve, because it makes people resistant to changing their minds.

It’s one thing to change your position on an issue. It’s another to change who you are. While many of us like to imagine ourselves as independents who are at least hypothetically open to changing our minds, nobody wants their identity to be flexible. We can see this phenomenon at work in the classroom from the Times story, where rejecting scientific consensus is not about policy or reasoning but rather a way for those kids to keep it real.

There are two promises of American democracy: that we’ll decide what to do together, and that outside those decisions each of us can do what we want. What happens when believing what we want short-circuits our ability to decide together? Does democracy retain its authority when substantial portions of us simply don’t believe in science? The system has always depended on an informed citizenry. What place can it make for people who define themselves by refusing to learn?