Around here we occasionally take swipes at the Baby Boomers, alleging that they have, for example, constructed a culture around catering to their own narcissism that they now blame for everything. But the real objection to the boomers is that there are so many of them. That’s why so much TV in the 1980s was about the 1960s—or simply about being thirty—and why in August we declared that a 66 year-old had the best body in the world. It’s also one reason why it’s so difficult for a person my age to buy a home, and probably why half the country insists we cut all functions of government except Social Security, and maybe why the financial services industry dominates the economy and Congress. The Baby Boomers bought all the houses and made all the money and voted in all the congresspeople already, and now they are enjoying a well-deserved lockdown on society after five hard decades of mere dominance. If all this sounds like unsourced complaining to you, consider the news from the Pew Center that, in 2009, the gap in wealth between young and old reached an all-time high.

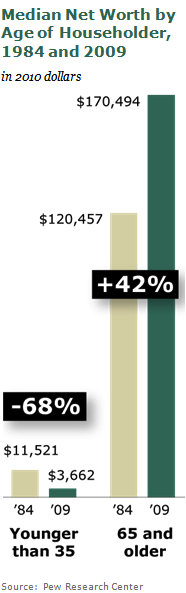

Old people almost always have more money than young people, as you might expect. But the Baby Boomers have done a terrific job of having much more money than their children—certainly better than their parents did. Back in 1984, the median net worth of a household headed by someone 65 or older was ten times that of the household of the median 35 year-old. In 2009, 65 year-olds had a median net worth forty-seven times that of 35 year-olds. Since 1984, the worth of the median 65 year-old has gone up 42%. Meanwhile, the worth of the median 35 year-old has dropped 68%. There’s a chart.

someone 65 or older was ten times that of the household of the median 35 year-old. In 2009, 65 year-olds had a median net worth forty-seven times that of 35 year-olds. Since 1984, the worth of the median 65 year-old has gone up 42%. Meanwhile, the worth of the median 35 year-old has dropped 68%. There’s a chart.

Unsurprisingly, a major factor contributing to this change has been housing. Most boomers purchased their homes before the housing bubble really swelled and then, you know, destroyed the economy. Although older homeowners lost equity in the housing crash, too, the value of their homes generally improved over the long term. Younger people, on the other hand, tended to buy houses during the bubble, only to see those houses decline precipitously in value. Net worth is assets (house) minus debts (mortgage,) which might explain why the median worth of a 35 year-old in 2009 was less than the median monthly paycheck for a 65 year-old.

There’s also college. Tuition has skyrocketed over my lifetime, in tandem with the general expectation that everyone without a closed-head injury should get a bachelor’s degree. Here Pew merits quoting at length:

For the young, these long-term changes [in factors affecting net worth] include delayed entry into the labor market and delays in marriage—two markers of adulthood traditionally linked to income growth and wealth accumulation. Today’s young adults also start out in life more burdened by college loans than their same-aged peers were in past decades, as documented in a recent Pew Research report. At the same time, growing numbers are in college, and college education has been found to confer a significant financial payoff over the course of a lifetime.

The methodology is interesting here, since when Pew notes that a college degree has been shown to lead to “a significant financial payoff over the course of a lifetime,” they mean over the course of the Baby Boomers’ lifetimes. Thirty-year income statistics are not available for people who graduated in 2001. Considering that a much larger percentage of the workforce has college degrees now—and that the debt incurred getting a degree can prevent a 2001 graduate from buying a home, which correlates strongly with net worth—it’s likely that a BA will not do the same thing for me that it did for my parents.

I encourage you to read the entire Pew report, since pretty much every paragraph offers a new and frightening indicator. The share of households in poverty, for example, has declined by two thirds over the last three decades among 65 year-olds—and doubled for those under 35. Like our contemporary rich, our contemporary seniors are historically wealthy at a time when everyone else has seen their lot worsen. What that means is another question.

On one hand, the Baby Boomers hardly caused the housing crisis. I mean, they created the investor markets and deregulated the banks that offered the predatory loans that caused the crash, but they didn’t mean to. And they can hardly be blamed for the increase in tuition costs and wealth- and investment-friendly tax structures of the last three decades. They ran those colleges and elected those representatives, but it’s not like they did it on purpose. The American socioeconomic system is big and complex, and millions of people participate in it. If things have gotten very good for the Baby Boomers and very bad for my generation since 1984, some share of the responsibility lies with the people whose worth and prospects fell during that time. America runs a fair system, and it is a sad commet on our generation that we failed to make the same bright lives for ourselves that our parents did over the last 30 years, possibly because we were children. I was 16 in 1994. That was back when we had a chance to turn this thing around, but I personally spent the year sitting on my ass. In history, as in parenting, we have no one but ourselves to blame.

I think when global warming forces Oceanic environmental refugees to pack up and move to Siberia the ancestor blame-game is really going to get exciting.

This is really one of your best in a while.

This site offers nice featured YouTube videos; I always get the dance competition show video clips from this website