Strangely, perhaps even depressingly, the big deal in last week’s revelation of massive domestic NSA surveillance is how not a big deal everyone thinks it is. According to a Washington Post/Pew poll, 56% of Americans consider secret court orders that allow the NSA to access millions of phone records “acceptable,” while only 42% consider it “unacceptable.” Forty-five percent say the government should be allowed even more leeway than it already has secretly gave itself, provided that power is used to fight terrorism. Even though half of Americans presumably do not regard themselves as terrorists, they believe their government should be able to arbitrarily investigate them, because terrorism. At the risk of pique, this is the same country that refused expanded background checks for gun purchases as an unconscionable infringement on the Second Amendment.

To be fair, it was Congress that refused background checks as an unconscionable i on the 2nd a, not the general public. Besides, mass shootings of schoolchildren and moviegoers aren’t terrorism. As Conor Friedersdorf points out, guns, diabetes and drunk driving kill far more Americans than terrorism annually, even in 2001. But the specter of international terrorism scares us much more, even though we are statistically more likely to be struck by lightning than to be killed in a terror attack.

If the government required us all to wear rubber-soled shoes in order to reduce our vulnerability to lightning, people would picket in the streets. Yet the government’s decision to require us/our telecom providers to turn over our phone records—made in secret and acknowledged only after it was leaked—has been greeted as a necessary measure to defend ourselves against a threat quantitatively less threatening than a rush-hour commute.

In short, the terrorists won. In 2001, Osama Bin Laden wanted to commit a symbolic act that would make Americans so afraid of foreign terror that we would fundamentally change our way of life, and it worked. It worked beyond all proportion to the damage it actually caused. Twelve years after September 11, 2001, we have created an enormous domestic security apparatus that can secretly spy on millions of us in flagrant violation of the Bill of Rights, get caught, and suffer only the mild opprobrium of less than half the country.

This fundamental change in the relationship between Americans and their government is all thanks to the War on Terror, a war that has primarily consisted in bombing remote foreigners and treating![]() every person at home as if they were a suspect,* both legally and psychologically. By all metrics but one, the War on Terror is not a war. It identifies no nation as our opponent; it has neither an objective nor a prescribed theater. The only way the War on Terror resembles an actual war is in the powers it asks us to give to our government. In this area—the power to surveil us, the power to determine its own conduct in secret, the power to disregard individual liberties—the executive branch insists that the War on Terror is no different from World War II.

every person at home as if they were a suspect,* both legally and psychologically. By all metrics but one, the War on Terror is not a war. It identifies no nation as our opponent; it has neither an objective nor a prescribed theater. The only way the War on Terror resembles an actual war is in the powers it asks us to give to our government. In this area—the power to surveil us, the power to determine its own conduct in secret, the power to disregard individual liberties—the executive branch insists that the War on Terror is no different from World War II.

We don’t have the war, in other words, but we have soft martial law. There is a big difference between where we are now and house-to-house searches on darkened streets. But the United States government of 2013 reserves the right to know whom you communicate with, what you buy and what you read on the internet, and it considered its right to know so natural that it did not feel obliged to tell us about it.

The rationale is that domestic spying saves American lives, but the war in Afghanistan has killed more Americans and allies than 9/11 did. Roughly as many Americans died of food poisoning in 2001 as were killed at the World Trade Center. The real problem is not the danger of being killed in a terrorist attack, but the fear of it. If only there were a name for widespread fear that prevents us from thinking reasonably about our values.

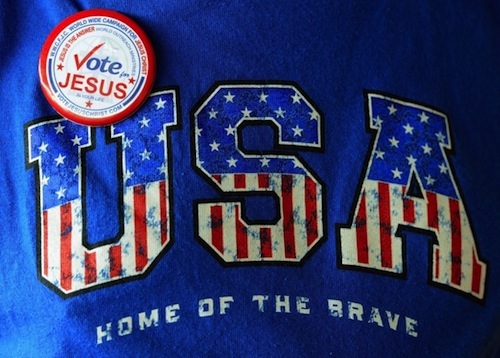

If only the words “home of the brave” were something more than a political catchphrase. Now that we have retroactively approved the secret policing of our correspondence to protect ourselves from a scary thing that happened a decade ago, what are Americans meaningfully brave about? We fear terrorism. We fear fear itself. At least we’re still the land of the free.

“But the United States government of 2013 reserves the right to know whom you communicate with, what you buy and what you read on the internet, and it considered its right to know so natural that it did not feel obliged to tell us about it.”

Secrecy is the part of this whole mess that makes the most sense. Throwing billions of dollars away trying to remedy terror is stupid, but if you are going to try and fight lean networks of terrorists, you need intelligence. To obtain that intelligence, you need the terrorists not to know how you’re monitoring them. If you tell the opposition how your methods work, they go do something else.

This has happened multiple times since 2001. Someone leaks details to the press, and the terrorists find out the cell phones they thought were impervious are not, leading to a period where counter-terrorists are deaf and blind until they can require how terrorists are communicating (Kenney, 2008, http://www.amazon.com/From-Pablo-Osama-Bureaucracies-ebook/dp/B001RTST4C). Have you seen Zero Dark Thirty? Its plot is largely about trying to capture couriers because the Al Queda is sending messages orally. They weren’t in 2004 when we were dismembering its limbs.

Does talking about counter-terrorist tactics seem like I’m missing the point? Is secrecy is something Americans should be existentially afraid of? I want to be 100% against anything related to “war on terror,” but insofar as some dimension of it is killing people actively plotting to do harm, we’ve done a good job. I was unburdened by this inconvenient truth at one point, but now I have to accept there is a point to secrecy. It’s not a symbol of machinations or rashness, even if you would like it to be one.

Why? Because there is no evidence the decision gather phone and other data, even of Americans, was done so anything but carefully. There is no evidence it was done so carefully either. Such is secrecy. Making the assumption that the rationale is one way or another is not fair.

But whatever, fairness is a judgment that has a lot to do with political outlook. The real risk is that we criticize the rationale of the administration and NSA rather than the public which charged them with the duty to prosecute the “war on terror.” The secrecy element is solid and sensible. But it’s a branch growing on a tree with rotten roots. If we fear a loss of liberty we shouldn’t wage a “war on secrecy,” we should wage a “war on the war on terror.”

I got lost in the moralizing. For posterity I want to add that there are plenty of very sensible ways to reform the details of how secrecy operates. In theory there’s a sweet spot where secrecy and oversight intersect that preserves both operational intelligence and American liberty. My boy Wyden is leading the charge on that kind of reform.

http://www.wyden.senate.gov/news/press-releases/senators-end-secret-law

I think the word you’re looking for that means ‘widespread fear’ is ‘terror’; as in the phrase ‘war on ohhhhhhh I see what you did there.