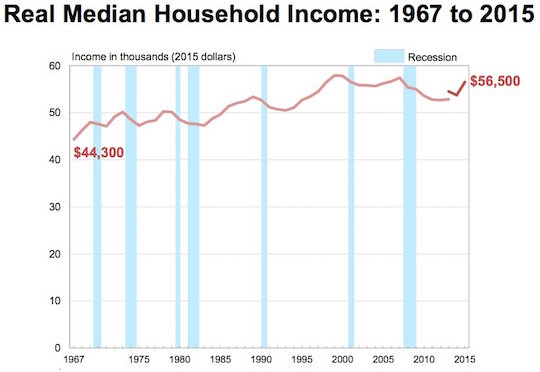

The median income of an American household increased 5.2 percent in 2015, the largest single-year increase since 1967. The poverty rate also fell, and the portion of Americans without health insurance fell to about 10 percent. That’s good news, especially during a recovery whose benefits have disproportionately gone to the very rich and large corporations. The bad news is in the graph above. You will notice that median incomes have risen after the each of the seven recessions of the last 50 years except for two: the last two. Although the historical trend has been for incomes to exceed or at least return to their pre-recession levels during each recovery, the median income is still lower than it was in 2007 or, for that matter, 1998.

The Times article on this exciting 2015 data also notes that median incomes haven’t really risen because wages went up, but rather because more people are working and/or investing. It’s probably good that more households are joining the investor class, given that the stock market has achieved record highs since the last recession. But it’s frustrating that those highs haven’t translated into increased wages. The American dream is to work hard and get ahead, not to invest wisely and reap the benefits of market trends. Although the 2015 census data is almost unequivocally positive, it is not good news to hear that people are working more and getting paid less to do it.

What’s to be done about this problem? Economics is not really a science, in that way too many variables affect economic outcomes for us to isolate one and figure out how it works. Even if it were possible, to do so would require massive government intervention that would disrupt millions of lives. But is that not what we’re doing anyway? When, for example, we bail out banks after an economic crash, we perform a focused intervention on one segment of the economy, on the hypothesis that its effects will reverberate throughout the system.

I think the bailout and stimulus were good decisions, but I don’t know enough about economics to say so with authority. It’s possible no one does. One thing we do know, though, is that the process of financialization is shifting the mechanism of American success1 from work to investment. I think that’s reflected in the massive shift of wealth away from workers and toward the investor class.

It’s an interesting example of unintended consequences. If you asked Americans how Americans should get paid—according to their work or according to what they already own—most would choose the former. That’s not where we’re headed. Maybe it’s because our political leaders are increasingly drawn from the investor class and mistakenly imagine it to include most Americans. Maybe it’s because the stock market is easy to quantify, so it has become the metric of economic success. Maybe it’s because financial services has become a much more powerful lobby than labor.

Whatever the reason, the last two decades reflect a fundamental change in how the American economy works. It’s been working worse for people who work and much better for those who don’t have to. Maybe that’s what we want, and there is no dark cloud in the middle of yesterday’s silver lining. Maybe, though, we should do something about it.