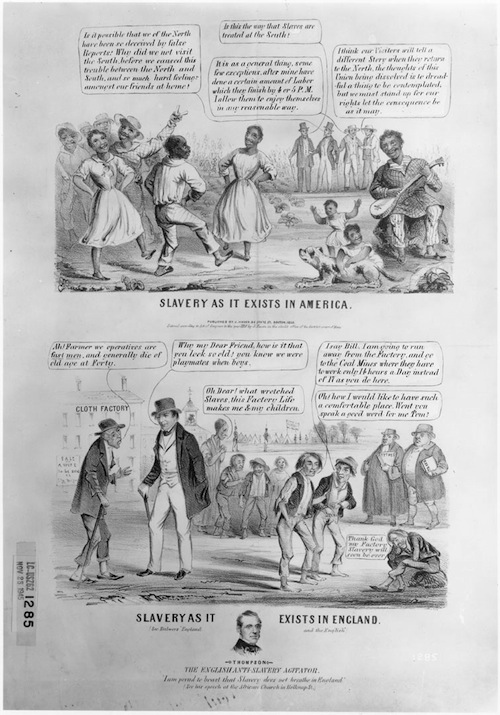

The above political cartoon hails from around 1861, and it advances an argument popular in the South during that time: that slavery was analogous to the factory system in industrialized England, only preferable because it made black people happy and white people, you know, not stunted mill workers. You must not try to read the dialogue in the image above, or your retina will focus all the light in the room into a laser that burns through your brain; read this one instead. “Is it possible that we of the North have been so deceived by false Reports?” marvels a gentleman visitor to the South, where his friend’s slaves have finished work early to have some sort of dance party. “Why did we not visit the South before we caused this trouble between the North and South, and so much hard feelings amongst our friends at home?” Here it should be noted that the dialogue in this cartoon predates the development of naturalism, which sort of explains why a British mill worker in the bottom half of the image would casually remark, “I say, Bill, I am going to run away from the Factory and go to the Coal Mines, where they have to work only 14 hours a day instead of 17 as you do here.” Bill has to listen to this shit all the time, but he knows they’re both going to work at Cloth Factory for the rest of their lives.

The argument advanced in this cartoon was part of a broader moral theory popular among Southern apologists, who held that slavery made possible a more just and egalitarian way of life, at least for white people. They didn’t have a word for that particular species of bullshit yet, since George Orwell wouldn’t be born for another 42 years, but it was still an absurdly hypocritical argument. Yet to the vast majority of northerners during the years before the Civil War, it was unfalsifiable. The average resident of 19th-century Concorde would never see New York, much less Mobile, so he could never be sure that such claims weren’t true. For the same reason the artist believes that withered English millhands start every sentence with “I say,” beginning with their acquisition of language and continuing until their deaths at age 40, most people in the North could not know for certain whether slaves were happy or not.

They had reason to believe they weren’t, obviously. But the claim “our slaves are happy” became such cant among southerners that it lost some of the blinding sheen of its mendacity, until those who still wished to argue about slavery had to treat it is a legitimate position. Slavery does sound like a pretty awesome system if you can convince yourself that the slaves are into it, so patriotic southerners had an incentive to try to believe, too. Particularly if they themselves did not own slaves—and most southern whites didn’t—the alternative self-image was of a gear in a torture machine.

So “slaves are happy” became a sort of rhetorical meme, reproducing itself in arguments over slavery as a tactic if not a sincerely compelling point. Because increasing tensions between North and South coincided with A) a massive and rapid expansion of voting rights, which had previously been the privilege of propertied men* and B) the growth of the so-called penny press, cheap newspapers that catered to the middle and lower classes, the decades before the Civil War were a petri dish for such memes. It was a great time for persuasion through volume: lots of voters, lots of newspapers to argue in, and lots of ideas that may or may not be true.

and B) the growth of the so-called penny press, cheap newspapers that catered to the middle and lower classes, the decades before the Civil War were a petri dish for such memes. It was a great time for persuasion through volume: lots of voters, lots of newspapers to argue in, and lots of ideas that may or may not be true.

Does that sound familiar? It may only be another coincidence that the sudden growth of internet connectivity and discourse—a penny press for us if ever there will be one—coincides with a period of great fractiousness in our politics. But few would deny that there are a lot of questionable ideas out there. In the same way that a trilobite is useful to an exterminator, the primitive meme “slaves are happy” provides us with an instructively simple species of the genus “argumentative premise, absurd.” I submit that it shares with its modern descendants two key morphologies:

1) It is difficult for most people to verify firsthand, and

2) One side of an argument has incentive to believe it.

We see these same traits in such memes as “health care reform creates death panels” and “global warming isn’t real.” Ordinary people cannot investigate those claims for themselves without reading a 900-page report and getting a PhD in climatology, respectively, and those who advance them would be much better people if only they were true. And after all, you probably can’t say conclusively that they aren’t. For both claimant and auditor, the viability of the meme turns on doubt. The majority of people who ultimately make decisions based on these “facts” can’t really know if they are true—but yet they must decide, so they are forced to acknowledge that you can’t know everything. In this sliver of unlimitable possibility, the slaves have their dance party.

A perfect example of this is the current situation with the nuclear reactor in Japan. The obvious experts are nuclear plant engineers who design and maintain these reactors. From what I have read on the subject, most of these engineers agree there is not likely to be a dangerous exposure of radiation to the public, but it is hard for a layman to believe them because their jobs depend on nuclear energy being considered a safe source of power. In the end though, you should trust the experts, mostly because most of them put a lot of stock in their own credibility and the ones that don’t are checked by the others.

The trouble with trusting “experts” is that they can have political agendas as well. There are more than a handful of climate scientists willing to go on record saying that global warming is not a threat, that the oil spill in the gulf of Mexico won’t happen because the drilling platform is safe/is low volume and not much of a threat/will be easily controllable as soon as we get this cap in place, etc.

Experts are humans too, and as such are fallible… thus they can be incorrect, or worse, coerced by money and power.

Better than implicitly trusting experts is to not base your beliefs on anything which cannot be empirically proven, and confirm what proof is put forth for yourself. Death panels? Prove it. You don’t have to read the whole 900 page report, just the 2 or 3 pages cited by those stating that death panels are part of the legislation. Surprise, only a crass and intentional misreading of the section could possibly lead one to believe in death panels. Global warming? Carbon dioxide/methane/water vapor absorbs and re-emits infrared radiation. This is 5th grade science. Humans have been dumping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere in incredible amounts. This is readily verified and all but the most backwards global warming denier will concede this. Exactly how this will affect the weather patterns and agriculture in Nova Scotia fifty years from now is the part that the experts divine and then disagree upon.

The experts are paid to come to the conclusions and do the fancy math, but the data that they work with is usually pretty simple to access and understand for all but the laziest and/or most dimwitted “layman.” The problem is not one of epistemology, but rather one of the quantity and quality of dimwittedness.

TL;DR people believe stupid shit because they’re stupid, and politicians claim to believe stupid shit because it gets them re-elected.

Coda to the above: the difference between internets and penny newspapers is that the internets provide access to exponentially more information.

It’s like comparing the library of congress’ digital collections to reader’s digest.

Maybe there’s something there, too much information is just as bewildering as not enough…?

interesting, Danger.

Why, then, are people so stupid? This seems to me to be the inverse of what should be happening: we should, as a species, be getting collectively smarter. But maybe there’s something about the Internet that makes people dumb, or at least gullible. Maybe it’s an overload of evidence for both sides, and people can’t separate the bad information from the good. Look at the Obama birther issue. I just watched The Donald ask to see Obama’s birth certificate on The View – and not one of the knucklehead hosts bothered to mention that it’s already been published on-line, months ago. But still the issue exists simply because of the vast echo chamber that is the Internet and the fact that, if you go looking for arguments against Obama on the Internet you’ll get 10 trillion hits about this issue and not a single argument against has been updated to reflect the fact that his birth certificate has been made public. Seems like the right wing understands that once you tell a lie, the Internet insures that it will live in some form forever. Like a vampire immune to sunlight, silver bullets and wooden stakes, you can never finally kill bad arguments once and for all. Do I need to mention the thousand jaded creationist arguments that have been refuted from every possible scientific angle but which are raised anew every time a creationist opens their mouth?

Smick, for your information: the birth certificate of Obama has been published on line, true! But what you fail to understand is that that was NOT a legal BC. It was completely bogus – If you were to use that bogus BC for anything in real life, they’ll throw you out and charge you with a crime! This is how bad people are: they don’t look behind the facts and just believe that the BC that was shown on the internet, was real. It was not real – it was FAKE!!! Please check your facts and then write down your story! You were the exact example of how people are being deceived!