If you want to understand the problem of false equivalence in political reporting, consider this article from the Wall Street Journal about new IRS rules governing the political activities of 501(c)4 nonprofit organizations. The designation is intended for social welfare organizations, but it also covers the NRA and a slough of Tea Party groups, whose primary contribution to social welfare is relentless advocacy for their own legislative and political interests. As the Journal puts it in the story’s second paragraph:

Rules proposed Tuesday could at once help to curb the explosion in political spending by nonprofit groups, such as conservative heavyweight Crossroads GPS and the liberal Priorities USA, while setting clearer standards that could help the government avoid future dust-ups with politically active nonprofit organizations.

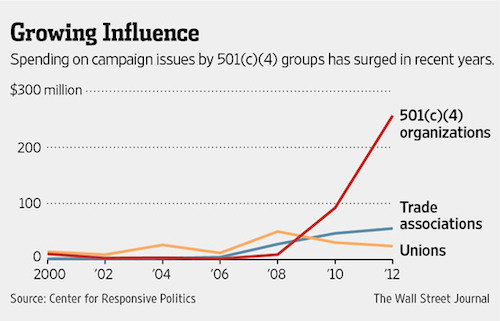

It sounds like Crossroads GPS and Priorities USA are two sides of the same dark-money coin, right? Except nine paragraphs later, we learn that Crossroads raised $180 million in 2011-2012, and Priorities raised $10.7 million.

The problem of political groups spending massive amounts of money on elections by passing themselves off as social welfare organizations is supposed to be a bipartisan issue. Really, Republican candidates benefit much more from dark money than Democratic candidates. This makes it difficult for the IRS to enforce 510(c)4 guidelines, since the agency’s reasonable interpretation is the GOP’s politically-motivated persecution.

Remember the IRS/Tea Party debacle of six months ago? Tea Party-affiliated 501(c)4 organizations said they were unfairly targeted by agency reviewers, ignoring the fact that they are obviously political groups. They have the word “party” right in the name, for Pete’s sake. Yet they mendaciously insisted that they were social welfare organizations, even going so far as to claim that handing out Romney door hangers was not a political activity.

Here lies the fundamental problem with the phrase “social welfare.” If you are sufficiently dishonest and/or crazy, “social welfare” covers pretty much anything. Even though the NRA is an advocacy group for firearms manufacturers and, according to conventional wisdom, the most powerful political lobby in the United States, it’s classed as a 501(c)4 organization for its Second Amendment-related civil rights advocacy.

It’s also an organization of people who like guns and believe they are good for society. Here is where crazy and dishonest meet, exchange a little money and fall in love.

Plenty of people believe that an armed populace is the best defense against tyranny, even when that means, say, arming schoolteachers so they can effectively kill school shooters. Misguided though that idea may be, many of the people advocating for it genuinely believe it would promote social welfare. Many other people believe that an armed populace is the best way to sell guns, and their claim to promote social welfare is purely cynical. How can the law distinguish between the two?

This problem is especially pronounced with regard to contemporary conservative organizations, who—unsupported conjecture ahead—tend to see less distinction between their political beliefs and what is good for society. If you believe that the number-one problem in America today is Barack Obama pushing us toward socialism, how can you pursue social welfare without engaging in political activity?

A self-aware political organization would be humble enough to acknowledge that politics is often a matter of opinion, and that a good society could exist according to something different from its own positions. I submit that such self-awareness and humility are precisely what is missing from contemporary politics, however, and they are in shorter supply on the conservative right.

That might explain why bipartisan groups like Public Citizen and former FEC official Bob Biersack are cautiously optimistic about the new IRS guidelines, while right-wing groups are incensed. For example, here’s a spokesman for the NRA:

At first glance, it appears like a blatant abuse of the tax code designed to muzzle the American people’s free speech rights.

A glance reveals so much. An honest reader would have a hard time arguing that the IRS plan to classify “communications that expressly advocate for a clearly identified political candidate or candidates of a political party” as political activity is a blatant abuse of the tax code. And even if the IRS made a list of organizations it wanted to disqualify from 501(c)4 status and then altered its rules accordingly, it would not muzzle those organizations’ free speech. It would only require them to pay taxes.

That’s maybe the most frustrating aspect of the free speech argument and, in a broader sense, the whole social welfare dodge. We’re not talking about denying these groups the right to advocate for and against candidates. We’re talking about denying that they are charities. Only the most mendacious or self-deluded could claim that the Ohio Liberty coalition is a social welfare organization and not a political group. Unfortunately, “mendacious and self-deluded” currently covers about half of the two-party system.

The WSJ article is behind a paywall.

It makes me sad every time you turn a two-sided problem into an argument against one side. “Really, Republican candidates benefit much more from dark money than Democratic candidates.” Don’t say that. The Nazis killed far more people than the Taliban have, but both groups are equally horrible. Republicans DO benefit more from these groups than Democrats. That doesn’t mean Democrats should be let off the hook. Moveon.org spending $50,000 for gun legislation is no better & no worse than the NRA spending $1million against it.

I’m not sure I follow your logic, here. If we agree that spending money to influence politics is bad — and I think we do — then both sides are bad for spending money to influence politics. But money is a scalable quantity, and I think it follows that spending more money is therefore worse. It may be wrong for a person to be able to give $250 to the candidate of his choice when many people can’t afford to do that, but I think it’s more wrong for that person to be able to give $250,000. That’s why I support limits on campaign contributions. I think that when we’re talking about the pernicious influence of money in politics, the amount of money is relevant.

I think I’ve got Justin’s back on this one. Exploiting an ethically dodgy loophole in the tax code for political gain is icky, and it doesn’t become more or less icky based on how much money you threw into that loophole. Just because the tools for exploiting it are scalable doesn’t necessarily mean the moral valence is, as well. Bad analogy: if someone engages in jury tampering through bribery, it doesn’t become less reprehensible if they can only afford to bribe two jurors instead of twelve. I’m very reluctant to use cash amounts as a measuring stick for moral action, particularly because it ends up parsing out morality into cash-like units, as though Priorities were $170 million more moral than Crossroads.