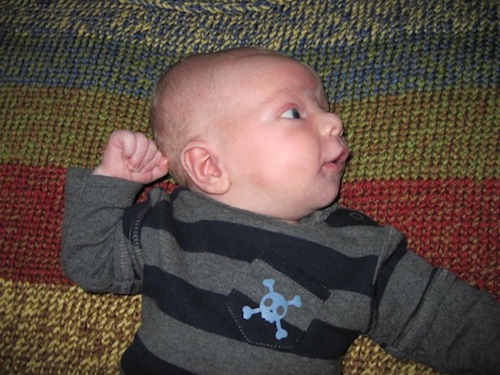

So I got him this skull-and-crossbones onesie because, you know, he likes that kind of thing. He's always been kind of alternative, kind of positioning himself against society, and of course it's a good memento mori.

Another Brooklyn bar bans babies, and—except for the headline writers at the New York Post, who are thrashing in their isolation tanks with glee at the alliteration—polite society girds itself in anticipation of another bitter argument. Nothing makes us angry like a baby. On Thanksgiving day, you can grab the turkey and make it dance around your friend’s kitchen like a puppet, have it drink a whiskey and tell a series of bone-and-breast jokes to his wife, then throw it back in the oven without even rinsing it off and be lauded as a great wit. But do the same thing with his baby and suddenly you’re a monster. A baby is like a pack-a-day smoking habit, turning friends against friends and making bars, funerals and other usual places of agreement into sites of bitter controversy. Ever since Brooklyn’s Union Hall unsuccessfully tried to ban strollers—and made the New York Times, thereby elevating the whole issue to the status of Real Thing That Is Happening—public drinking in America has fixed on one question: Should babies be the unwanted center of everyone’s lives? Or just their parents’?