I still remember the day that I, a boy-child of 14, encountered Robert’s Rules of Order. Oh, I though to myself. Here is finally the thing I like least in the world. As a set of rules for meetings, parliamentary procedure is boring squared. Even in the most interesting kinds of meetings—the Machiavellian ones where everyone pretends not to hate one another’s goals—procedure is at best a synopsis of a plot. It is therefore maybe hard to get psyched about the possibility of today’s Senate changing the rules of the filibuster, an instrument that the world’s greatest deliberative body abuses now more than ever.

But psyched you should be, dudes. Under present rules, Senators have six opportunities to filibuster any given piece of business, and they don’t have to speak or be present to do so. This practice has made the 60-vote supermajority a de facto requirement for even such mundane procedures as executive branch nominations, and is is ripe for abuse. Richard Shelby (R-AL) demonstrated as much in 2010, when he issued a “blanket hold” on approximately 70 nominees in order to leverage $85 billion in earmark spending for his home state.

As a body based on comity, the Senate is designed to grind to a halt at the strident objection of one member. It was also designed in the 18th century, when stridence was rarer and objection required some personal investment. When the Framers were framing, the Senate had less controversial business to entangle its regular business, and political parties did not really exist. The idea that a bloc of senators might look for opportunities to hold up the body was unthinkable, in part because the blocs had not coalesced.

Neither had they been given email. Shelby’s 70 holds, which left vacant 70 offices in the federal government, required only that he draft a memo expressing his intention to filibuster “all executive nominations on the Senate calendar.” He did not even need to remain in the chamber to interfere with its business. Under these circumstances, the people of Alabama essentially invested a man with veto power over one house of Congress—and sent him there to negotiate with 99 other men holding the same option.

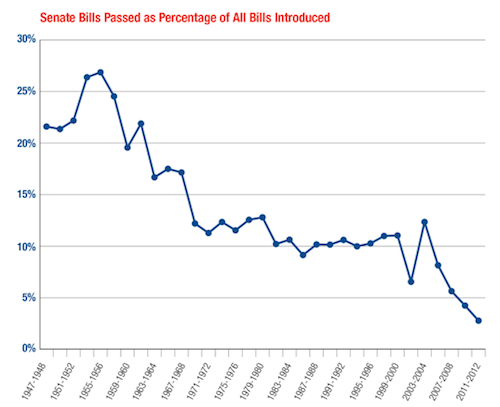

Of course, we have been doing that forever. It was less a problem in the past thanks to comity, the magical principle that insists senators act nicely toward one another and look for agreement most of the time. Comity was once a stronger force than it is now. That statement should sound the declinism alarm in your head. It’s the kind of nowadays complaint people of all eras make idly, but here it is, active, in graph form:

The astute observer will notice a trough shortly after the inauguration of George W. Bush. In June of 2001, Senator Jim Jeffords left the Reupblican party to caucus with Democrats, giving them a single-seat majority. Comity did not ensue. During that time, Democrats used the filibuster to thwart the president and his party almost as ruthlessly as present-day Republicans.

The memory of that time is causing older Democrats to hesitate now. Their argument is not so much that the filibuster resists abuse as it is that they will probably want to abuse it again later. That is a political argument, stemming from the same political myopia that impedes the Senate now. The American people do not have an interest in ensuring that the parties take turns exploiting a broken government.

The reform before the Senate today is modest: the only change under serious consideration would require senators to actually speak for the duration of their filibusters. That is not too much to ask to stop an unjust law or a corrupt nominee—situations that the filibuster was intended to address. It would probably make it too much for any Richard Shelby to wield the filibuster as a weapon of extortion. Such a change would make the filibuster an action again, rather than a gesture.

It would also make a narrow majority stronger and encourage the Senate to, you know, do stuff. An active Senate is precisely the scenario the Framers wanted to avoid, and we should be careful when we increase its vigor. But we are already in a scenario the Framers wanted to avoid—entrenched parties aggressively thwart federal business for political gain. The worst-case scenario is here. We should take the opportunity to adapt to it, because we are living here either way.

For anyone interested in a little more on the history of the filibuster or confirmation that D.Brooks isn’t make this shit up, I invite you to the entertaining NPR Planet Money podcast: http://www.npr.org/blogs/money/2012/12/11/166993494/episode-422-schoolhouse-rock-is-a-lie-or-how-the-filibuster-ate-washington