Ben al-Fowlkes sent me this excellent essay by Tim Kreider, in which the former political cartoonist notes how much more dangerous art seems to be for Islamists and North Koreans than it is for anyone in the West. That’s good: most of the reason we’re not afraid of art is that our civil society is stable and well-developed, and we’re confident enough in our ideologies that we don’t have to silence anyone who suggests they’re flawed. But part of it, as Kreider points out, is that contemporary Western culture has made art frivolous and anodyne:

“In the mature democracies of the West, there’s no longer any need for purges or fatwas or book-burnings. Why waste bullets shooting artists when you can just not pay them? Why bother banning books when nobody reads anyway, and the national literature is so provincial, insular and narcissistic it poses no troublesome questions?”

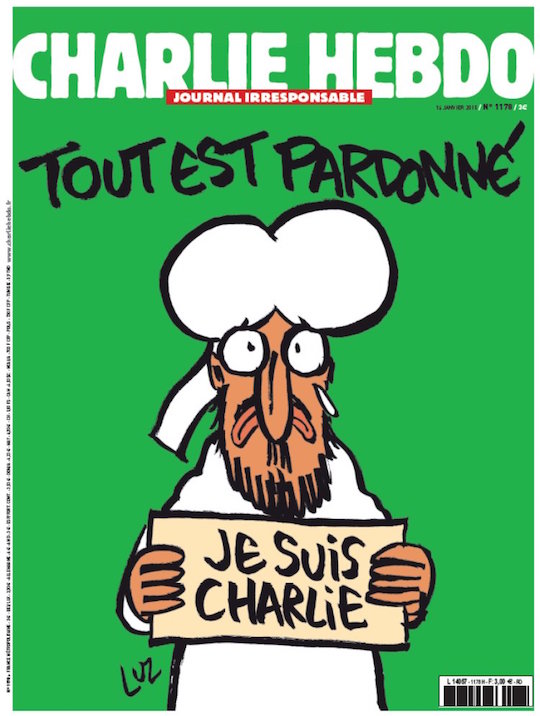

Kreider is good at the relieved lament, and he finds in the international outrage at the Charlie Hebdo attacks “a small, irrational twinge of guilt that we’re not doing anything worth shooting us over.”

He’s right, of course. Over the last week, the West has been united not only in outrage at the attack on a vaguely racist French cartoon magazine, but also in self-congratulation that we don’t kill people over art. Why would we, when art has been so thoroughly neutered? We act as if our resistance to any kind of censorship testifies to how much we value expression, but maybe we don’t restrict speech for the same reason Bedouin nomads don’t build dams.

Socially problematic art just doesn’t come up that often. Scolds fret about rap or violent movies, and these are legitimate symptoms or even causes of an unhealthy culture—but they do not threaten the established order in any meaningful way. Kreider cites the work of Thomas Nast against Boss Tweed as the last time a cartoonist genuinely upset anything in America. It’s not that we face a shortage of corrupt people in powerful positions. It’s that such people need neither law nor violence to marginalize art in a system that does that for them.

Let’s say Rudolph Giuliani has become mayor for life via a deal with Nosferatu and JP Morgan Chase, and now it’s time for him to give back to his supporters. He could make it illegal to mock vampires and financial services in a public forum, but that would look bad. People would say R. Giuliani was a tyrant.1 His city would contravene America’s commitment to free speech.

Alternatively, Giuliani could lift rent controls, cut taxes on capital gains income and imported boxes of Transylvanian earth, and generally help the cultural capital of the United States become too expensive for writers and artists to live there. This plan would achieve the same effect—no one in New York can make dangerous art and survive—without resorting to direct coercion. The mechanism tamping down expression would work just as well, but it would be lauded as improvements to quality of life rather than lambasted as censorship.

Of course, this hypothetical only makes sense in a culture that believes quality of life is improving even as meaningful art disappears. We live in that culture. The art we value is entertainment, and any government that knows what it’s about considers entertainment an ally, not a threat. Since at least the 1960s, when a generation conducted its revolution by buying Rolling Stones records, we have operated a system that makes art inert.

That we didn’t do it on purpose is a testament to our essential niceness, but it doesn’t mean we value free expression. It means we find expression sufficiently nonthreatening to tolerate. That’s fine. “As systems of oppression go,” Kreider notes, “this is definitely the one you want to suffer under.” But in our righteous indignation at the attacks on Charlie Hebdo, we should probably not pretend that we are champions of meaningful art. We are at best friendly acquaintances, willing to live with art so long as it keeps to itself.

As a political cartoonist, Kreider may have a distorted idea of what art is for. He seems to think that the only way for art to matter is to have some effect on politics or change what he calls the real world. That’s okay as long as we’re talking about political art specifically. But I wonder if any of the art you and he lament the loss of here was ever any good. Political cartoons may be interesting as speech, but as art they pretty much suck. That goes for political art in general.