Slate is midway through what is threatened to be a two-week series on income inequality in America, just in time for the controversial announcement that the President will not try to solve the economy by giving more money to rich people. Timothy Noah looks at several putative dangers to America’s middle class, including immigration, racism/sexism, and computers, none of which accounts for the growing gap between rich and poor in the United States. That gap is enormous. Currently, the wealthiest 1% of Americans take home 24% of the national income. Between 1980 and 2005, more than 80% of the nation’s considerable increase in earnings went to that 1%. To put that in perspective, back in 1915—the era of the Carnegies, Vanderbilts and Rockefellers, as well as a generation of non name-brand robber barons—the top 1% only got 18%. Economically, ours is a less equal America than that of our great grandparents.

It’s also a more generally successful one, obviously. The median income in 1915 was $687 a year—about $15,000 in today’s dollars, if you use the Consumer Price Index to adjust. Then again, if you adjust using relative share of GDP, it’s the equivalent of $253,000 a year. While the vast majority of us are making a lot more money than our World War I-era counterparts, the share of the national pie given to the average worker in 1915 would put him in the highest tax bracket in the United States today.

So the country’s resources are now more concentrated among a smaller portion of the population than at any time since we started measuring such things—except for in 1929, which was not an ominous year at the time. Is that bad? My sense of fairness is wounded by the knowledge that the rich are richer now than ever before, but it’s salved by knowing that questionably employed freelance writers are now richer than ever, too. If the pie has three times more cherries in it—to strain a metaphor—what does it matter that it’s not being sliced evenly?

For one, it makes it more likely that America will gradually develop an aristocracy. By “gradually,” I mean “pretty much already.” The richest 2% of American households make more than $250,000 a year, which is the kind of money that you don’t spend. The wealthy save a higher percentage of their income than any other socioeconomic group, which means that the most likely way for that money to get back into the economy is not through investment, research or wages but childbirth.

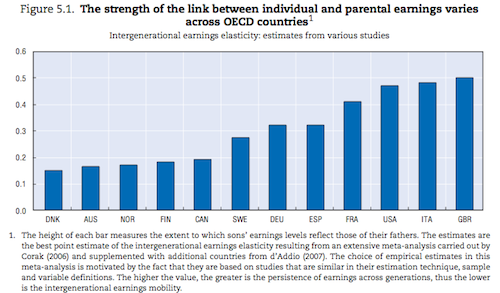

Rich people have rich children, who in turn get good nutrition, go to good schools, associate with good (read: rich) people and eventually get good jobs. That’s hardly an immoral system, but as wealth becomes concentrated it begins to work against the social mobility on which the United States prides itself. As this boring study that I don’t expect you to read discovered, America is not necessarily the beacon of opportunity we think it is. The following graph shows the comparative strength of correlation between fathers’ incomes and that of their sons in several postindustrial economies:

The good news is that America still offers more social mobility than Italy and Great Britain. Unfortunately, it’s easier to work your way up (or down) the economic ladder in Canada, Australia and Germany, as well as in such bleak socialist dystopias as Denmark, Norway and Sweden.

Of course, the Danes don’t have as many billionaires as we do. On the other hand, the Danes don’t have as many billionaires as we do. The peculiar concentration that gives to 1% of the nation’s populace a quarter of the nation’s resources every year has another pernicious effect, which I am going to call disparity between democratic and economic power.

Our rich people are rich as shit, but there are very few of them. To extend our already strained outrage at the recent debate over the Bush tax cuts: one would think that the question of whether to give a tax break to the wealthiest 2% of Americans would be a clearcut issue of public opinion. In a perfect democracy laboring under our current concerns, I think the vote would be about 98% to 2%.

In practice, things are not so simple. One reason such a large number of Americans have adopted political positions perfectly counter to their own interest may be the inordinate discrepancy, in the United States, between numerical and economic power. With a quarter of the money in the hands of a hundredth of the people, our democracy is bound to work on some principles besides the common will. Whether that means we’re also outside the common good is another question. It should at least be asked, if for no other reason than we are less equal now than we have been in a hundred years.

Is posting disabled? My comment isn’t appearing….

Oh here we go. I had to switch some html brackets into regular parenthesis.

I feel like the elephant in the room is ideology. People have it. And sometimes it prevents them from voting solely for whatever would economically benefit them the most.

For instance, our educational system informs people’s views of things like “socialism” and “freedom.” As a product of the American system, I have some value for the American experiment which, more or less, was designed to give a very free reign to people without the government stealing their shit. So already, there seems to be something wrong about telling the government to pick on rich people because they are successful, even if I stood to gain by shaking out the 2%’s pockets. When you couple that with the can-do, rugged, individualistic American myth, I have every reason to reject that the government, after confiscating wealth from people who earned it, should redistribute it to lazy people who haven’t. That’s unamerican, and the foundation of my beliefs are likely linked to American values (since I was educated in American institutions).

But all that is known to the readers and writers of Combatblog. What may be more interesting to examine is what the consequences would be for the 98% if they stopped voting “counter to their interests.” Tell the 2% we’re gonna tax the fuck out of you, because that’s to our benefit. Don’t the extremely mobile 2% just go “okay, we’re moving to (state which doesn’t discriminate against the wealthy),” and leave us with 0% of their tax income? It’s not as if the wealthiest 2% aren’t also pretty smart, worthwhile people we’d like to have around since they do more than watch Dancing with the Stars.

Happy you looked and opined.

You make a good point, Charlie, and I think it’s predicated on how we all want America to be: a place where hard work and ingenuity are rewarded, generally with money. Part of the problem with the concentration of wealth in a capitalist system, though, is that many of the ways rich people get money do not resemble what you or I would call “work.” As private fortunes grow, inheritance, capital gains, and other mechanisms by which the money system divorces profit from effort account for an increasing portion of our national wealth. While it’s morally repugnant to separate a doctor from the fruits of his practice, it seems a little more hazy to separate a millionaire playboy from the fruits of his father’s Dow Chemical shares.

That’s kind of a straw man, though, since we’re not talking about wealth—we’re talking about income. To your sound moral argument I can only counterpose a not-universally-accepted moral axiom: the well-paid person takes a greater benefit from our having an orderly, successful society than does the poor person. A person’s interest in maintaining a fun and stable America grows geometrically with income, so his share of the maintenance cost should be not just arithmetically (a percentage of his higher income) but geometrically (a higher percentage of his higher income) larger.

Again, depending on how you feel about that moral proposition, heavy taxation of the rich is either an instrument of fairness or a kind of extortion. My formulation could be seen as the rabble use the threat of riot to get food stamps and Pell grants and stuff. But I’m going to say that all the best contemporary aristocracies resemble hostage situations, anyway.

When I saw this website having remarkable featured YouTube movies, I decided to watch out these all video lessons.

Can you tell us more about this? I’d love to find out some additional information.