Slate runs three kinds of articles: (1) timely analyses of news items that appeared on Gawker four days ago, (2) Would This Statement Attract More Readers As a Question?, and (3) essays on subjects that the author happens to have just published a book about. For my money, category (3) is the most interesting, since if there’s one thing I like more than reading a book, it’s talking about a book I haven’t read. I was therefore thrilled to encounter Daniel Akst’s report/essay/plug about precommitment devices—not because it’s tremendously insightful or fun, but because it draws attention to two important issues facing society: Jean-Paul Sartre’s construction of vertigo and Eva Longoria.

Akst defines a precommitment device as any technique that a person employs now to help him choose a preferred option at some point in the future. He cites certain devices sold by Progressive auto insurance that monitor sudden accelerations, abrupt stops, and other indicators of risky driving. Policyholders who opt to have the devices installed and don’t drive like sophomores on lunch break get reduced premiums; they also get a means of ensuring that the choices they make in the cold light of reason, sitting in the insurance office and thinking about the importance of risk management, are the same choices they make when they’re running late for pilates.

A precommitment device is designed to overcome a fundamental problem of human will, which is that it is both free and temporal. I can do whatever I want, as everyone at Golden Corral knows, but that also means I can change my mind at any time. How, then, can I meaningfully do whatever I want? I want to become a doctor now, but midway through medical school I might suddenly devote my life to dance. I decide to quit smoking today, but as soon as someone offers me a cigarette, I decide that what I really want to do is quit smoking tomorrow. Halfway to the filter, I’m back to wanting to quit again, and the question of who exactly is in charge looks depressingly complicated.

Sartre identified this problem in Being and Nothingness during his metaphorical discussion of vertigo. The vertigo you feel when walking along a narrow mountain path, Sartre says, is the fear not that you will fall but that you will suddenly decide to step off the edge. The absoluteness of our freedom is such that we may act in any way at any time, and this becomes the freedom to thwart our own desires. Because any choice by definition involves a gap in time between when we choose and when we act on that choice, we open a window through which our future selves can climb, fire up the XBox and render our present will meaningless.

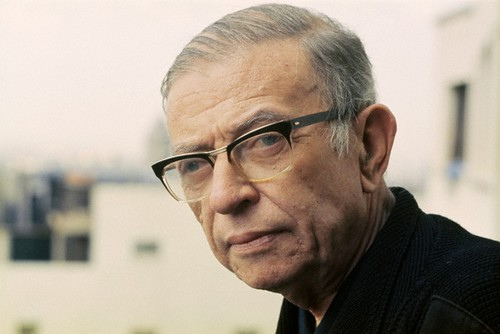

The precommitment device solves this problem when it works, but it paradoxically works by limiting our ability to choose. Present Dan, having been screwed over by Past Dan time and again but finding himself unable to reach him, decides to take his revenge on Future Dan instead by flushing all the cigarettes down the toilet. Future Dan is thereby robbed of his freedom re: cigarettes, and when he becomes Present Dan he will not be able to choose according to his will; instead he is forced to submit himself to the choice of Past Dan.* ![]() Whether this constitutes a triumph of the will or an abridging of it depends on which Dan you consider real.

Whether this constitutes a triumph of the will or an abridging of it depends on which Dan you consider real.

So it’s a can of worms, and it writhes even more disturbingly as we invent new ways to be free—that is, to break with the determinations of the past. Consider Eva Longoria. She recently divorced her former husband, San Antonio Spur Tony Parker. Shortly thereafter, she appeared to have removed the tattoo on her wrist that commemorated their wedding date. First of all, there is a whole segment of people who do not consider numbers tattooed on the wrist tremendously romantic. Second of all, Longoria’s tattoo was a classic precommitment device. If it did not commit her to staying married to Tony Parker, exactly, it at least forced her to remember their wedding date whenever she looked at her lithe, torso-disporportionate wrist.

Except she paid a doctor to shoot it off with a laser. Thus a freedom of the present—the freedom to remove tattoos, which were permanent before we invented medical lasers—abridges a freedom of the past. One hundred years ago, Eva Longoria would have had to live with her 7/7/07 tattoo even after Tony Parker became her reviled first husband, and it would have developed a new meaning whenever she looked at it—perhaps one connected to the transience of desire or the person she had become in the intervening years. But now it’s just gone. Eva Longoria has escaped her past, and in doing so, Future Eva has escaped the will of Past Eva. Past Eva’s freedom has been, strangely, obliterated. Whether this constitutes a triumph of the will or an abridging of it depends on which time you consider real.

It’s Existential Monday, everybody!

Why is this not a recurring segment on Combat!? Seriously.

This is very fascinating, You’re an overly skilled blogger.

I have joined your rss feed and look ahead to in search of more of

your wonderful post. Additionally, I have shared your website in my social networks