It’s a new year, and that means we’re incrementally closer to a terrifying future only imaginable to our grandchildren, whose brains will have much more highly-evolved nightmare centers. Or not—it depends on how the economy shakes out. In Europe, where the economy has been shaking out into a fine dust since the Marshall Plan, things are not looking so good. A few weeks ago, we discussed student riots in Britain over proposed hikes in university tuition. Yesterday, the New York Times ran this story containing the quote in our headline, in which Italy’s Francesca Esposito—who totally knows where to get ecstasy, by the way, but does not want to meet you at your hostel—laments her position as a 29 year-old penta-ligual with master’s and law degrees who can’t find a paying job. Instead, she works as an unpaid “legal trainee” for the Italian government—in their social security administration, no less. Like a lot of young people in southern Europe, Esposito gets paid in irony, and she’s pissed.

Youth unemployment runs about 40% in Spain and 28% in Italy. Like Greece, both countries have large cadres of middle-aged and senior-citizen workers that make it difficult for younger people to find jobs while they remain in the workforce and pose a looming pension crisis when they retire. The Times story is full of highly-educated Europeans in their late twenties and early thirties who have never found paying work, even as austerity measures further straiten the job market in response to the social security costs their unemployed asses can’t cover.

Hence the rioting. “By now,” economist and former Italian prime minister Giuliano Amato said, “only a few people refuse to understand that youth protests aren’t a protest against the university reform, but against a general situation in which the older generations have eaten the future of the younger ones.” As Europe’s birth rate declines, older workers cling to their jobs, and large voting blocs of pensioners aggressively protect their social security funds, the best-educated generation in the continent’s history languishes in a protracted, economically-enforced adolescence. Those who enter the workforce do so as unpaid interns or settle for underemployment in a labor market where the most lucrative jobs available pay less than $1,000 a month. “They call us the lost generation,” Coral Herrera Goméz, a 33 year-old with a PhD, told the Times. “I’m not young, but I’m not an adult with a job, either.”

Sound familiar? Europe’s pension and youth employment problems differ from our own not so much in kind but in degree. Of course, that degree is significant. The American economy is more robust than that of southern Europe in roughly the same way that Metallica is more robust than the Scorpions, and our social welfare system is not so gargantuan. And of course, we live in the land of opportunity, where we don’t have to contend with what the Times described as “a corrosive lack of meritocracy.” Life in Europe may be all about who got there first, but here in America, we have a little something called social mobility. It’s right there next to the ketchup, Francois.

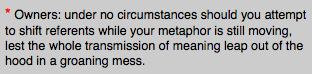

Or maybe somebody used it all up and put the empty carton back in the fridge.* According to the Center for American Progress, the United States now has one of the lowest rates of economic mobility of any wealthy nation. Only in Britain does a son’s expected income correlate more strongly with his father’s. It turns out that kids born in the bottom quintile of incomes stand a much better chance of making it to the top quintile in Denmark than they do in the United States. Again, we have a stronger economy and a significantly lower unemployment rate, so our situation barely compares to that of southern Europe. Still, the possibility that a large cadre of entrenched older Americans has locked up much of the nation’s wealth and resources presents a looming threat.

According to the Center for American Progress, the United States now has one of the lowest rates of economic mobility of any wealthy nation. Only in Britain does a son’s expected income correlate more strongly with his father’s. It turns out that kids born in the bottom quintile of incomes stand a much better chance of making it to the top quintile in Denmark than they do in the United States. Again, we have a stronger economy and a significantly lower unemployment rate, so our situation barely compares to that of southern Europe. Still, the possibility that a large cadre of entrenched older Americans has locked up much of the nation’s wealth and resources presents a looming threat.

Fortunately, we don’t face Europe’s debt problems, even if we do suffer from a similar generational imbalance. That’s why we could afford to enact $700 billion in unfunded tax cuts last month—including cuts for the very richest 10%—and why politicians of every stripe agree that no matter how bad things get, we’ll never reduce Social Security payments. Heck, we can even spend the Social Security Trust. We’ll just pay as we go, and as long as each successive generation is larger than the one that came before, the numbers will work themselves out. Oh. Um, we all have to make sacrifices, land of opportunity, at least you don’t live in Europe.