Both the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal ran stories about the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court this week, and I urge you to read them. The FISC, which the Times insists on calling the “FISA court” after the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, has established a body of case law that significantly expands the federal government’s domestic surveillance powers, and it’s all secret. You’re not allowed to know what the FISC determines the NSA and FBI can legally do, because that would help terrorists. In June, when the Senate asked NSA director Gen. Keith Alexander whether FISC would ever make some of its rulings public, Alexander said:

I don’t want to jeopardize the security of Americans by making a mistake in saying, ‘Yes, we’re going to do all that.’

So “no,” then? Here’s a link to Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language,” just in case Gen. Alexander is reading this. We know someone in his office is.

We will have to take the general’s word for it that knowing certain things about the American legal system would jeopardize our security. Surely, security is not a word he would use simply as a shibboleth for authority. You can’t just throw security around, particularly in areas related to interpreting the law, where every word counts.

Take the word relevant, for example. According to the Journal story, FISC authorized the NSA to collect records of millions of Americans’ phone calls based on its interpretation of the Patriot Act, which allows government agencies to demand information that is “relevant to an authorized investigation” into international terrorism or foreign intelligence.

Apparently we are all relevant to an authorized investigation, which I assume investigates the question “who is a terrorist?” Mark Eckenwiler, until December the Justice Department’s authority on criminal surveillance law, describes FISC’s interpretation of relevant as meaning everything, in what he calls a “stretch” of previous legal interpretations. While relevance has always been applied broadly in criminal law, the word must surely preclude something—say, for example, information on all Americans.

We don’t know how the Patriot Act is being interpreted by courts, however, because all of FISC’s rulings are secret. The court does not hear from attorneys who argue against the government’s position, nor does it allow non-government witnesses. There is no adversarial system in the FISA courts, but the judges who serve insist that FISC is not merely a rubber stamp for NSA and FBI requests.

Meanwhile, according to the court, FISC heard approximately 1,800 requests for surveillance data last year. None of them was denied. There is a word for the kind of court that meets in secret and finds for the government 100% of the time, and it rhymes with schmangaroo. Given that FISC approves every request for surveillance and keeps secret its justifications for doing so, a cynic or a phenomenologist might ask what the difference is between FISC and no oversight at all.

Being told that the secret court has a well-argued reason why the secret government program that appears to violate the Fourth Amendment is just fine is, from an ordinary American’s standpoint, not materially better than simply being told to shut up. I’m sure it’s perfectly legal that the government is monitoring my phone and internet use, but I would like to read the opinion. It’s not enough to know that the opinion is out there, or that it’s all for my own good, because that is what an irresponsible government says, too.

The US government may or may not be irresponsible, but the secrecy of FISC makes it unresponsive. As Ezra Klein points out in Wonkbook, the Patriot Act is a law passed via democratic channels. Normally when the American people pass a law through our representatives, we also have a chance to see how that law is implemented and interpreted by the courts. If it sucks—if, for example, it inadvertently authorizes the NSA to spy on American citizens—we usually get to see that and work the levers of representative government accordingly.

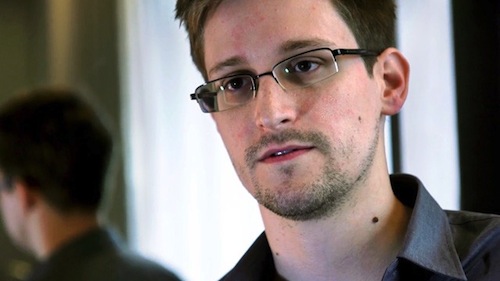

In the case of the Patriot Act, we don’t get to see what the law does. We caught a glimpse thanks to a leaker who is now an international fugitive. The Patriot Act’s very name implies deception, and its implementation has resulted in unprecedented spying on and secrecy from the American people. We cannot know if it is being abused, because the federal government refuses to tell us what it thinks it means. The rule of law means nothing if we do not know the law. A court means nothing if we do not know how it rules.

I think it’s a disingenuous argument to suggest that FISC proceedings need more public scrutiny. Scrutiny of the uninformed is worse than none. This is a running theme on Combat blog known as “the problem of others.” Moreover, if that information was available, no one would really give a shit. The ACLU might, but collectively, no one would give a shit, and I wager that demonstrates the degree to which we really don’t believe evil is afoot. Collectively, we actually realize this data mining will have no real impact on our lives, and we’re only angry because it is our identity to be angry about these kinds of things.

That long lesson in the difference between professed and practiced values called high school encourages us to parrot back revolutionary sentiment thoughtlessly. And like high schoolers, we demonstrate a small capacity for considering real world impacts when we do so. This fear of legally sanctioned NSA programming is no different than the irrational revolutionary attachment to the 2nd amendment. I think you would understand we would still be Americans with stricter gun control, and I would add we still have real privacy even when our metadata is on an additional couple servers to the thousand it already is.

I would argue this sentiment is a painful distraction from real problems. At the very least, it’s the kind of sentiment I would expect from my grandfather who has a historic and notional concept of the U.S., which he maintains by being bereft of contemporary knowledge. The knowledge that would inform this debate is that the information genie is out of the bottle, and we can’t put the cork in anymore. Just like children must learn life is not fair, Americans need to learn that their government uses data to make cost-effective decisions just like any business, and every day we’re on the internet and not a cabin in Montana we’re voting that we prefer to trade that information for the benefits it brings.

I think it’s a painful distraction to spend time addressing FISC when it is operating on law like the Patriot Act. If we could address the sociological conditions that enable a democracy to pass that kind of bullshit, we’d be better off. FISC secrecy is a symptom of a much greater threat to democracy, and that’s the political enabling of fear-based legislation.

When a law goes under the title “The Patriot Act”, learning about the FISC which operates because of it, becomes valuable. That’s how we move beyond “with us or agin’ us”, “keep you safe”, “or the terrorists will win”, and other slogans.

I, in fact, do give a shit about the details. As they say, that’s where the devil is.

You give a shit about the details, but you would not spend a week reading through case documents in order to determine whether a particular order is legal or not. Even if you did, you nutcase you, you would likely do a worse job than the current appointees who do legal work full time. And if you, Hirondelle, actually are a viable appointee to the FISC, then I mean to make the point about everyone other than you.

When we say we give a shit about the details, or want more scrutiny, really what we’re saying is we give a shit about details as summarized by NYTimes and want _someone_ to be doing oversight. Intrinsic to both of these is a level of trust, which is why I called this argument disingenuous. Is the FISC more fallable than the journalist behind an NYTimes article?

It’s an undergraduate point to make, but its easy to lose sight between the difference of a threat and a possible threat, just as here it’s easy to lose focus of the distinction between public scrutiny and scrutiny of small groups of people. A lot of scrutiny is handled by small groups and their decisions and rationale is not strictly public. The goings-on in the Google boardroom as well as in the IRS are all opaque to us. Yet some subjects hit our “anti-tyranny” trigger and suddenly we demand information be “public.” Well, fine, but the whole public won’t do anything with that information, and the parts that would will do as good or bad a job as the expert judicial administrators currently signing off in the FISC.

It is always a surprise when an argument is taken into the personal, replete with name calling.

I did say, after all, that I give a shit. I did not say that you are one, or that your opinion made you a “nutcase”. Reserving the right to disagree, without excoriation by someone with a different opinion, is the nature of

civilized public comment.

I have spent the last twenty years of weeks reading case documents, trying to determine either the legality of various laws or how they may be applied to the facts at hand. Some times I am found to be correct; and sometimes I am not. In the process, I’ve learned that reasonable people may disagree; and that name calling and telling people what they are “really” saying or thinking is counterproductive.