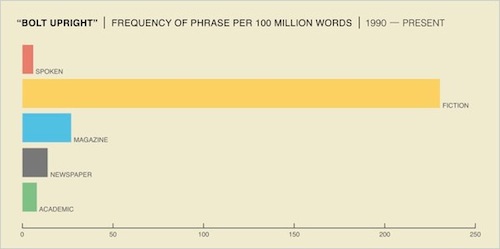

The graph above comes from this excellent New York Times article about the Corpus of Contemporary American English, a massive, searchable database of written and spoken language from the last 20 years. As you can see, people sit bolt upright in novels a lot more than they do in journalism or conversation, possibly because interviews rarely start with the subject waking up and possibly because contemporary fiction is more mannered than we think. There is a big difference between vernacular and prose, as anyone who has read Dostoevsky will tell you. People are always exclaiming and crying and saying darling! in 19th century novels—a cataclysm of melodramatic affectation that was supposedly fixed by the advent of modernism. Modern and postmodern fiction prides itself on writing the way people really talk. The work of George Saunders and David Foster Wallace is peppered with likes and neurotic digressions, and if it does not exactly capture how we speak now, it at least gets how we think we speak now. As a little fiddling with the COCA reveals, however, the gulf between lived experience and fiction remains as wide as ever.

The graph above comes from this excellent New York Times article about the Corpus of Contemporary American English, a massive, searchable database of written and spoken language from the last 20 years. As you can see, people sit bolt upright in novels a lot more than they do in journalism or conversation, possibly because interviews rarely start with the subject waking up and possibly because contemporary fiction is more mannered than we think. There is a big difference between vernacular and prose, as anyone who has read Dostoevsky will tell you. People are always exclaiming and crying and saying darling! in 19th century novels—a cataclysm of melodramatic affectation that was supposedly fixed by the advent of modernism. Modern and postmodern fiction prides itself on writing the way people really talk. The work of George Saunders and David Foster Wallace is peppered with likes and neurotic digressions, and if it does not exactly capture how we speak now, it at least gets how we think we speak now. As a little fiddling with the COCA reveals, however, the gulf between lived experience and fiction remains as wide as ever.

Consider that mainstay of literary fiction, the shrug. Characters is stories and novels shrug regularly, despite the relative infrequency of the gesture in real life. When we’re relating an anecdote at the bar, we rarely consider it important to mention when and how*![]() people shrugged, yet a quick COCA comparison suggests that it’s crucial to our written accounts. The ratio of “shrugged” in fiction to speech is 99.82 to 1. People in books shrug a hundred times more often than people in conversation. It’s an epidemic.

people shrugged, yet a quick COCA comparison suggests that it’s crucial to our written accounts. The ratio of “shrugged” in fiction to speech is 99.82 to 1. People in books shrug a hundred times more often than people in conversation. It’s an epidemic.

One plausible explanation is that the shrug is a particularly efficient gesture. Nothing conveys ambivalence like a shrug, unless it’s a much longer combination of meaningful actions and description. The COCA does not search for 800-word expressions of conflicting desires undergirded by the compulsion to appear nonchalant, so it’s likely that “shrugged” runs high because it’s an evocative thing to do. Yet it is worthwhile to consider what, exactly, the shrug evokes.

As any decent fiction workshop reminds us, there’s a difference between ambivalence and apathy. The first is the combination of conflicting desires, and it is the soul of psychological realism. The second is the absence of desire, which is pretty much verboten in modern narrative theory. Yet the shrug is the iconic gesture of apathy. You do it when you don’t care, not when you are torn by conflicting emotions. Hamlet does not creep up on the praying Claudius and shrug. Given its popularity in oblique dialogue—“I don’t know if two people can ever understood each other,” Linda shrugged—the shrug seems more like a pass than an action. It’s something people do when they’re not really doing anything, which should make it antithetical to fiction as we now understand it.

Modern storytelling thrives on volitional certainty—on people pursuing clear objectives that create strong conflicts. The COCA lists ratios near 1:1 for the appearance of the words “certain” and “sure” in fiction versus speech, probably because those words also function as a dead adjective and an expression of agreement, respectively. But a search for the phrase “knew he had to” yields a fiction-to-speech ratio of about 2:1. The more highfalutin “knew he must” goes off at 31:1, although the sample size is suspiciously small. It appears that fictional people have a clear sense of what they should do—and, by extension, how they feel about a given situation—far more often than real people.

And yet the shrug persists. Like the word “just,” it’s a prose gesture that seems to fit into almost any sentence. It could be that the shrug has become a tic of contemporary fiction, like like in contemporary speech. But it could also be that we have identified the wrong item as a trope of modern narrative.

Maybe it’s the shrug that is the genuine expression of human experience, and the clean objective is the affectation. The shrug is a naturalistic gesture that keeps breaking through the artifice of two people who know what they want—the vernacular action authors instinctively include when they’re trying to adhere to the convention of intentional behavior. “Constance, you mustn’t!” Harold cried. “I cannot bear to see you act so impertinently,” seems now like an obvious affectation, even though it was the height of naturalism in the 19th century. We scoff at the language, but perhaps the really fantastic element is the idea that someone could clearly know his own desires. Today we call our literature realism. Tomorrow, the elements of realistic fiction we consider most important might be regarded as the fluttering fans of a mannered age.

Request for tomorrow’s essay: Tell us what this all means for the work of Ayn Rand.

The concepts of “shrugging,” ‘realism,” “volitional certainty and clear objectives” are all orbiting around Rand, but I think it would make my brain hurt to figure it out (plus I’ve never read any of her books).

This is hardly surprising, is it? You’d find a similar chasm, for example, if you compared movies to real life. In movies, farts are funnier, explosions are prettier, and sex is less disgusting. It’s no surprise that interactions in fiction are more mannered or expressive; they exist for our entertainment. I wouldn’t have it any other way.

American English has a singular affectation of and obsession with “naturalistic” prose that we don’t see in other languages. When you study written French or Portuguese, for example, it’s openly assumed that you’re learning dialects different from their spoken versions — and written (“classical”) Arabic is, apparently, like a wholly separate language.

I shrugged at least 8 times reading this. Just trying it out rather than sincere shrugging. I felt a little like a puppet by the end. But I like the idea of Dan moving his various readers in this (literal) way.