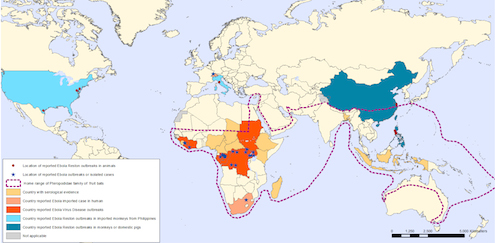

Don’t worry: the turquoise area on the map above only shows where the ebola virus has been found in monkeys imported from the Philippines. I don’t want to succumb to hysteria, but maybe the United States should refrain from importing Filipino monkeys for a while, just until this blood-exploding-through-people’s-skin thing blows over. Then again, that’s the same sort of correlation/causation thinking that has led villagers in Guinea and Liberia to bar aid workers from entering their communities. Where there’s ebola, there are doctors. Ergo, doctors must be causing ebola. Education is a public health issue, you guys.

For the record, you get ebola from a bat or from contact with the bodily fluids of an infected person, not from doctors. As the Times notes, some prominent aid workers were infected in the recent outbreak, but they are unlikely vectors because they generally protect themselves from exposing others. More problematic are the village leaders who, in their fear of aid workers, prevent the sick from getting treatment:

Workers and officials, blamed by panicked populations for spreading the virus, have been threatened with knives, stones and machetes, their vehicles sometimes surrounded by hostile mobs. Log barriers across narrow dirt roads block medical teams from reaching villages where the virus is suspected. Sick and dead villagers, cut off from help, are infecting others.

A lot of this stuff is happening in the Forest Region of Guinea, which the Times describes as “known for its belief in traditional religion.” That’s a nicer way to described African animist traditions than a lot of the terms we used to use. But another nice feature of the modern age, besides our respect for different ways of knowing, is our germ theory of disease. Here these two values come into conflict, in a way that is making a lot of people dead.

The developed world has an analog to this problem in the recent anti-vaccination movement. America is a free country, meaning that people are free to read the internet until they understand medicine better than their pediatricians. In exercising this freedom, however, parents who choose not to vaccinate their children endanger the health of strangers.

Outbreaks of disease are a classic instance of a collectivized cost to an individual choice. You may think that vaccines cause autism, because A) autism diagnoses and vaccination rates both went up as more children started seeing doctors, and B) you are dumb. From an individual perspective, you have the right to not get your kid vaccinated for measles because you regard your interpretation of Jenny McCarthy as superior to generations of medical consensus. But from a social perspective, your exercise of that right increases the likelihood that other kids will get measles.

So what we have here is a choice between two icky arguments. One is an argument against freedom: we should force people to vaccinate their kids and otherwise participate in public health initiatives, because they don’t understand epidemiology as well as we do and their ignorance is jeopardizing other lives. Or we have an argument against tolerating non-scientific ways of knowing: we should stamp out anecdotal reasoning and African animism, so that people use their freedom to make choices that are not destructively ironic, for example blaming doctors for ebola.

Both of these claims run counter to contemporary western values. We don’t want to indoctrinate the individual into an agreed-upon system of thinking, and we don’t want to force him to submit to medical care. These two values are not prima facie problematic when they come together, until such time as the individual adopts a destructive system of reasoning and lives in society with the rest of us.

That second part is the insoluble problem of pluralism. Insofar as doctors from the developed world are going to Guinea and treating animists with ebola, we live in the same society as Africans. Insofar as we fly monkeys from the Philippines to LA, ours is a single global culture. But it’s also a culture in which we respect differences, even divisions. At this point in human history, we share consequences globally, but we do not share a system for managing them.

Liberians who blame doctors for disease are an instance of how we live at a strange moment in our development. Two hundred years ago, whole villages could die of ebola without western doctors even knowing about it. Two hundred years from now, one hopes, African villagers will understand the germ theory of disease and act responsibly. For now, we live in interesting times.

Exploding monkeys isn’t the only thing we import.

Importing the rest of the worlds problems is a profitable industry for a percentage of us.

Did you hear that now california is expected to pony up to immunize a whooping cough epidemic that we’ve imported?

Because they’re poor and cant pay for anything themselves.

Some may be surprised by how affordable the

service is. If the inside of your car or truck needs some care, you are

in luck there, too. Sit on a lot of bikes to get a

feel of height and riding position.