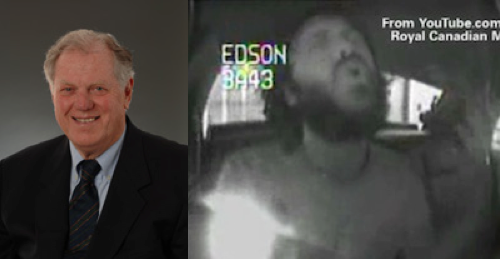

Charles Snelling, who killed his wife and then himself after Alzheimer's Disease concluded their 60-year marriage, and Robert Wilkinson, who sang "Bohemian Rhapsody" in the back of a squad car (at right)

With today’s post headline, Combat! blog abandons all hope of attracting a general audience. If you have read this far, you are animated by a loyalty that most of the internet simply does not possess. Tomorrow we’re changing the format to nothing but videos of cats falling into toilets,* so I figured we’d use today to consider the ontology of morals. On Friday, the New York Times ran what was perhaps the most approving murder-suicide story ever. Charles Snelling, who in December wrote an essay describing his six-decade marriage to Adrienne Snelling and the Alzheimer’s Disease that consumed her last five years, killed his wife and then shot himself. Also last week, the internet became enraptured by video of a drunk man singing Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody” in its entirety while locked in the back of a RCMP squad car. Everyone considered both these acts profound expressions of the human spirit.

so I figured we’d use today to consider the ontology of morals. On Friday, the New York Times ran what was perhaps the most approving murder-suicide story ever. Charles Snelling, who in December wrote an essay describing his six-decade marriage to Adrienne Snelling and the Alzheimer’s Disease that consumed her last five years, killed his wife and then shot himself. Also last week, the internet became enraptured by video of a drunk man singing Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody” in its entirety while locked in the back of a RCMP squad car. Everyone considered both these acts profound expressions of the human spirit.

I actually agree with everyone on these two counts, which offers a glimmer of hope that we might repair our relationship. It’s worth noting, however, that many conventional theories of morality fail to explain why Snelling’s murder-suicide and Wilkinson’s rhapsody qualify as good. That seems to indicate a failure in the theories and not the morality, because I would argue that most decent human beings viscerally recognize both actions as great.

There are plenty of rubrics under which they aren’t, of course. Judeo-Christian ethics, for example—which in addition to compassion bases most of its moral judgments on obedience to God—has traditionally frowned on killing your wife and then yourself even if you have a really good reason. Big-three religious morality heavily emphasizes sin, encouraging us to think of the ethics of action in negative terms. Sin is wrong regardless of circumstance, and the compassion implicit in Snelling’s act is overridden by the admonition that you never, ever kill yourself—or anybody else, unless they’re a Hittite or something. The moral act is first the one that violates none of God’s commandments, and second what helps somebody else.

The important thing in Judeo-Christian morality is obeying the rules, which is a nicer way to say not breaking them. The attempt to put morality in more positive terms is at the heart of Utilitarianism, which considers the ethics of actions in terms of how much happiness—used pretty much synonymously in this system with “good”—they bring to how many people. Within this scheme, Snelling’s murder of his wife was good, because it relieved her suffering when the rest of her existence was essentially meaningless.*  But his subsequent suicide—which ends the life of a person not debilitated by disease and deprives his family members of his non-demented companionship—balances the utility equation. At best, Snelling’s action is neutral. Utilitarianism is at a loss to explain the startling nobility of his behavior.

But his subsequent suicide—which ends the life of a person not debilitated by disease and deprives his family members of his non-demented companionship—balances the utility equation. At best, Snelling’s action is neutral. Utilitarianism is at a loss to explain the startling nobility of his behavior.

And both systems are completely mute when it comes to Wilkinson. His rendition of BoRhap helped no one and probably subjected his arresting officer to considerable irritation. Yet watching the video, one cannot help but like and—look deep, now—admire him. His behavior fits with no systematic construction of the good, from Plato to Jesus to John Stuart—oh snap, here we are at Nietzsche. In his insistence that true morality is constructed by the individual, Nietzsche articulates an expressive ethics that subsequent scholars have likened to aesthetics. What is moral for Nietzsche resembles what for previous generations has been beautiful—creative, changing with the times, and above all dependent on circumstance and execution.

The moral beauty of Wilkinson’s act is heavily dependent on the élan with which he commits it. If he had skipped the second verse or mumbled “Bohemian Rhapsody” to himself in the back of the car, his behavior would have been less commendable. Half of the good in what he did has to do with courage, a universally-admired quality conspicuously absent from most systematic theories of morality. That vocal performance was stunningly and unexpectedly the right action for that moment, and Wilkinson committed to it with what can only be called moral clarity.

The same aesthetic criteria of timing and style are even more important in Snelling’s act. It goes without saying that he would not be lauded for killing his wife and then himself after six months of marriage rather than 60 years. Equally obvious in significance is Adrienne’s condition; surely any moral system is flawed that prohibits you from killing me when I have lost my mind and can’t take care of myself. In absence of a dogmatic system that says otherwise, any decent person recognizes such an act as commendable.

Morality is a visceral sense first and a reasoned system second. That said, we get a lot of visceral senses that are immoral in the extreme. We need our understandings of virtue to be as nuanced as the situations we run into, because not everything is as clear as Snelling and Wilkinson. When we encounter acts that striking—particularly when they are so different—it’s worth our time to study them. Like Les Demoiselles D’Avignon or “Worker and Parasite,” they give us a glimpse of what goodness can be.

Wilkinson’s solo is happily noteworthy on two levels:

He doesn’t attack the Mountie by flinging himself or invectives against the wire separating him from the officer; and

The Mountie just lets him sing. (He might have received a “tune up” from some less disciplined law officers.)

This video was posted under the caption “Life’s Rich Pageant”.

That pretty much sums it up.

I didn’t read on for loyalty, I read on because I think morality is important. People like us do exist.

“That vocal performance was stunningly and unexpectedly the right action for that moment, and Wilkinson committed to it with what can only be called moral clarity.”

He was drunk.

Neither of these strike *me* as particularly beautiful. Does that make them morally wrong?

Both stories seem sad, understandable.

Also kinda boring. I couldn’t get through either the video or the Times essay that Snelling wrote.

Thanks for inducing me to watch that video. Props to him for refusing to admit he is drunk and also for the police for letting him finish once they pull into the garage.

In the US this dude gets a face full of pepper spray.

Awesome article. It’s nice to be compared to a suicide. Gives a guy something to think about.