Your boy Ben al-Fowlkes was about 90 pages into From Russia, With Love when he texted me to note that James Bond had not yet appeared. Pretty much the whole first act is about people who have been selected by the Soviet government to kill Bond. From Russia was the first 007 novel I read, so I wondered if this odd choice was a feature of the series. Maybe the whole gimmick was that Bond appeared as a kind of secondary character, or as the instrument that obliterates the people we meet in the first act. This conjecture was disproven, however, by Live and Let Die, which starts with Bond on page one and, except for short bouts of third-person omniscient, sticks with him throughout. L and Let D was also deeply weird, though, for its presentation of black Americans as a conspiracy along the lines of international communism. By “weird” I mean “racist.” Yet because it was Fleming’s second novel, and more of a crime story than a spy story, I wondered if maybe it, too, was an exception.

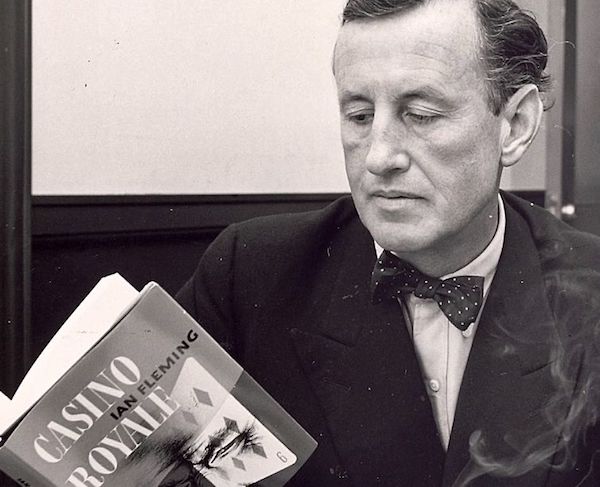

Now that I have read Casino Royale, the first novel in the 007 series, I feel more comfortable saying that they’re all weird. Casino Royal is weird similarly to Live and Let Die, in its deeply chauvinistic attitude toward women.1 Bond is enraged when he learns that he has been partnered with Vesper on his assignment to bankrupt French investor and Soviet agent Le Chiffre, and his first few interactions with her are larded with internal monologues about how damned emotional women are. Maybe that’s all just setup, though, for the melting of Bond’s heart that ensues after they (spoiler alert) get Le Chiffre.

I read this novel on Kindle, and Bond successfully completes his mission exactly 66% of the way through. The remaining third is devoted to his after-mission honeymoon with Vesper, which I will not spoil for the approximately one percent of you who are reading this post and plan to read the novel but have not seen the 2006 movie. It’s not just denouement. There’s a twist, but it’s strange and unsatisfying, and the whole third act operates as a kind of short story that requires a novel’s worth of setup. It turns out that Casino Royale is also weird like From Russia, at the level of structure.

That doesn’t stop it from being weird in its political and social attitudes, too. Le Chiffre’s role as an agent of international communism is treasurer of a union. Examining the face of one of his murderous henchmen, Bond concludes that it is not greed or sadism that motivates him to kill, but drugs: marihuana. Like Bond’s attitude toward women, these details sound to the modern reader like a parody of the early fifties. Here’s a three-part question: How much do Bond’s ideas about women and unions reflect the attitudes of the author? How much are we willing to forgive these attitudes as a product of Fleming’s era? And to what degree was Fleming in step with the ideas of that era, i.e. how much of this “unions = communism” business is the especially conservative thinking of a wealthy man who worked for British intelligence as the Cold War was taking shape?

The number of variables at play makes these questions unanswerable. If you read as an expression of your ethics, you probably shouldn’t read any Bond novels at all. If you are willing to read for aesthetics, though, Casino Royale is worth it. Despite its weird, unbalanced structure, it is paced extremely well. At no point was I bored. Even having seen the 2006 movie—which diverges substantially from the original but still hits most of the same beats—the twists were exciting to me. The great strength of this novel, I think, is Fleming’s willingness to treat his hero roughly. Some early surprises convince the reader that Bond is not guaranteed to win, creating such a sense of menace that by the third act, mundane events like the appearance of a man with an eyepatch become sources of suspense. Despite its many faults, Casino Royale possesses the page-turning quality that most contemporary literature conspicuously lacks.

I’ve read a lot of genre fiction in the last year, and this difference from literature has been the most revelatory. We think of literature as insisting on higher quality in all aesthetic categories. In my opinion, though, literature in the 21st century insists on higher-quality tone, imagery, and characterization, while accepting inferior pacing and plot. Contemporary literature is almost supposed to be boring. When I was younger, I accepted the superiority of literature to genre fiction without question, but now I wonder. In its decadent second century, natural realism might be as mannered and clumsy as any spy novel. Consider this sentence from Cormac McCarthy’s The Crossing, helpfully excerpted by B.R. Meyers in his critique of contemporary literature, A Reader’s Manifesto:

He ate the last of the eggs and wiped the plate with the tortilla and ate the tortilla and drank the last of the coffee and wiped his mouth and looked up and thanked her.

What distinguishes this sentence from pulp boilerplate except for the affected style? I like McCarthy a lot, and there are hundreds of sentences in his work that are better than anything Fleming ever produced. The literary tone is as stilted as the hardboiled, though, and its presence as a generic convention does not excuse the absence of pacing or plot. All this is to say that the modern reader should not understand genre fiction as inferior to literature, or rather that we should understand literature as another genre. What is lacking in one can abound in the other.

I’m reading 50 books in 2018. Casino Royale was number nine. Next, we’re reading Amarillo Slim in a World Full of Fat People.

“literature in the 21st century insists on higher-quality tone, imagery, and characterization, while accepting inferior pacing and plot”

Agreed, but in spite of your post and general good taste I can’t imagine reading this. I sat through Bond films at a time because Chris and Jamal got obsessed with them. It wasn’t just the misogyny etc that was weird. The plots were fucking bizarre and poor and boring, unless something exploded. I’d settle for “literary” McCarthy anytime. So thanks for your post, as always, but I hesitate to give this one a go.

5eh4vqf

gou4k1

uwfyws

9yxy4n