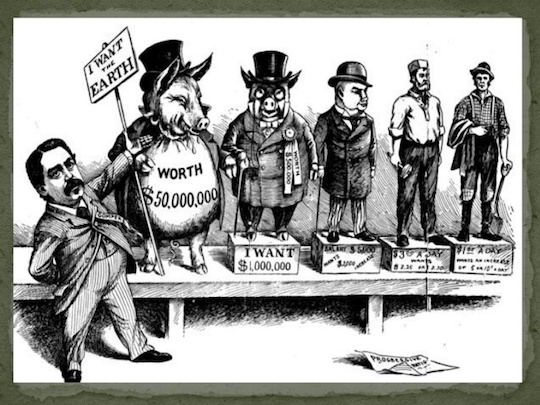

The big historical misconception of the Gilded Age is that it was an age of great wealth, when really it was an age of widespread poverty. Between 1870 and 1900, growing industrialization and the sudden interconnection of markets by rail made a small number of American industrialists insanely rich. The Gilded Age produced the Rockefeller, Vanderbilt, and Carnegie fortunes. It also impoverished millions of ordinary Americans, who went from self-employment as small farmers and independent craftsmen to working in mills and on railroads—often for sprawling trusts, usually with little control over hours or conditions, and invariably for low wages in an economy driven by industrial-strength inflation. The Gilded Age made a few people rich at the expense of everyone else. It is named for the 1873 novel by Mark Twain, and the whole point of “gilded” is that the gold only covered the surface. Beneath it lay something base that the wealthy wanted to cover up. Anyway, I don’t know why I’m thinking about this in the 21st century, during our second industrial revolution. I guess I’m just savoring the fact that nothing like that could happen now. Today is Friday, and our age remains totally un-gilded. Won’t you insist that everything is fine with me?

Tag Archives: profile

Why isn’t Trump comedy funnier?

When President Trump praised the non-existent country of Nambia at the UN in September, Bill Maher joked that the capital of Nambia was Covfefe. So did a seemingly endless number of Twitter users, not just over time but on the very same day. There is something about Donald Trump that encourages everyone to come up with the same jokes. There is also something about him that makes us feel the pressing need for political comedy. When a self-aggrandizing billionaire with an unusual physical appearance becomes president, satire should shine. Yet political comedy in the first year of the Trump administration has been strangely lackluster. Why isn’t the most comical president in history generating better comedy?

The New York Times Magazine let me consider this problem in a profile of Anthony Atamanuik, who plays Trump on The President Show on Comedy Central. Gigantic, sun-blotting props to Willy for helping to develop a unified theory of Trump comedy, which starts like this:

A funny Trump impression presents two broad challenges. The first is that the president exists in a cloud of signifiers: his infomercial hand gestures, his practiced facial expressions, his broad accent and narrow diction and relentless catchphrases, to say nothing of his hair and skin. Any impression of him must include these signifiers, but they are so numerous and recognizable as to weigh it down, limiting the space for the impressionist to contribute his own insights. The adage “It’s funny because it’s true” is a phenomenological account. It describes a change in the audience: It’s funny because (I just realized) it’s true. We laugh when we are surprised to recognize something. The problem with Trump is that everything about him is recognizable immediately. There seem to be no subtle truths under the cacophony of overt signifiers, so that every joke about him becomes merely a reference.

That’s the Covfefe Problem: It’s hard to think of an original joke about Trump, but it’s easy to think of a recognizable reference. The other horn in this comedy dilemma is the Clapter Problem. What is clapter? You’re just going to have to read the profile and find out, or buy Mike Sacks’s book Poking a Dead Frog, which is where I first encountered the term. But while you’re waiting for the book to arrive, read the Times piece. Remember how Combat! blog was on hiatus for weeks and everyone stopped reading it? This was one of the four big projects that forced me to put the blog aside. Now all of them are done, and I am rich. We’ll be back tomorrow with more self-promotion.