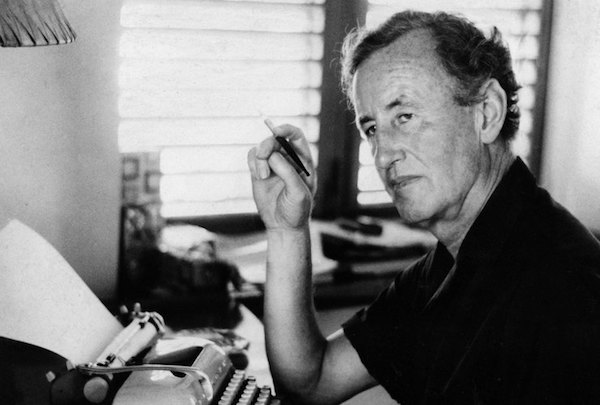

I read my first James Bond novel—From Russia, With Love—last Christmas, and I was surprised by how good it was. The prose captured a sense of anomie and moral ambiguity that is missing from the movies, and the plot moved along briskly. It was a yarn, and I wanted to read it when I wasn’t—the mark of a good genre novel. The Book Exchange here in Missoula sells used Bond paperbacks for $1.88 apiece, and I picked up three more when I got From Russia, With Love. Among them was Live and Let Die, which I finished yesterday. If I were going to recommend a Bond novel from the two I have read, I would go with From Russia, both because the prose is better and because I don’t want to develop a reputation. Live and Let Die is enjoyable, but only if you can get past the astonishing racism.

I guess we should all stop being astonished by racism, especially when we read books published in 1954. It’s fair to say that the exoticization of African Americans is not just an aspect but the central premise of Live and Let Die. The second novel in the 007 series, it is basically a crime/adventure story grafted onto the spy template. Tracing the source of ancient gold coins that have mysteriously appeared on the international market, Bond discovers the Harlem gangster Mr. Big, a genius endomorph who runs his criminal empire through a reputation for voodoo powers. One of the best parts of the novel is everyone’s agreement that voodoo isn’t real, right up until they get really scared and start to worry that it might be. Even Bond is not immune to this creeping terror, and it’s a great atmospheric effect.

To get to it, though, you have to wade through a lot of attitudes toward race that can charitably be described as “old-timey British.” The major set piece of the first act is America, and Fleming does not disguise his disdain for the diner food, clipped speech, and retirement communities of the USA. If America is a foreign country through the lens of Bond’s wry English chauvinism, Harlem is another planet. Every man is a superstitious hustler in peg-topped trousers, and the only (black) woman is a jazz sex witch. Mr. Big’s whole gang is black—Fleming scrupulously uses the word “negro,” which was polite at the time—and the key to his hold over them is their natural superstition. They have colorful names like Poxy and Tee-Hee, and they speak in the apostrophized dialect of southern sharecroppers, even though they live in New York. When Bond sneaks into Florida, he is made by a black cab driver who calls him in to Mr. Big’s operation. Almost every black person in this book is part of the same criminal underground.

I was curious whether Bond would get a black love interest, but the girl in Live and Let Die is a white daughter of Haitian planters named Solitaire. Mr. Big believes she has psychic powers, and he is determined to make her his wife. The adventure that ensues takes them to Florida and then Jamaica, with plenty of booby traps, voodoo curses, and carnivorous fish along the way. Bond and his friends are in danger an impressively high percentage of the time, which keeps the pages turning. In order to enjoy the story, though, you have to overlook the author’s presentation of black people as a type—some good, some bad, but all as exotic as the barracudas and tropical islands that compose the rest of the mise en scene.

I could do that, because I like genre fiction and enjoy looking past the details to the mechanics underneath. Also, I’m white. It’s easy for me to forgive Fleming his “don’ choo move, Mistah Bond” and monologues about how black people are superstitious because they grew up without education in an atmosphere of terror. That’s just an unfortunate aspect of the past, and I condemn it in roughly the same way I condemn its contemporary manifestations, i.e. comfortably, from a place they do not reach. If I were black, Live and Let Die would probably not be a charming adventure story with problematic features, but rather another example of how most books in English were written on the presumption that I would not read them.

The sixty-five-dollar question is what we do with books like that now. We can throw Live and Let Die on the fire and read some China Mieville instead, but are we prepared to do the same with Othello? That’s a work by a well-meaning author that’s astonishingly racist by contemporary standards, too; it’s just better, probably, than a Bond novel. The easy solution is to approach racism in old books like the word “shan’t”—something that jangles the modern ear but was ultimately just a feature of the time. This calculus breaks down, however, when we ask why we’re excusing it. Was the racism of the 1830s any less bad because everyone bought into it?

These questions do not have simple answers, but I do think it’s possible to read Live and Let Die in spite of the racism, without endorsing it. I listen to a lot of Future, but I don’t endorse prescription drugs and cynical materialism. Those elements are part of a larger, ambiguous whole. I’d be willing to split hairs so finely as to say it’s not Future that I endorse so much as the act of listening to Future. Maybe this is sophistry, though, and we’re only trying to gloss over the sins of someone we like. If you haven’t read any Bond books, check out From Russia, With Love. I’m glad I read Live and Let Die, but the baggage may not be worth the trip.

I’m reading 50 Books in 2018; Live and Let Die was number seven. Next, we’re reading The 20 Days of Turin by Georgio De Maria.