Peter Daou first came to my attention via Twitter, where he is routinely mocked by snarky journalists. A former advisor to Hillary Clinton and John Kerry, Daou is now a commentator and activist who founded the group/hashtag #HillaryMen. He is also a former member of the Lebanese Forces, a Christian militia organized during the Lebanese civil war. In a post on his personal blog this morning, Daou announced his intention to sue for defamation various unnamed Twitter users who have accused him of complicity in the Sabra and Shatila massacre of 1982. Daou describes his war experience as extremely traumatic, saying that he never killed anyone and was conscripted against his will. He has publicly condemned the Sabra and Shatila massacre and contends that tweets related to it were meant to defame him in retaliation for his support for Hillary. The big question, in this brave age of social media, is whether tweets can constitute defamation in the same way as broadcasts and publications from media outlets. Daou thinks so, but his case is complicated. Examples after the jump.

Daou doesn’t specify which tweets he will cite in his planned defamation suit. It’s reasonable to think at least some of them have been deleted, but it’s hard to know. A search of “Daou Sabra” turns up these three:

That seems pretty nasty, especially when directed at a man who wrote this about his experience:

In all my time in Lebanon, I never harmed a soul. But I learned the horrors of war up close and personal and it shaped the person I am today. I have survived intact by owning it all, by accepting everything I went through as a trial by fire, in the most literal sense of that phrase. It was an awakening to the cruelest aspects of human nature. Coping with war is not easy and I’m eternally thankful that I’ve been able to build a successful life and career despite growing up in a living hell.

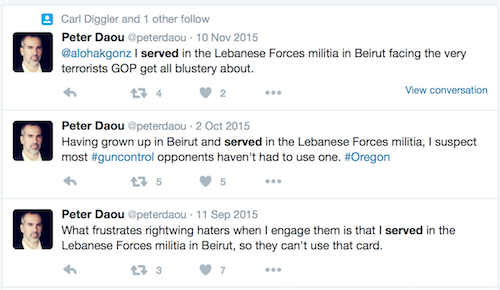

Clearly, Daou did not like being in the Lebanese Forces. This passage characterizes his experience as something awful that happened to him, as does the use of words like “conscripted” and “mandatory” in his post. This characterization contrasts with some of his earlier tweets, however, in which he describes his war experience as service:

The ideas of Daou as an unwilling teenage conscript and as a serviceman facing terrorists are not necessarily exclusive, but they strike different tones. This contrast, in context of his support for Clinton’s relatively hawkish foreign policy platform,1 seems to be the basis for twitter users’ remarks.

But are those remarks defamatory? They certainly seem to be untrue. Daou denies being involved with Sabra and Shatila, and no evidence suggests he was. It may be unseemly for a man so traumatized by his own experience with war to support US military intervention abroad, but it doesn’t justify implying that he massacred civilians. If someone wrote that kind of thing in a newspaper, it would be libel.

But newspapers circulate to thousands of people. Twitter user @tybuddhaboy, above, has 126 followers, most of whom would not have seen his tweet directed to another user. Libel laws don’t make distinctions based on the audience of the defamatory statement, but before searchable social media on the internet, they didn’t have to. A libelous note to a friend or sign at a party would probably never be seen by the person libeled.

But on the internet, you can search your name—especially when you’re concerned people are saying untrue things about you. The question is not whether connecting Daou to a war crime is defamatory; it almost certainly is. The question is whether a dude with 126 followers can damage Daou with a tweet in the same way that a publisher or broadcaster can.

I’m not an attorney, and maybe that question is orthogonal to Daou’s (forthcoming) lawsuit. But it seems relevant aesthetically, if not ethically. It’s easy to see why this is a sensitive issue for him. But we all expose ourselves to awful, stupid comments when we participate in social media, and ignoring them seems to be essential to modern living. Daou’s lawsuit draws attention to a new feature of our time: it’s much easier to libel and be libeled. But there is a difference in degree of speech at work here, and it may be just as important as differences of kind.

I don’t know much about defamation law, so this may not be accurate, but my guess is that the size of the audience relates to the size of the monetary award he could get as damages for the comments, but would not be relevant to whether or not something is considered libel in the first instance.

To your point, part of the reason this likely never came up before is that no-one was going to spend a bunch of money on legal fees to go after a political zine with a circulation of 73 (possible title: “The Dread Scott”). It would seem like Daou either has intends to go after Twitter itself or is a fighting on principle.

To follow Mike S: …. or he’s just looking for attention or likes to feel wronged. These are not suits for money.

This all kind of makes me never want to go into Twitter, which is the same feeling I get on those rare occasions that I go into Twitter.

Defamation is the general category of communication involving false statements that intentionally or negligently causes damage to the subject of the statement. The subcategories are libel and slander. Libel is generally the written word; slander is generally the spoken word. So, all libelous statements are defamatory, but not all defamatory statements are libelous.

The real issue IMO is the law of the forum. Every states has different laws regarding defamation. These laws relate to how such claims are proven (e.g., who has the burden of showing the statements are false) and establishing damages. Don’t quote me on this, but I believe the location of the tweeter would control. Interesting, if not exciting, questions of law abound.

Thanks for clearing that up, Mike and Jason. It’s a good thing some real damn lawyers read this blog. As you probably know already, courts have found that internet platforms generally can’t be held liable for the defamatory statements of their users, per Sec. 230 of the Communications Decency Act (1996.) So Daou can’t sue Twitter. The scale-of-damages argument makes sense. It seems like it’s personal for him, and he wants to make an example of the guy who writes Carl Diggler.

He could be invoking the Streisand effect to bring attention to himself. Or unintentionally invoking it and bringing attention to the claims he sees as slander. I, for one, only know one thing about P.Daou, which is one thing more than I knew about him before this post–people say he massacred people.

But they’re almost certainly lying! Don’t sue me, Peter Daou.