A. Ron Galbraith recently brought to my attention this post in Politico arguing that The Daily Currant is not funny. You may have heard of The Daily Currant in connection with this mistake by the Drudge Report, or possibly this one by the Washington Post. According to founder and editor Daniel Barkeley, the Currant produces a “style of satire [that] is as old as literature itself, but hasn’t recently been applied to news articles.” Apparently one of the satirical conceits over at the Currant is that The Onion doesn’t exist, but that is orthogonal to our discussion. Barkeley’s position is that several of the Currant’s satires have been mistaken for news because what he’s doing is so new. At Politco, Dylan Byers’s argument is that Currant articles keep being taken for real because they aren’t funny. Which brings us to an important question: how funny does satire have to be?

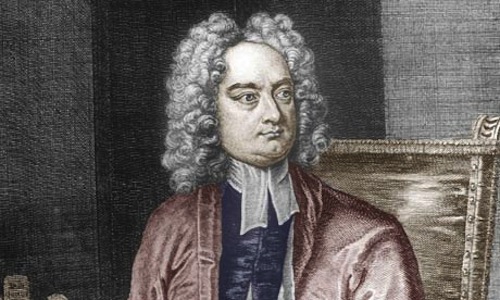

I submit that historically, satire is the Bruce Springsteen ballad of humor. Because it addresses itself to social issues, it is under less pressure to rock (i.e. make people laugh) than other subgenres of humor. That is perhaps also why satire makes it into the canon of literature much more easily than other comic writing. Everybody read “A Modest Proposal” in high school, and it’s not because Swift was so funny that he stuck separate wigs to each side of his head when he went bald. It’s because he was writing about a famine in Ireland.

Satire addresses social issues, in other words. The narrative may be absurd, but the premise—the underlying element that enables us to get it—is always located in real life. You couldn’t write a satire about the social hypocrisies of Saturn colonists, unless those social hypocrisies strongly resembled our own. So it is definitionally necessary that satire find its subject in the real.

Yet that is not sufficient. An essay about how Bashar al-Assad is abusing the people of Syria is not satire, because it’s not funny. Mere sarcasm—saying, “boy, Newt Gingrich sure has his finger on the pulse of youth culture,”—is not satire, because it isn’t funny enough. Here we encounter the problem with The Daily Currant and Barkeley’s claim:

As stated in our about page, we don’t focus on headlines or one-liner jokes. Our humor is character-driven and found in the narrative structure of our stories. (Though most articles also have clearly identifiable jokes, they don’t take up the whole piece.)

It’s interesting that Barkeley would use the phrase “character-driven,” since articles in The Daily Currant are almost invariably about real people. The narratives generally take a famous person and have them do something in keeping with their character, such as Bachman Threatens to Leave Minnesota Over Marriage Equality. See, Bachmann is against gay marriage, and so for her to leave Minnesota would be…in keeping with that. It’s like the incongruity theory of humor, only it makes use of congruity to achieve [Ed.: the rest of this sentence is opinion] absence of humor.

Sometimes the narrative of a Daily Currant satire turns on someone simply being wrong, as in Blackberry CEO Says Android ‘Not a Serious Threat.’ This approach conforms better to the incongruity theory, but in a way that reveals its limits. It’s not funny merely to say something that isn’t true, and it is not satire to point out a truth by declaring its opposite. These approaches take the form of satire while missing one of its essential functions: satire says something untrue that draws attention to an unsaid truth.

That’s why the Blackberry CEO thing isn’t funny. Everybody knows that Android has a bigger market share than Blackberry, and so the article draws attention to a truth that is recognizable but not surprising. Compare that to an article from The Onion that Barkeley said “clearly does not have a deeper message,” ‘Fuck You,’ Obama Says In Hilarious Correspondents’ Dinner Speech.

The joke here is not simply that the President wouldn’t use profanity in such a speech. It’s that his anodyne speeches belie a real animosity between himself and the press, and that the fictional version of that press is still reporting his angry diatribe as “hilarious.” This premise points out a recognizable truth that goes unacknowledged, unlike the widely acknowledged truths that Bachmann hates gay marriage and Android is beating Blackberry.

So we wound up determining how truthful satire has to be, and not how funny as we set out to do. I think, though, that the two questions are closely related, and The Daily Currant is bad satire not so much because it isn’t funny, but for the same reason that it isn’t funny. It takes for its premises obvious truths rather than revealed ones. It’s the difference between “take my wife—please” and “I do not love my wife, so take her.” I suspect that’s why its satires are so often mistaken for news. They trade in ideas that we are already used to seeing, so that the whole production is not incongruous so much as inaccurate.

Yeah, the Daily Currant authors run into a problem when they have to write a second sentence following up on the celebrity-gag headline. Sarcasm is the poor-man’s irony, after all. Cheap fuel, burns quick, but doesn’t take you very far. The Onion and Colbert have a Swiftian style and imagination, but Currant reads like a transcript of a vocal impression that was funny if you were there?

Question: does The Daily Show count as satire anymore?

Satire can be based on an true, revealed premise, but taken to an absurd extreme rather than a logical outcome. E.g.: “Chris Christie eats a whole chicken” vs “Chris Christie devours a schoolbus full of children.” Both derive from the premise that Chris Christie has been known to overeat.

Michelle Bachmann is already absurdly crazy, so in order to satirize her using premises that are ostensibly true, the satirical outcome would have to have been taken much farther than the Daily Currant did. A headline like “Michelle Bachman threatens to return to her home planet over marriage equality” or “Michelle Bachmann threatens to sacrifice an ox to summon Asmodai, seven-membered lord of lust and debauchery over marriage equality” would probably be funnier.

Michelle Bachmann is satire. If you wanted to mock heartland ideology, she is the character you might create to do so. Therefore any satire of her, if we’re going to pretend she’s a real person, would rely on this premise.

“Michelle Bachmann collapses due to exhaustion outside of Family Values Rally: ‘I have a degree in law, for godsakes, you know how hard this is?’ She was promptly helped back to her feet by her husband. Wiping a cold towel across her forehead, she stepped to the podium and resumed her speech. “Okay, where was I? Right, marriage equality denies Christians their god-given and constitutionally protected freedom…”

I could plausibly get a job at the Daily Currant.