Secretary of State John Kerry argued Sunday that Russia was heavily involved in the downing of a Malaysia Airlines 777 over eastern Ukraine, and he did it in the most tepid way imaginable. Before we go any further, let’s take a moment to consider what an insanely awful thing happened Thursday. Someone used a military anti-aircraft missile to shoot down a commercial airliner carrying almost 300 people, either accidentally or because they could. Probably, it was the second one. Regardless of how you feel about the conflict in Ukraine, it has enabled at least one crew of surface-to-air missile operators to kill 300 civilians for sport. According to the US State Department, that’s Russia’s fault. And Secretary Kerry is here to tell the world, in roughly the same tone as stereo instructions.

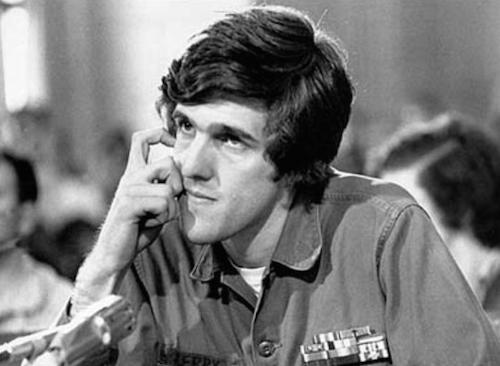

Here he is on CNN’s confusingly named “State of the Union”:

We know for certain that the separatists have a proficiency that they’ve gained by training from Russians as to how to use these sophisticated SA-11 systems.

We’ve talked a lot about nominalization in our Close Readings lately, possibly because it’s a cancer on contemporary rhetoric. As you all remember from your notes, to nominalize is to shift the meaning of a sentence from verbs to nouns—or, if you prefer, nominalization is the shifting of meaning in a sentence et cetera etc. What I’m going to call first-degree nominalization relies on the verb “to be.” But if you really want to nominalize like a pro and evacuate all visceral impact from your sentences, you’ll probably want to go second-degree and make everything “to have.”

Kerry is a pro. His job requires him essentially to blame Russia for the downing of MA Flight 17, but it also requires him not to enrage Vladimir Putin. These are conflicting goals. Pretty much nothing Kerry could say would both hold Russia responsible and not anger Putin, because Kerry is accusing him of a horrible thing. And so, tempered in the fire of several losing campaigns for President, the Secretary garbles his own message.

Here’s Kerry’s statement de-nominalized, with the object of his accusation as the subject of the sentence:

We know for certain that Russians trained the separatists to use these sophisticated SA-11 systems.

Pretty clear, right? Short of saying that Russia also gave the separatists those systems, which it almost certainly did, Kerry could not cast blame more directly. Therein lies the problem. The sentence is too dynamic, establishing a chain of culpability that moves from Russia to the separatists to an SA-11 battery to 300 dead people. What Kerry wants is a bunch of clauses suspended in amber. So instead of Russians training separatists, “proficiency” becomes a thing that separatists have, acquired through training, itself not a verb but a gerund “from” Russians that relates to using antiaircraft weapons.

Hearing that sentence aloud encourages your brain to hibernate. Instead of transitive verbs that act on objects, Kerry gives us qualities possessed by people, including the bloodless phrase “training from Russians as to how to use.” The act of teaching someone how to shoot down a foreign passenger jet becomes the quality, “proficiency,” of knowing how to do that. This quality is one that the separatists “gained,” in much the same manner as a physical object, by training.

Not training as a verb, though—the preposition “from” doesn’t naturally go with verbs. “This is my jiu jitsu instructor,” people don’t say. “I train from him.” With this subtle violation of English diction, Kerry breaks the last connection between “Russia,” “training,” and “separatists.” Training is not some action Russians do to separatists; it’s something separatists have that they got from Russians, and it pertains to blowing up a plane and killing 300 innocent people.

Thus does one of the most horrifying acts of contemporary geopolitics become a series of inert qualities connected by variations on “to have.” Kerry set out to say that separatists would never have blown MA 17 out of the sky if Russia hadn’t taught them how to use surface-to-air missiles, but he found a way to say it that minimizes responsibility for all parties involved. That’s a mistake, because responsibility is his central message. Nominalization separates agents from their acts, people from what they do. It is exactly the wrong strategy for what Kerry wanted to say, unless he really wanted to say nothing.

This is good work.