In workshop, we used to say “that’s not a story; that’s a situation.” It was shorthand for a common problem: stories that steadily intensify a set of conditions, until everything comes to a head. Usually these conditions were pleasing and interesting, featuring characters with mutually exclusive desires, natural dialogue, evocative settings. They were deftly rendered situations, but the pleasure of a story does not abide in situations. Narrative aesthetics operate in the relationships among situations, the progression from one to another. A situation is in place, but then something happens, so another thing happens that changes the situation forever.

A situation is the great strength of The Twenty Days of Turin, which most every review describes as “the Italian cult novel.” The incident De Maria imagines—a three-week period during which an epidemic of insomnia drives the residents of his hometown into the streets, where they are mysteriously and vigorously murdered—is uncanny and haunting. It creates an effect of not horror but terror, the fear of a mastering logic we cannot grasp.

The visceral pleasure of this sensation is complemented by the drier satisfaction of parsing two analogies. The first is to the domestic terrorist attacks that frayed the fabric of Italian society in the 1970s. I don’t know much about the history of Italy after Mussolini, but just knowing there were widespread attacks and the government clamped down is enough to appreciate the symbolism. The monsters in this horror story use the people of Turin as weapons against one another, not metaphorically but physically. It’s a touch of pulp gore that is nicely balanced by its political subtext, creating a high-low appeal similar to a Lichtenstein painting. The second intellectual pleasure of this novel comes from The Library, the weird conspiracy that drives the insomnia epidemic and happens to be a robust parody of social media, 35 years before social media was invented. It’s like if Shakespeare had included a machine gun and a trench-based war with massive casualties in Hamlet.

The terror, the analogies to Italian troubles and social media, and the elaboration of De Maria’s golden premise are all great. The problem is that while we learn more about this situation as we read on, it doesn’t change. It just gets fleshed out. The appeal of this novel is the world, not what happens in it.

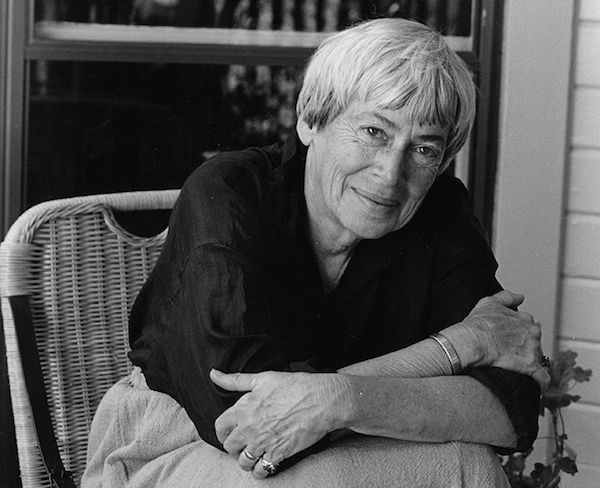

This problem is endemic to speculative fiction, by which I mean the genres formerly called science fiction, fantasy, and horror. The classy reviews of The Twenty Days of Turin have called it magical realism, but it’s a horror novel. Supernatural forces kill people as the narrator tries to figure out what’s happening. He never really does, though, which obviates the ending to the horror story in which the heroes try to stop what’s going on. This story is about the situation during the twenty days, not one man’s struggle to address it. De Maria is not interested in his hero except as the flashlight on his spooky tour of Turin, so he uses a method for turning situations into stories established by Jorge Louis Borges. He tells the story of the protagonist researching the situation.

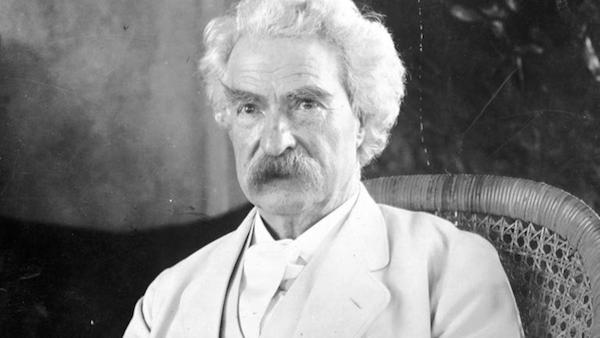

Borges’s story Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius is an exemplar of this approach. The big idea is a land whose inhabitants deny the reality of the world. Borges has lots of fun exploring this idea, including positing a language without nouns, but such conditions make it hard to think of what happens in act three. To get around this problem, he builds a narrative framework from the process of the first-person narrator finding out about this world. His friend remembers reading about Tlön in an encyclopedia, but then it’s not there, so they go looking for it and find a conspiracy to cover it up.

The beauty of this structure is that it allows Borges to substitute pacing—the gradual revelation of interesting details about this world—for plot. The story becomes the change in the protagonist’s awareness of the situation. That’s a thin story, but it holds our attention because we love finding out about this world, too, and we empathize with the protagonist’s curiosity. This solution to the situation-not-a-story problem works particularly well for horror, in which so many aesthetic effects are achieved by withholding information to give shape to the unknown.

That’s why The Twenty Days of Turin works, in my opinion. The story is set a decade after the twenty days, when the protagonist pursues various lines of inquiry about them and encounters mysterious resistance. From the beginning you feel like something creepy is going on, and the morsels of information you get about it only sharpen your appetite. This approach solves the problem of situation and not story, but only temporarily. It erupts again at the end, when the protagonist’s investigation must conclude. The conclusion can’t be him finding out everything there is to know; that kills the horror effect, like when you see the whole alien at the end of Alien and it’s a guy in a rubber suit. So De Maria goes with another ending that feels decisive but also tacked on, a violation of the aesthetic principles that have guided the book so far.

I am better at situations than stories. I think most writers are. The advantage of pacing the story by changing the situation, however, rather than parceling out ever more interesting details, is that it makes the ending easier. When every step takes you closer to the finish line, crossing it is easy. I feel like De Maria reached the last twenty pages of this novel when he was too far from the line, and he had to take an ungainly leap across it. It’s a beautiful day at the track, though. The world of this novel is worth it, even when the story is not.

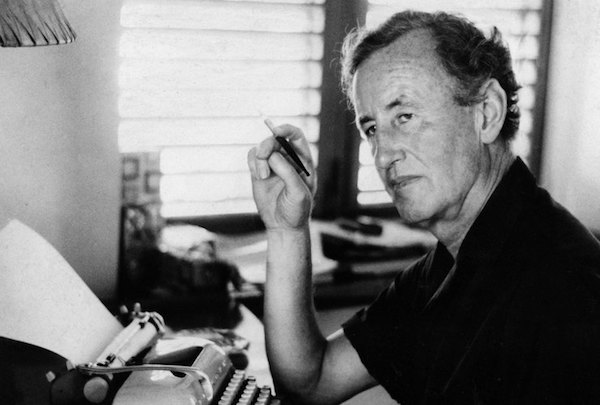

I’m reading 50 books in 2018, and The Twenty Days of Turin was number eight. Next I’m reading Casino Royale by Ian Fleming, but that’s kind of a lie because I finished it while I was in Denmark. We’ll talk about it tomorrow. If you want to read along in real time, gazing up at the moon and wondering if I’m looking at it, too, I’m reading Amarillo Slim in a World Full of Fat People now.