God damn it, I love wizard shit. When I was a child I read approximately ten Bibles’ worth of TSR-branded novels, all containing heavy doses of wizard shit. From there I read the Robert Aspirin run of Myth, Inc. books—comic novels about a boy who learns magic from a demon and uses it to run a private detective agency.1 I read the Xanth novels, which I remember not at all because I was eleven but now understand to have been infamously sexist. I didn’t notice that part, because I was focused on the wizard shit. I would probably read Mein Kampf, if you told me there was a wizard in it. The only wizard shit I don’t like is Harry Potter, for reasons that I hope to gently make clear to you as our discussion progresses.

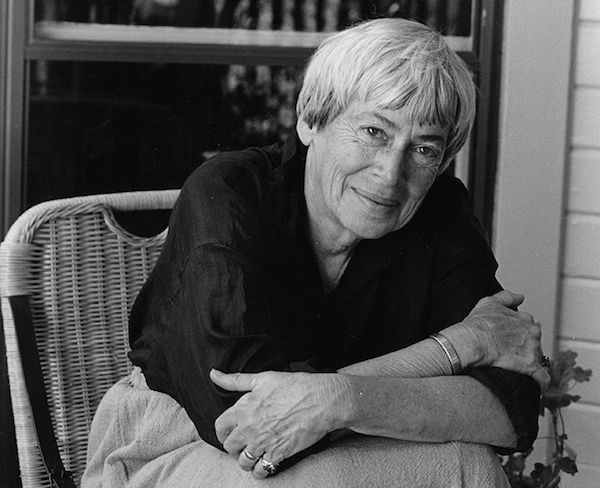

In order to demonstrate my goodwill toward you and your personal choice of wizard shit, which is not a matter of right or wrong but only of aesthetic preference, I will recommend you a book. If you liked Harry Potter, you should check out A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula Le Guin. It’s about a boy from an island village who learns he has great aptitude for magic, so he goes away to wizard school. I know that doesn’t sound like anything Harry Potter fans would like, but hear me out. There are some similarities between Le Guin’s novel, first published in 1968 and in print continuously since then, and J.K. Rowling’s 1997 smash. For example, in both novels, magic is accomplished by saying particular words.

Everything in the world of A Wizard of Earthsea,2 has a “true name” in an archaic tongue, and these names can be incorporated into incantations in that language to cast spells. People go by public names and keep their true names secret, since telling someone your true name gives them the power to cast spells on you. The revelation of one’s true name is therefore a gesture of profound trust. Also, it’s hard to memorize all these words, and the learning of magic is understood to affect the student’s mind. This is especially the case for Ged, the protagonist, who is impetuous and suffers multiple blows to his psyche as a result of magic gone awry.

Anyway, Le Guin does a great job of establishing two things right off the bat: magic is hard, and magic makes you weird. These two operating principles are, in my opinion, essential to the magic novel, a genre whose premise—anything can happen!—is opposed to the fundamental principle of narrative storytelling. The world of the story must be consistent. That’s especially true for speculative fiction, a genre that is often said to live or die on world-building. No one wants to read a story where stuff happens arbitrarily. A good magic story is not about a world where anything can happen; it’s about a world where magic can happen.

In order for events to matter in a world where magic happens, we have to believe there is a system behind the magic. This system has to be mysterious, therefore limited by what is known of it, and complicated, therefore limited by what that a given wizard can learn of it. These limitations are what keep magic from functioning as a deus ex machina. They tell us that, okay, magic will do some amazing things in this story, but it’s not going to solve every problem. Even in this world of miracles, there are going to be consequences, and those consequences will be irrevocable—the essence of a good story.

A good book about wizard shit shows us the limitations of magic by demonstrating that it’s hard to learn, and the learning process makes wizards weird. Early on, Le Guin shows us that magic will mess Ged up. He’ll pay a price for all this forthcoming wizard shit. Ged suffers injury early on, but he also suffers psychic wounds and unwanted changes in perspective. In A Wizard of Earthsea, practitioners of magic are known to become more committed to “balance” as they advance—a vague idea of equilibrium that seems to abandon any firm commitments to the details of the world, even the idea of good versus evil. Such changes—changes to ourselves, our values—are the ones we fear most. For the reader, the knowledge that magic will change Ged and possibly destroy him adds tension to a story that might otherwise be summarized as “lucky boy in the world of whatever we say.”

Which brings us back to Harry Potter. I don’t care for Rowling’s style, so that’s part of the problem. But the main reason I didn’t care for the first Harry Potter book3 is that the system of doing magic was not a arcane language of incantations that took weeks to memorize and pushed wizards into neurasthenia as a defense against madness. It was Latin. Or like, whimsical variations on latinate words. Harry waves his wand and says “luminem onnum!” and the lights come on. Doing that doesn’t make him crazy or unable to love for a few days or anything. He just does it and reveals the natural talent he always was. One gets the sense that magic in this world will be something Harry gets in this story, rather than something he pays for with his own humanity. Magic lifts too many constraints from Harry Potter without adding them back in somewhere else, and with too few constraints the flow of a story stagnates.

Anyway, I like wizard shit because it’s one of those genres that can be endlessly iterated, like vampires. Those stories aren’t about drinking blood. They’re about interesting variations on how the blood drinkers must live, and the gambits they might make to keep doing it. Le Guin creates s novel variation on how magic might work and makes it take a meaningful toll on Ged, even as he commits to it further. If you like wizard shit, or just stories about young prodigies who go to wizard school, you’ll love A Wizard of Earthsea. I’m afraid there is no comparable theme park.

I’m reading 50 books in 2018, and A Wizard of Earthsea was number four. Next I’m reading a longtime favorite, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek by Annie Dillard. Join me!