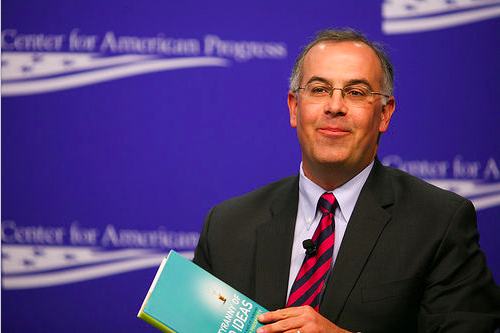

In a column he describes as “a great luscious orgy of optimism,” David Brooks suggests today that we all stop worrying about the state of American governance, political discourse, finance and world influence, because the country is going to be saved by—ready?—population growth. Props to alert reader/muay thai enthusiast Mike Sebba for the link. We’ve discussed the vexing phenomenon that is Mr. Brooks before (as well as the vexing phenomenon that is Mr. Brooks.) He’s either the most insightful commentator who’s still frequently wrong or the most frequently wrong commentator who still manages a lot of insights. Either way, it’s as hard to get on board with him as it is to jump off into the lake. If he weren’t a conservative, or if he were not so consistently juxtaposed with the mind-warpingly boring Thomas Friedman, we at Combat! blog probably wouldn’t be pulling for him so much. As it is, though, he’s like your friend with the stutter who wants to be a stand-up comedian: you hope the world will suddenly start to work in such a way as to make David Brooks right. Usually, that is. Today, David Brooks has written a column whose fundamental assumptions are so bafflingly stupid as to merit a big old Come On, Son.

Brooks begins by noting that, according to a recent poll, sixty percent of Americans believe that the country is headed in the wrong direction. The discovery that the majority of Americans now share the same attitude as your high school girlfriend who thought everything was bullshit is A) alarming and B) utterly unuseful, but Brooks takes heart in the projection that, by 2050, the United States population will have increased by 100 million. If present trends continue, 60 million of those new people will glower despairingly at you across the intersection while you wait to make complementary left turns into identical Starbuckses,* but Brooks thinks present trends are going to change. Sure, the last thirty years of population growth resulted in gross urban sprawl, but the next thirty years don’t have to be that way. Paraphrasing a book by Joel Kotke, Brooks predicts “an archipelago of vibrant suburban town centers, villages and urban cores.” So, um, suburban sprawl.

but Brooks thinks present trends are going to change. Sure, the last thirty years of population growth resulted in gross urban sprawl, but the next thirty years don’t have to be that way. Paraphrasing a book by Joel Kotke, Brooks predicts “an archipelago of vibrant suburban town centers, villages and urban cores.” So, um, suburban sprawl.

Lest we think Brooks is simply advocating Jersey without New York, he assures us that the island chains of the future will emphasize “meaningful places… suburban gathering spots where people can dine, work, go to the movies and enjoy public space.” He calls such developments “neo-downtowns,” and it just so happens that my home town—West Des Moines represent—built one a few years ago. It’s called the Jordan Creek Town Centre,*![]() and it’s a mall with a movie theater, a bike trail that leads to nowhere, and a P.F. Chang’s and a Joe’s Crab Shack in the parking lot. The “village” that surrounds it is a treeless expanse of big box stores and townhouses, containing everything offered by an urban downtown, provided you’re imagining a downtown without bars, performance venues, secondhand stores, art galleries, street vendors or public gathering places. Basically, it’s downtown Geneva, 1764. You can do anything there, from shopping to buying things to going to the store.

and it’s a mall with a movie theater, a bike trail that leads to nowhere, and a P.F. Chang’s and a Joe’s Crab Shack in the parking lot. The “village” that surrounds it is a treeless expanse of big box stores and townhouses, containing everything offered by an urban downtown, provided you’re imagining a downtown without bars, performance venues, secondhand stores, art galleries, street vendors or public gathering places. Basically, it’s downtown Geneva, 1764. You can do anything there, from shopping to buying things to going to the store.

Brooks has always taken an economist’s view of America, and economists tend to imagine people in units of four, each competing with the others to buy a larger house. The consumer culture implicit in his vision of 2050 America isn’t limited to geography. Remember that fiscal collapse he mentioned in the first paragraph? Our bigger, younger, more dynamic population will straighten that out by 2050, too, because “demand will rise for the sorts of products Americans are great at providing — emotional experiences.” Brooks argues that the United States will become an economic superpower again by producing things like The Wire and Mad Men, and by creating “companies like Apple, with identities coated in moral and psychological meaning, which affluent consumers crave.” Yes, coated in not just one but two flavors of meaning: moral and psychological.* Brooks evidently imagines a 2050 in which the people of China have become sufficiently affluent as to support 400 million of us by buying Sopranos DVDs, but not so affluent that they start making their own TV.

Brooks evidently imagines a 2050 in which the people of China have become sufficiently affluent as to support 400 million of us by buying Sopranos DVDs, but not so affluent that they start making their own TV.

Brooks makes some good points about the promise of US investment in research and development, and the degree to which the productivity of the American worker exceeds that of her Chinese counterpart, whose feet are bound so tightly that she can barely get to the metal press. But he also foists on us a terribly misleading statistic—one that, coming from a man so quantitatively-minded, can only be ascribed to business-sector boosterism. And I quote:

As Stephen J. Rose points out in his book “Rebound: Why America Will Emerge Stronger From the Financial Crisis,” the number of Americans earning between $35,000 and $70,000 declined by 12 percent between 1980 and 2008. But that’s largely because the number earning over $105,000 increased by 14 percent.

Wow, right? It sounds as if a bunch of those $35-70k earners went right up into the $105k bracket, doesn’t it? Of course, only about 10% of Americans make over a hundred grand, whereas 57% make between $35k and $70k, so a 12% decrease in one outnumbers a 14% increase in the other by about five to one. The vast majority of Americans who were economically mobile in the last thirty years moved out of the middle class and into poverty. But hey, the number of millionaires is way up!

That sort of concentration of wealth—the kind that turns cities into angry husks and encourages people to move to antiseptic suburbs, and the kind that convinces 180 million Americans that we’re moving in the wrong direction—is the consequence of the new American economy Brooks praises. The United States has become a consumer culture, where wealth is the object of work rather than work’s consequence, and meaningful social interaction is increasingly replaced with shopping. When Brooks lauds “that moral materialism that creates meaning-rich products,” he says it as if the greatness of America lied in the strength of our brands. It doesn’t. A really light Mac laptop is no substitute for a dignified and intelligent political culture, any more than a Best Buy is a substitute for a town square. When Brooks says, “Relax, we’ll be fine,” I appreciate what he’s trying to do for me. I just don’t think he’s telling me the truth.

fuckouttaherewiththatbullshitson!

Kotkin – whose name is spelled with a “kin” at the end – is known as a bit of an apologist for suburbia among urban planning people: http://americancity.org/columns/entry/2092/

I read an advance of Richard Florida’s new book The Great Reset, and he is basically arguing for the same. It’s pretty depressing. But think of all the useless light-rail projects!

I disagree with the notion that “consumerism” is to blame for social ills. The evidence is overwhelming that people in wealthy, capitalist economies are happier, healthier, more civil, more peaceful, more tolerant, more environmentally conscious, and more interesting. GOVERNMENT is to blame for the loss of social capital. Doctors drive past accident scenes because they’re afraid of getting sued if they try to help and something goes wrong. Playgrounds are disappearing because Mommy can sue for millions if her snowflake gets a boo-boo. The “soul-less suburb” is largely a creation of the federal government’s mortgage-subsidizing programs, which favored only a few house designs and unnatural, all-residential neighborhoods. Without these programs, there would probably be more “cool” places to live—neighborhoods with a local pub or where you wouldn’t need a car to get around. Inflation caused by the Federal Reserve is the reason why people emphasize spending over saving.

GOVERNMENT is also to blame for rising inequality. When an economy is relatively free–when invidivuals are free to produce, consume, buy, and sell whatever they want, to whoever they want, at whatever price they want–ordinary people prosper. The more politicized an economy becomes–with taxes, tariffs, regulations, restrictions, licensing, subsidies, wealth redistribution, and bailouts–the more difficult it becomes for everyday people to get ahead. In American, inequality has increased as government power over the economy has expanded. The uber-regulated economies of Europe are even more stratified.

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2172rank.html

The CIA’s Gini index shows that countries with highly regulated economies (e.g. the Scandinavians) experience a high degree of economic equality. Meanwhile the United States is sandwiched between Uruguay and Cameroon, not exactly a great neighborhood, statistically speaking.

Wikipedia’s article on the Gini Coefficient features this chart

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Gini_since_WWII.svg

which shows that economic inequality in the United States has been rising steadily since the early 1980s, which was when Reagan era deregulation began to take effect.

Finding this information took me about 30 seconds thanks to the magic of the internet.

brilliant post today, and nice parsing of pappy brooks’ misleading stats

Fin: While I admire your commitment to a puddle-deep Weltanschauung, GOVERNMENT (!!!!!1/!) hasn’t mandated a litigious society. A prevailing aristocratic entitlement has.

The reason Mommy will sue if snowflake [funny] gets a boo-boo [more than what is needed] is because she feels she’s entitled to “economic justice” (whatever that means). That sense of entitlement is a not-so-distant cousin of people stampeding one another at the Toys ‘R Us at 7AM on Black Friday.